The missing y

The felicitous treachery of the Thai language makes the word for “law” ever precarious: if kotmaay loses its last letter yo yak, it becomes kotmaa—the rule of dogs.

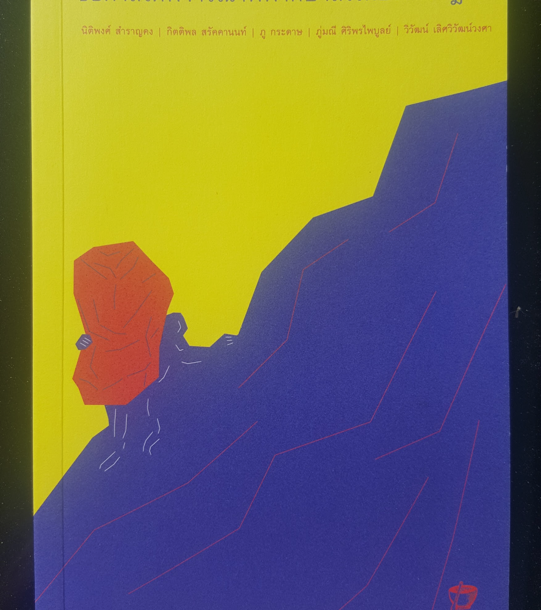

ขอศาลได้พิจารณาพิพากษาลงโทษตามกฎหมา (May the Court Consider Delivering a Guilty Verdict in Accordance with Dogs’ Law), a short story collection, exploits this wordplay to maximum effect. The publisher cut the paper edges just right to produce the effect that the letter y is missing from the title.

The book’s cover depicts a human figure carrying a red object equal to its own weight up a steep hill. Once the figure reaches the top of the hill, the missing y will presumably appear and it will all be worth the trouble.

But the myth of Sisyphus warns us there may be no consolation at the end of the journey, for the journey doesn’t end at the top. As a punishment for defying Death, Sisyphus is sentenced to an eternity of useless labour. For the past several years, much political organising in Thailand has gone through Sisyphean cycles of protest, arrest, legal assistance and then another protest—while the official agenda continues smoothly on its course.

A definitive answer to the “why?” is missing. Why stay in Thailand if you can leave? Why the quest for truth in Thailand if the majority bows to lies anyway? Why reason in Thailand’s absurd politics? This single-edition book of 50 pages suggests some interesting answers.

Outbursts at the absurd

The five authors that contribute to the book are not known for protest literature or overtly political works. On the contrary, their works shy away from social realism and are at most obliquely engaged with the country’s immediate political context. This collection presents an uncharacteristic rawness. A moral monstrosity seems to permeate the pages, ushering in frantic responses from the authors.

The opening story, “A Tale of Torture” by Kittiphol Saragganonda, seems particularly out of character for an author whose signature subtle, elusive style always leaves a lot bubbling between the words. A polemic against self-righteous “good people,” the story relates a torture experiment from the perspective of a “good person” who keeps several slaves in a cellar and recreates aristocratic culture for them. After the slaves become accustomed to luxury, the “good person” takes away everything and forces them to work like beasts. In this dehumanised condition, the slaves reportedly say that they prefer slavery to freedom.

The story reads almost like an outburst of anger on the walls of a public toilet, the narrator’s attempt at coolness a thin veneer over rage at the idea that freedom can only be given at the master’s discretion. Throughout the remaining stories, there are similar outbursts of raw emotion against some monstrous thing. What is the monstrous thing that inspires such outbursts?

Sometimes it is left to the imagination. The deadly hornet in the third story, “Progress in Josef K’s Trial and the Appearance of a Deadly Hornet” by Phu Kra-dart, seems almost intelligent in its buzzing, sending shudders down the spines of the two characters—“you” and “Josef K” (the main character from Franz Kafka’s unfinished novel The Trial). The story is set in an endless eucalyptus plantation, a hellish scene where “you” are tasked with cutting grass all alone, seemingly for eternity. Meanwhile, the menacing presence threatens to kill you for no reason other than the fact that you let Josef K speak his mind about the injustice he faced in the justice system. It is remarkable how such a strange setting makes for a riveting read in the context of present-day Thailand, where underneath the monotony of absurd politics lies constant fear and uncertainty.

