The 2018 documentary The China Hustle—a movie by Academy Award winning director Alex Gibney about US-banks inflating the value of Asian companies to subsequently sell their worthless stocks to unsuspecting US-investors—features an American banker who gloats about Asia as an investment destination: “The best place to be a criminal is someplace with no cops.”

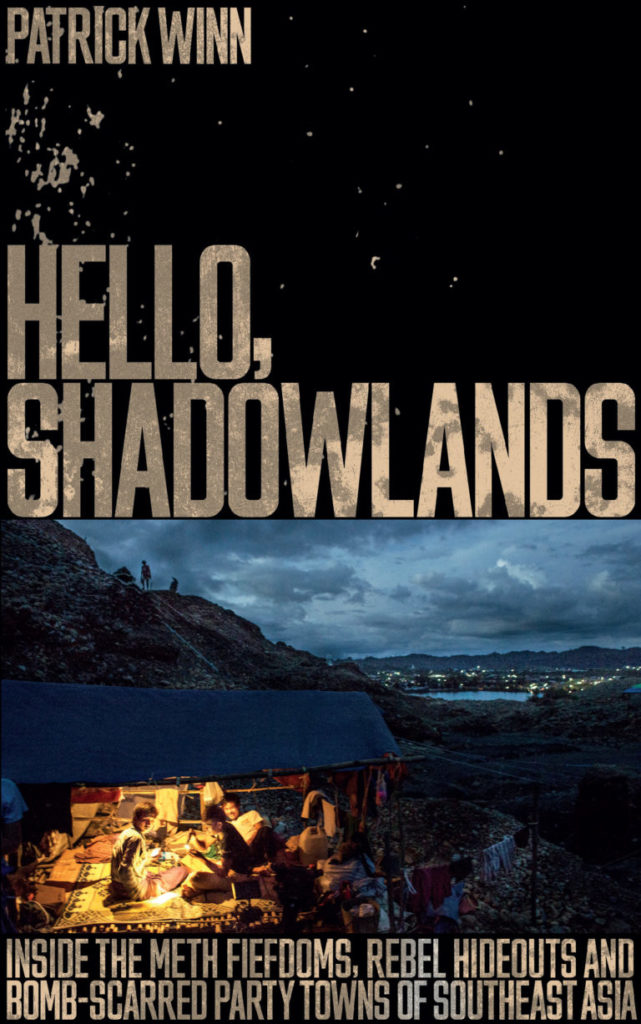

This is also the premise of Patrick Winn’s book Hello, Shadowlands: Inside the Meth Fiefdoms, Rebel Hideouts and Bomb-Scarred Party Towns of Southeast Asia. (The original title of the uncorrected proof copy I received from the publisher prior to a discussion on organised crime in Southeast Asia at Chatham House, a think tank in London, was Hello, Shadowlands: Inside Southeast Asia’s Organized Crime Wave. A recording of the Chatham house discussion with Winn is available here.)

In Hello, Shadowlands, Winn argues that Southeast Asia is in the midst of an organised crime wave that is fuelled by the weakness of the region’s governments. Unable to police their territory, criminal activities flourish in the shadow of Southeast Asian states.

To support his argument, Winn examines various forms of what in his view constitutes organised crime in Southeast Asia. The six chapters in the book explore methamphetamine consumption in Myanmar and how a militant Christian militia (Pat Jasan) is trying to contain the country’s drug epidemic by beating up drug consumers before incarcerating them in private “rehabilitation” centres; the black market for abortion pills in the conservative Philippines; eateries in Thailand run by the North Korean government in search for hard currency; Islamic “terrorists” targeting karaoke bars and sex workers in Thailand’s deep south; as well as vigilante groups that kill dog thieves on the payroll of Vietnam’s culinary establishment.

Winn, an American journalist who has been reporting out of Bangkok for several years, knows the region well, which is evident from the carefully researched chapters. At the same time, a close reading of his vignettes calls into question his assumption that organised crime is thriving in those areas of Southeast Asia where the state is absent.

Arguably, states are at the heart of criminal activities in Southeast Asia. There is ample evidence that military and government officials at the highest level are involved in the production and sales of methamphetamine in Myanmar, while their Thai counterparts are have a stake in human trafficking and the country’s flourishing sex industry. In Cambodia and Laos, the government plays an important role in the logging of protected tropical hardwood and the exotic wildlife trade. Meanwhile, in Indonesia the military and the police compete for control over natural resources and protection rackets in the mining sector. In the Philippines, family dynasties have controlled the legal and illegal economy ever since having captured the local state during the US-American colonial period, while Singapore has been named one the world’s main centres for money laundering by the US Treasury in May 2018.

Terrorist arbitrage in Southeast Asia

Jihadists know how to take advantage of the unique space for mobilisation offered by the Indonesia–Malaysia–Philippines triborder area. Governments are still catching up.

In short, it is not so much the absence than the presence of the state that facilitates and shapes the contours of organised crime in Southeast Asia, an argument made already twenty years ago by John Sidel in Capital, Coercion, and Crime (Stanford University Press, 1999).

The intimate connection between the state and organised crime across Southeast Asia makes the latter a difficult subject to study. Much of it happens “within” the state and little information is therefore to come within the purview of academics and journalists with an interest in such matters. This is amply shown by the fact that most accounts of “organised crime” in Winn’s book are based on interviews with fairly ordinary petty criminals, including meth users, abortion pill dealers and sex workers at the receiving end of moral crusades waged by vigilante groups in the name of Islam. This is perhaps why Winn’s book does not provide any new insights into crystal meth production, the role the Thai military plays in the trafficking of Rohingya refugees, or the role Singapore’s finance sector plays in money laundering in Southeast Asia.

Arguably, Hello, Shadowlands is then not so much an analysis of organised crime in Southeast Asia but an account of how ordinary citizens at the receiving end of systemic and endemic corruption, private sector rent-seeking, arbitrary law enforcement and predatory bureaucracies try to survive and make ends meet. Winn is giving such invisible people a voice, and this is why his book should be read by scholars, development practitioners, and tourists travelling to the region.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss

Michael Buehler is a Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London. His latest book,

Michael Buehler is a Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London. His latest book,