In my field of architecture, style and epoch are seen as fundamentally related. Would it be logical, then, to believe that a distinctive architectural style which emerged in Indonesia in the 1950s, and disappeared by the 1970s, was perhaps a response to the specific geopolitical influence of the postwar Independence era? Does such an identifiable style perhaps represent a veritable architectural transformation that came in tandem with the social and political “revolutions” of the time?

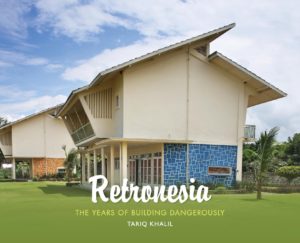

These are some of the questio ns that had prompted me to read Tariq Khalil’s Retronesia: The Years of Building Dangerously, a sophisticated architectural “coffee table book” that works more like a snapshot of a larger project to write a social history of an architectural style of Indonesia. In conventional architectural historiography, the era that spans the 1950s and 60s has been characterised by the modernism of Sukarno’s city-nation building. It is marked by a list of monuments and monumental architecture that paraded Jalan Thamrin and Jalan Sudirman, many of which were designed by Indonesia’s own artists and architects, such as Frederich Silaban, Sujudi Wiryoatmodjo, and Han Awal, among others. Architectural historians have also stretched a little bit back to the era of “revolution” (1945–1950), when Jakarta was occupied by the returning Dutch, to include the prestigious new town of Kebayoran. The ensemble of a set of new architectural styles in Kebayoran Baru, according to Soesilo, the Indonesian planner who played a leading role in the construction of the estate, was only fitting for its historical epoch.

ns that had prompted me to read Tariq Khalil’s Retronesia: The Years of Building Dangerously, a sophisticated architectural “coffee table book” that works more like a snapshot of a larger project to write a social history of an architectural style of Indonesia. In conventional architectural historiography, the era that spans the 1950s and 60s has been characterised by the modernism of Sukarno’s city-nation building. It is marked by a list of monuments and monumental architecture that paraded Jalan Thamrin and Jalan Sudirman, many of which were designed by Indonesia’s own artists and architects, such as Frederich Silaban, Sujudi Wiryoatmodjo, and Han Awal, among others. Architectural historians have also stretched a little bit back to the era of “revolution” (1945–1950), when Jakarta was occupied by the returning Dutch, to include the prestigious new town of Kebayoran. The ensemble of a set of new architectural styles in Kebayoran Baru, according to Soesilo, the Indonesian planner who played a leading role in the construction of the estate, was only fitting for its historical epoch.

What is significant about this era is that the architects or builders were typically not keen on traditional-style buildings. Their references to vernacular architecture were subsumed by modernist design, which stood up as the “spirit of the time”. Many of the architects (Dutch or Indonesians) were trained abroad, inspired by European design trends—especially modernism that developed in Northern Europe and—in the context of Khalil’s collection, America. If they were locals, whether they graduated from the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) or worked with and learned from the local Masters, they too were fascinated (terpesona) by new building materials especially concrete and prefabricated building blocks. Khalil’s book confirms all this general architectural history of the era, but he shows more. Many of the buildings he collects were by those whom we have never heard of, and a number of them have no records of who the builders were.

The book thus indicates, more than any architectural monograph endorsed by the profession, that architects were not dominant players in Indonesian building industries. Many of the houses and commercial buildings were designed and built by pemborong (contractors), artisans (craftsmen) and tukang (workers) who were well-trained to handle new materials, such as raw concrete. They also dared to design according to their taste, while quite self-conscious of what they were doing for their clients. They constituted a style that can be found discursively in many places in urban Indonesia, as Khalil discovered, but it didn’t lead into a major design firm, an association of certain dominant builders, or a certain architectural manifesto.

![]()

Tariq Khalil, a Scottish environmental consultant, takes on something of the ethos of a collector. He tirelessly exercised his connoisseurship, travelling across Indonesia, often on ojek and horses with a camera and notebooks to discover and document a wide range of building types: townhouses, villas, public buildings, ballrooms, churches, schools, universities, museums, hillside resorts, high styled villas, wisma (smaller, often family-owned, hotels), pharmacies (such as Apotik Sputnik), and stadia (such as that for Semen Gresik) associated with what came to be known as “arsitektur Jengki.” (Aside from Khalil’s book, the popularity of arsitektur Jengki has drawn the attentions of architects, academics and heritage communities who have published their accounts in various sources.)

Khalil started with buildings to later on discover the architect or the builder. As a result, he discovered many new names unknown to the architectural world of Indonesia. Of course, there were few architects, most prominent of whom was probably Gmelig Meyling (and Khalil shows a most fascinating photo of the firm’s construction crews—tukang—at a dining table), but most were builders, small contractors, engineers or architects who are new to us, such as Boen Sioej Tjoe (1954–1918), Boen Joek Sioe, Boen Kwet Kong (1912–1998), Sayogja, Harry Kwee, Oei Tjong An, Oei Tjong An, Yo Tjin Bok, Oei Kang Jan, Oen Poo Hauw, Siet Soen Fang.

The interesting thing about the list is that many of them are ethnic Chinese. Thanks to Khalil we now know that the architectural historiography of Indonesia from colonial to postcolonial eras would be incomplete without a serious consideration of building industries ran by the ethnic Chinese. As such Retronesia is the first to introduce unfamiliar names into the repertoire of Indonesian architectural history. It is also perhaps a first book about the architecture of the post-Independence era that seeks to capture a movement that spans across different cities and regions. It is also a first architectural book by a freelancer who, out of curiosity, discovers, documents and promotes what we can now call a “heritage building”. Most ambitiously, Khalil set up a mission for himself to search for a “national” architectural language in the style of the 1950s. This is not an easy task. While calling his collection “the architecture the 1950s style,” or “the Jengki,” he occasionally mentions the atmosphere of a different era, the revived Indisch and art deco style, the socialist realist expression, and the art nouveau. Such diverse stylistic references would be a contradiction for a quest for a single “national style.”

If influences in the architecture of the 1950s are hard to measure stylistically, then the the Jengki can be identified by the words used to describe its features: asymmetrical roofs and facades, playful shapes of doors and windows, tilted eaves and canopies, strong ornamentation, béton brut (raw concrete) material that goes against gravity. Together they compose a building that is at least eye-catching but almost always appear excessively loud—or nyorak. It is an architecture that speaks up, loudly, and it is meant for wandering cameras. It seems to be made for fun, or to be made fun of. It seems to carry no burden to follow the gravity of consensus. In any case, its expression is hard to describe, as it reminds Khalil of an object that resembles everything at once a “shop-house (which) at the same time an ocean liner.” It also reminds him of Asia, but once that leads him to America and then gado-gado before concluding that it is a “work of genius.”

The allusion to America has given the architecture its name: “arsitektur Jengki,” from the word “Yankee,” an informal term said to be used by some Britons and Australians to refer to people from the United States. But “Yankee” may have an Indonesian flavour: it might have derived from Dutch “Janke”, a diminutive of Jan. Khalil picked up the term from Frances Affandy, the executive director of the Bandung Heritage Society, who gave a talk about the “Jengki style”. Khalil was instantly fascinated by its “weird, strange, and playful” form.[i] And with the support of Affandy, he brought to himself a task to photo document the architecture across Indonesia. Surveying over twenty locations from cities and regions in different parts of Indonesia, the book shows diverse forms but together they seem to reinforce (as intended by Khalil) the stylistic unity of a national architectural style.

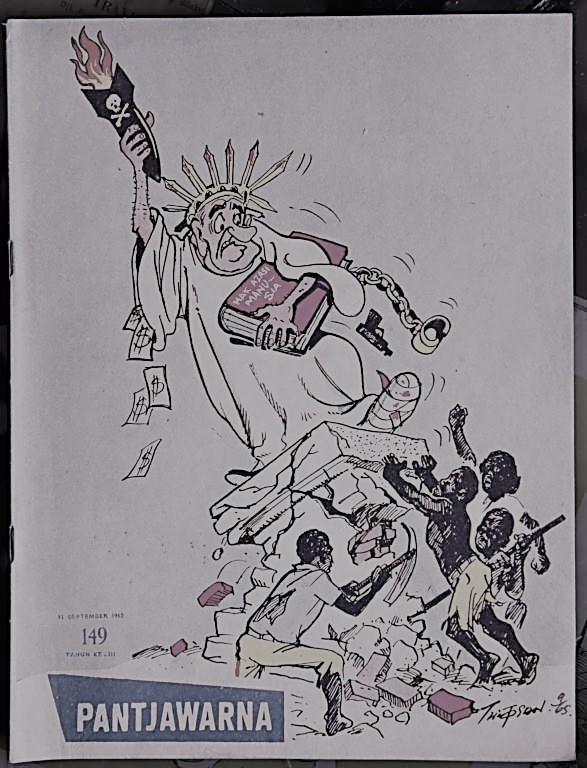

Arsitektur Jengki thus suggests a geopolitical change that had structured a decolonised nation in the postwar era. Most Indonesian architects agree that, in the words of a reporter, “Jengki, was born out of the shift from Dutch colonial rule to sovereign status and America’s new influence in the country.” For some this American influence was not only via the media, but also via the direct involvement of American educators, architects and planners who came (under USAID Kentucky Program) to teach at ITB in the 1950s and 60s, after most Dutch professors had left Indonesia. There is no evidence that American professors introduced Jengki style, but the American presence was everywhere in Indonesia by then—not only in ideas and representation, but also in building materials. For instance, Khalil records that “In 1955, the US provided a loan to develop Indonesia’s first national cement company in Gresik” (p. 116). This leads us to understand that the buildings were indeed unthinkable without cement. And the emergence of the US-supported Gresik Cement ended the monopoly enjoyed by the Dutch’s Padang Cement—which signified at once the beginning of an American era, a political economic shift from “Jan” to “Yankee.”

Yet, it is also the era of Sukarno who yelled to the U.S., “go to hell with your aid!” It was the age of nationalism where we could see Sukarno offering to the daughter of his mentor, HOS Cokroaminoto, a Jengki style “Heroes House,” and as quoted by Khalil: “We, as Indonesians, realise that the nation’s patriots have provided meaningful contributions to achieve our Independence. With regards to those contributions, we Indonesians with great solemnity and honour, present this building as our highest token of appreciation” (p. 127).

If the origin of Jengki architecture is somewhat unclear, at least almost everyone seems to agree that it belongs to a particular period, i.e. the 1950s–60s. It was the time of merdeka, of Yankees, of nationalism, and of chaos. Khalil did not fail to note that the Tan Villa was installed with iron bars to reinforce the gates after it became a target during anti-Chinese pogroms in 1965 (p. 175). All through the book Khalil makes short but valuable comments as an attempt to tell a social history via architecture. He says as much as he can about each building and the social history behind its modernist design. We still are left with only traces, important and fascinating as they are, for further research.

The subtitle of the book deserves an appreciation: “the years of building dangerously” means that Jengki was a kind of symbolic form of political practice. It must have come from the “years of living dangerously”, but it refers not to the recent documentary television series about global warming and the need for architectural adaptation, but to the romantic drama of the 1980s which was set against the political turmoil of Jakarta in 1965, a movie which brought fame to Mel Gibson and Sigourney Weaver. The most memorable figure in the movie, if we agree, was the dwarf ethnic Chinese foreign photographer Billy Kwan (played by Linda Hunt) who knew deeply about Indonesian politics, wayang, the ruling elites, the kampung, and Jakarta which was described in the film as “toytown and a city of fear.” Kwan, the photographer, developed an intense, passionate and tragically demanding relationship with Indonesian politics. Devastated in the end by what he saw as the failure of Sukarno to take care of the need of Indonesian people, he ended his life in desperation. I am not sure how a retro of an architectural trend of the recent past could be understood as at once the product and expression of “years of living dangerously.” Khalil is not trying to be Kwan, but he too is an engaged expatriate, a self-proclaimed photographer who has developed an intimate relationship with Indonesia beyond his profession. He too develops an affection with Indonesian cultures especially those that are considered mysterious, unique or slightly crazy.