Sometimes the monstrosity is hinted at. In the second story, “On the Day Hokkien Stir-Fried Noodles Saved My Life” by Pumanee Siriponpaiboon, there are bizarre coincidences between numbers and names that conjure up ghosts of the 1976 student massacre. The most risky line of the book is in this story, which takes the form of a loser poet’s drunken and desperate rant: “The actual beggars are up there yonder! That gang in the sky and on the screen”.

At other times, there is no ambiguity as to the root of the outbursts. Overt references are made to the military junta in “Nausea” by Nitipong Samrankong. The story’s protagonist is particularly prone to nausea, a sensitivity that is heightened by being transported to a military camp for “attitude adjustment”. The vomit-inducing television programs of the junta don’t help either. The only recourse for the protagonist appears to be the crafting of beautiful poetry in his head, in the midst of forced transportation which leads to nausea which leads to dissociative prose.

Meanwhile the last page of the book declares in italics: “All proceeds after mailing expenses go to Redfam Fund, a fund supporting the families of Ubon Ratchathani red-shirt political prisoners”. This fund has occasionally publicised its need for more donations, since it sends out 1,000 baht to affected families each month. Formerly, the fund cared for about a dozen families but now the number is reduced to four.

While the book blurts out anger, fear and nausea at the absurdities of our human condition, it quietly keeps alive a fund supporting families who choose to continue living despite everything.

To remain creatively maladjusted

Under the current military junta, a Thai slang term has emerged and is widely circulated: อยู่เป็น (yu pen). This literally translates to “knowing how to live” but idiomatically means “playing the game and keeping your head down”. It is an insult thrown at liars and sycophants. Yet the term is ambivalent as it may not only convey contempt, but also humour and resignation, as if to indicate that the speaker doesn’t know how to live under this regime—yu mai pen.

In 1963, US civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. prescribed creative maladjustment as an antidote to a corrupt society. Creatively maladjusted people, out of joint with their time, proclaim truths that seem to fall on deaf ears. But King believed that only through such maladjustment can things change.

This short story collection points to one such maladjustment: to continue engaging in print culture that few people still read. To dare to tell the truth in this rarefied yet still risky platform. To remain outraged by things that have become normal.

So far, the sales of this book have amounted to 14,000 baht—exactly 70 copies sold, and exactly three and a half months of basic sustenance for the families who still draw upon Redfam Fund.

Thailand Mapped กำเนิดเมืองไทยจากแผนที่

‘Thainess’ only truly laid down its roots at the end of the 1970s. ความเป็นไทยหรือการเป็นคนไทยเพิ่งจะลงหลักปักฐานจริงๆก็ในปลายทศวรรษ 1970 เท่านั้นเอง

Why live? The imprisoned witness Waen “stays alive for the six dead in Wat Pathum” according to Nuttigar Woratunyawit, a fellow activist now seeking political asylum in the United States. But what if Waen doesn’t win? What if, like Josef K’s trial, the search for the missing y never ends?

After bail is denied for the umpteenth time, or after a fresh protest results in more cases for an already overextended legal assistance organisation, or after your latest work of literature is launched into the dark and silent universe—you see the boulder roll down to the foot of the hill. Camus’ words echo across time: “The absurd enlightens me on this point: there is no future. Henceforth this is the reason for my inner freedom”. You walk down, contemplating with your lucid mind, as your work is about to resume.

The absurdist response is “why, yes.” Because there is no hope, because there is no future, there is freedom in life. For those of us who “don’t know how to live,” the struggle continues with passion.

Peera Songkünnatham is a writer and translator who lives in Sisaket City, Thailand.

Peera Songkünnatham is a writer and translator who lives in Sisaket City, Thailand.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss