Mataram, the name given to a region and dynasty, has multiple resonances in the history of Java. It is situated in the heartland of central Java, the site of the great 9th century monuments, Borobudur and Prambanan, built by dynasties of which little is known. In more recent times it evokes memories of the rule of Sultan Agung (r. 1613–1646), the greatness of the kingdom he created, together with the splendour of the traditions of music, dance, literature and learning that coalesced under his rule, and were continued by his successors. During it, the on-going melding of religious traditions of both Hinduism and Buddhism with older religious beliefs, and the more recently arrived Islam, continued as part of the broadly shared corpus of belief and practice, identified in English by the awkward, and at times derogatory term, Javanism (kejawen).

Java had long had a place in a trading system that extended from the China sea in the North East, to the Indian Ocean and beyond to the West. From the 10th century onward, trade in the Indian ocean increasingly came under the control of Muslims from regions as varied as the polities within the Ottoman Empire, and coastal cities of the Indian sub-continent. They who were united by a business confidence resting on Islamic law, a trading system that extended as far as the “spice islands” of what is now East Indonesia.

In the late 15th century, Europeans discovered this maritime trading system. First were the Portuguese, who rounded the Cape of Good Hope to enter the Indian Ocean. In 1509 they occupied Goa on the west coast of the Indian sub-continent and in 1511 captured the port city of Malacca. Their strategy was to establish outposts at strategic points on the trade routes, from which to interrupt and gain control of the supply of pepper and other spices to Europe.

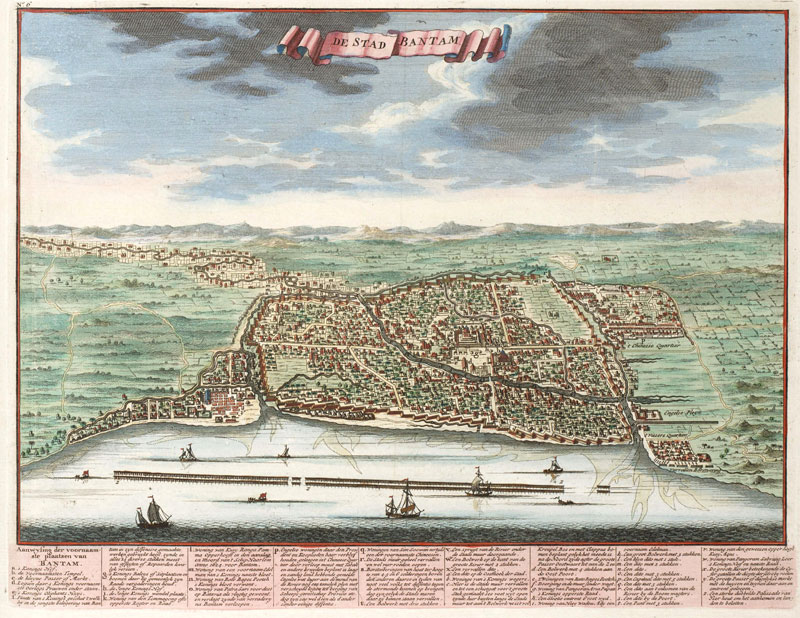

From the 1590s they were followed by the Dutch, who were already challenging Portuguese dominance in the region. The English followed them. In 1602 was the first voyage of Sir James Lancaster. He was followed in 1604 by Sir Henry Middleton, determined to thwart Dutch attempts to acquire trade monopolies via treaties with local rulers. All three rivals had a presence and a reputation at Banten (in European records Bantam), the port on the north coast of West Java where Reid’s story begins, as well as in Japara, Demak, Kudus and other port principalities to the east. In the wake of the disintegration of the dominant power of the earlier east Javanese empire of Majapahit, extinguished by the coastal principality of Demak in 1527, Demak in turn had sponsored the principalities of Banten and Ceribon. By this time, Muslim communities in these maritime centres had reached a critical mass, taking part in struggles for power within and between them, with varying calibrations of attitudes to the traditions of “Javanism”. This made Java, at the time, a land of warring states—between these coastal principalities with each other, and between them and the rice-lands of the interior, along with the competing interests of the European traders. All had their eyes on the emerging inland principality of Mataram looming behind them.

In the hundred years or so between the coming of the Portuguese and the arrival of the Dutch and English, Europe had been wracked by the Reformation. The fact that Britain and Holland were now Protestant, while Portugal had remained Catholic, added the animosities of the Reformation to those of commercial competition.

Such are the principal background elements in the world in which Tony Reid’s novel is set, Tony Reid being an avatar of the distinguished historian Anthony Reid, best known for his masterly Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680. A novel however is not history, and the author of a novel is usually not to be held to much more than date and fact—if that.

Such are the principal background elements in the world in which Tony Reid’s novel is set, Tony Reid being an avatar of the distinguished historian Anthony Reid, best known for his masterly Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680. A novel however is not history, and the author of a novel is usually not to be held to much more than date and fact—if that.

As traditionally understood, the novel involves the creation of characters, their individual complexities, their interactions with each other, and the spaces they inhabit as they progress through time. Themes of love, adventure, religious experience, social and political life, all or some, may be predominant in the narrative, and develop arcs of tension, evident, or artfully hidden.

For a novel to be successful, a number of skills are required.

They include the ability to structure a plot, to sustain a coherent narrative line, strategically situate events to control the movement of this plot and to create convincing dialogue, ensuring that the language registers of its characters are appropriate to their personalities and the situations they are in. There may also the expectation of a presentation of ideas and values, and a view, realised or hoped for, of the human condition that stays with the reader after it has been read.

This is problematic enough when the setting is an author’s own time and culture. A historical novel, a fortiori one set in an environment exotic to author and reader alike, when there is the need to present convincingly the individual ideas, relationships and confrontations of the dramatis personae who inhabit this time and space and to give them a distinctive edge, multiplies the challenges.

Tony Reid’s novel opens on 1 October 1608 as its protagonist, an Englishman, Thomas Hodges, staggers out of his cabin up to the deck of his ship The Red Dragon, to be confronted by the smells, sights and sounds of Banten harbour. This is his first experience of an Asian port city with the multiple ethnicities, religions, cultures and trades by which its population lives. Later in the chapter we learn of his background: where he is from, his earlier career, and something of his personal formation. He is a Hampshire man, a self-confident Protestant, burdened by an unhappy marriage and the death of a son. He had talked his way onto a ship plying the wine trade between Britain and Portugal. After three years he had gained a mastery of Portuguese, and used it to get the position of Master’s Mate on The Red Dragon, a ship bound for the islands of Southeast Asia, where Portuguese was the only language spoken widely enough to serve as a lingua franca and was essential for the negotiation contracts to purchase pepper and other spices for export.

The crew of the The Red Dragon is mixed and includes speakers of Malay brought back to England from a previous voyage. Among them is a Chinese, a long-time resident of Banten taken to England by Henry Middleton, who accordingly speaks some English, along with Javanese. Some of the English crew are Cornish. The significance of this becomes clear later in the novel. The historical moment and movement in which the novel is set, is thus established, and Hodges is placed as a player in an ongoing process.

The Red Dragon casts anchor, and attracts visitors: Bumboats, loaded with fruit, a group of officers from a Dutch ship in the harbour, extending the courtesy of bringing supplies of fresh water, vegetables, and a piglet to be slaughtered for fresh meat. Hodges joins them as they chat in Portuguese, telling the English of their victories over the Papist Portuguese. Then comes Scott, an Englishman left behind for some reason by Middleton’s ship, who arrives on an outrigger flying the British Ensign, overcome by emotion at seeing again some of his fellow countrymen. Finally a delegation of the Banten Port authority arrives and come on board. They too speak in Portuguese, and inform the Master of The Red Dragonof the protocols to be observed if they wish to buy pepper to export to Britain.

AN 18TH CENTURY DUTCH DEPICTION OF THE PORT OF BANTEN (IMAGE: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS)

Hodges is delegated to navigate these protocols, and he goes ashore dreaming of the fruits of a successful outcome of his mission: a share in the wealth from the sale of the pepper in Britain will generate, and possibly win back, the respect and affection of his wife. He steps off the ship, and is drawn gradually into the complex web of local life by personal encounters that inevitably are unexpected, and even arbitrary. They generate consequences unrelenting in the directions in which they carry him, and so, step by step take him deeper into this unfamiliar world. He finds lodgings, how to eat using his right hand, how to present himself to an authority, announce where he is from and on behalf of whom he speaks, the protocols to be observed in an audience with the Shahbandar (Harbour Master), and how he is directed up the line of command to seek an audience with the Sultan for the chop he needs to authorise his ship to export pepper. At a more mundane level, he needs to find, for his ship’s crew, access to liquor and women.

A fracas between sailors from his ship and a group of Javanese men and women attracts his attention. He intervenes and sends the men on their way. By coincidence, among the women are a mother and daughter. The mother, wife of Bintara, a high official, knows the wife of the Sultan, and is thus able to facilitate the access to royalty that he needs. The daughter is the supernally beautiful and wise Sri. They take him home to meet Bintara, and converse in a mix of Portuguese and Malay, Sri interpreting what is said from and into Javanese as necessary. The meeting results in further introductions for Hodges, both to individuals, and to Javanese drama, music and ritual ceremonies. Among them is a séance during which a female shaman—to Hodges shock—calls him forward, and speaks of his dead son Timothy.

He has an audience with the queen, to whom he presents gifts, including a clock. There follows a discussion of time that segues to the truth claims of different religions. Thus Hodges learns something of the religious traditions of Java: of the old all-embracing content and spiritual depths of Javanism, and the more recent inroads of Islam with varying calibrations of tolerance, both of the older faiths, and Christianity.

An assault by a group of radical Muslim youths on a multi-religious courtyard in the Chinese quarter of the city further advances the narrative. Bintara intervenes, and despite Hodges’ attempt to protect him, is killed by the rioters. This is the dynamic that activates the love that has been hinted at burgeoning within the breasts of Sri and Hodges. Sri is distraught. When Hodges comes to explain what happened, at first her grief is expressed in fury against him, but is transformed to a passionate embrace as she realizes what has happened, and how she loves him.

A marriage ceremony is arranged by Sri’s mother, but without the knowledge of her son, Sri’s brother Khalid, who after Bintara’s death, according to Islamic Law, now has authority over Sri.

Hodges, to extend his stay in Java, gets a grudging permission from the commander of TheRed Dragon to travel to Mataram to present a petition to the Sultan, (at this time Krapyak, r.c.1601–1613, whose son Pangeran Anggalaga, the future Sultan Agung (r.1613–1646) is impatiently eager to succeed to the throne) to trade with the English. And so the couple go by boat to Jepara, then to travel overland to Mataram.

They are to spend a number of weeks in Jepara. This stay is a kind of bridge to a second part of the narrative. Hodges is accepted and welcomed as Sri’s husband by her uncle Raden Kajuron. He is carried deeper into Javanese culture: to the celebration of a wedding, to the Javanese shadow theatre and its repertoire drawn from the stories of the Mahabharata. He is introduced to a number of other characters, including Buyung, son of a Chinese cloth merchant eager to leave his father’s tutelage, and go into business on his own.

Hodges, in planning to go to Mataram, upgrades his role to that of an envoy from King James to the Sultan. He finds an eager accessory in Buyung, and they prepare themselves with uniforms and impressive looking documents. Sri is to present herself as an interpreter commissioned by the Sultan of Banten.

They set out for Mataram, on a dangerous journey, travelling inland along decaying roads. Along the way are militias of rival warring states hostile to Mataram. They are waylaid and taken captive by one such group at a ford crossing. Hodges and Buyung are regarded as suspicious, held as hostages, and possibly for ransom. Sri and other Javanese in the convoy are allowed to continue their journey to Mataram.

After a period of time, Hodges proves to be useful to his captors because of his knowledge of firearms. But he is urged to accept Islam, under the threat of torture and death, to prove his loyalty to them. At the last moment, rescue arrives in the form of an armed force from Mataram. Sri has reached the city safely, and thanks to the intervention of a figure named Romo, whom the Sultan had sent a on a rescue mission to escort Hodges, Buyung and their party to Mataram. This is the term of address or reference to a priest in Javanese, though unusual as a personal name, but highlights his role in the story as it continues.

Romo turns out to be a Jesuit who somehow had made his way to Java from Manila, who has lived in Java many years, devoted himself to a study of things Javanese, found acceptance at every level of Javanese society, even the court, and serves a small community of Javanese Christians. Hodges meets Romo. His immediate response is confrontational. Romo is the archetypal foe of a Protestant Englishman born in the first Elizabethan era: a Papist, deceitful and treasonous, holding non-biblical religious beliefs. Surprisingly, he turns out to be English with the birthname Edward Trevithic, and like some of Hodges shipmates, of Cornish origin. Incidental to this is that the Cornish were at this time still a fringe ethnic community in English society, eager for a recognition of its identity within that society. After some aggressive (on Hodges’ part) verbal sparring, they find common ground in astronomy, navigation and optics, prompted by the sight of a pair of spectacles (which Romo finds a boon to his own aging eyes) among the gifts to be offered to the ruler.

Will the unlikely pretence of an English mission solve the problems of the runaway couple? Will the idea of diplomatic relations between distant monarchs even be understood, let alone allowed? Can Hodges do enough to show that he has made his decision for Java, to try to be a true Javanese, ready to support Anggalaga? And can religious conflict between new and old religions be resolved for Java, any more than for England? This the reader must find out, with hints rather than direction from the author.

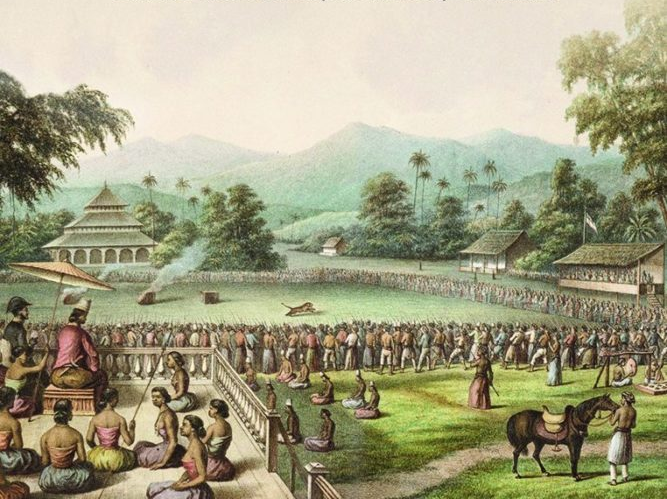

THE PRAMBANAN TEMPLE COMPLEX NEAR MODERN-DAY YOGYAKARTA. (PHOTO: LIAM GAMMON)

There is colour, excitement, high drama, passion and romance in the novel. There is doubt, uncertainty, bewilderment, accounts of conflicting religious beliefs, and problems of conscience. There is a concern and idealism, and there are reflections on what is in Java, what ought to be and what might be.

There are juxtapositions and tensions: between the European and the Asian; between the sturdy Hodges, big bodied, coarse featured, with a reddish beard, and the slender sinuous Sri; between Portuguese (Catholic) and Dutch and English (Protestant); between Islam and Javanism, and within Muslim traditions themselves. It ends on a note of hope and longing.

Fragile paradise: Bali and volcanic threats to our region

The destruction of centuries past should focus the region on preparing for Indonesia’s next mega-eruption.

Of the three principal characters foregrounded, Sri, Hodges, and Romo, Romo is perhaps the most intriguing; son of a Cornish recusant, who escaped the persecution of Catholics after the papal bull excommunicating Queen Elizabeth by fleeing to Europe, becoming a Jesuit, and possibly finding his way to Java in the wake of the missions of Francis Xavier to the Far East. He loves Javanese thought and culture. He makes a translation of the Gospel of Mark into Javanese.

How does it stand as a novel? It is a good read. It takes the reader into aspects of the world of Java as it might have been experienced by early 17th century sailors and merchants. It presents, through its characters, some of the dynamics of the religious beliefs motivating their decisions. There are some weaknesses. Perhaps an over-reliance on coincidence as a device to effect movement of the narrative, to create and release tension. The characters show little internal development. Hodges’ protests against Javanese “superstition” seem couched more in the language of the Enlightenment, than 17th century England. Control of language register is at times inconsistent. Sri’s fluency, in her account of outward difference in the form of characters but the identity of their inner mechanisms, “… they all hear, eat, shit and make love in the same way”, is vigorous. But is she speaking Portuguese or Malay, with Hodges not understanding Javanese? Some of the banter between Hodges and Buyung could be heard in any common room. Romo, as a Jesuit, could be said to exemplify a use of “discernment” on steroids: he celebrates the Eucharist with tempeh (toasted bean curd) and tuak (rice wine) bread and wine being unavailable; he would not condemn Hodges if, to save his life, he made an external acceptance of Islam as the unifying religion of Java; he performs a “conditional marriage” between Sri and Hodges; he christens their son, Andrew.

Tony Reid has produced a complex story, holding in its embrace many elements which take the reader into the world of early 17th Java. But perhaps Professor Anthony Reid should not yet give up his day job.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss

Professor Anthony Johns is Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University for Indonesian Languages and Literature.

Professor Anthony Johns is Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University for Indonesian Languages and Literature.