But for Khalil Jengki represents not just a visually striking architectural form, but an impetus for a new individual expression which at once represents a search for a collective “national” identity and perhaps also for ideas of a new type of citizenry—and a national bourgeoisie to match. Still, the emphasis on public buildings privileged the elites, and the emphasis on individual houses suggest that that the new generation in their post-war optimism were mostly seduced by the indoors and individualistic expressions. It is also perhaps important to note that Khalil doesn’t map the optimism through the decades to come. We don’t know how the post-war optimism dwindled, and how the subsequent generations have decided to leave behind this stylistic expression. Khalil only shows that post-war Indonesia allowed itself to dream and shape that dream in concrete and cement. He doesn’t tolerate the changes that came after. Consider how he went into the trouble of making sure that the houses he photographed would be devoid of anything that is considered irrelevant of its time, as if only then—when not crowded by other contemporary subjects and objects—the building can show its true self. Attempts were made to restore the building’s authenticity, and if time can’t be fully frozen, perhaps space can be made to resist change; that is, by way of framing what is considered as strikingly the design from the past. The photos he took have no people in them, as if the many people he met for the book could not be part of his temporal construct.

But what does each building mean today, half a century after the “years of building dangerously”? What does it mean when the building is crowded less by the vintage Vespa, but by rapid urbanisation, by becak, Chinese motorbikes and vendors, by today’s colours, sound and gesture? Khalil’s camera avoided such relationships with the current context in which and through which many of these vintage buildings are embedded today. We can sense him falling only for the Jengki of a particular era. The message then is not so much that the Jengki architecture has been demolished and replaced, but that we have simply overlooked the significant presence of this eccentric and magnetic building heritage of the nation-building era.

Retronesia nevertheless is an important contribution to our knowledge of Indonesian architecture, and how architecture can be discovered and written about by anyone outside the profession and from a perspective that is equally insightful. Khalil has showed us in his own way how the 1950s generation respond to, or expressed, modernity in the Indonesian context. While his photographic work dominates the book and thus reproduces the visual canon of architecture as an ultimate object of a collector’s taste and connoisseurship, his field notes for each of the buildings should generate our interest in considering the broader fields of state formation, identity construction and cultural production. In other words, his field notes—many of which contain social, cultural and political concerns—ought to be taken as seriously as (if not more than) his photographic architecture, for they could enlarge the possibilities for further investigation and lead us to seeing Jengki architecture as a device for reformulating, naturalising and contesting social relations in the field of cultural production. Khalil has invited us, architecture and social historians, to seek out more the meanings and effects of these buildings; how they might be understood as playing a role in registering the politics, culture and society of our revolutionary era; how Jengki architecture might be understood more complexly within the specific historical nexus of modernity in the 1950s as well as beyond, before and after the onslaught of the New Order’s developmentalism—which came with its own version of architectural expression. Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss

Abidin Kusno is a Professor in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University and he is currently the director of the York Centre of Asian Research (YCAR). His research interests include global cities, urban/suburbanism, politics and culture, history and theory of architecture, urban design and planning. He is the author of several books in English and Indonesian, the most recent of which include, After the New Order: Space, Politics and Jakarta (Hawaii University Press, 2013) and The Appearances of Memory: Mnemonic Practices of Architecture and Urban Form in Indonesia (Duke University Press, 2010).

Abidin Kusno is a Professor in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University and he is currently the director of the York Centre of Asian Research (YCAR). His research interests include global cities, urban/suburbanism, politics and culture, history and theory of architecture, urban design and planning. He is the author of several books in English and Indonesian, the most recent of which include, After the New Order: Space, Politics and Jakarta (Hawaii University Press, 2013) and The Appearances of Memory: Mnemonic Practices of Architecture and Urban Form in Indonesia (Duke University Press, 2010).