Exile in Colonial Asia is a compact book, but it’s a large book in its treatment of forced migration, prisoner resettlement, and exile across the globe from East Asia to Africa. The ten essays cover people up and down the social hierarchy: rulers (kings, princes, sultans); pretenders to thrones; convicts; and a few pirates and smugglers. The life of a slave might be better than that of a prince, and a prince one day might be a rebel the next, and soon after on a ship to another part of the world. Commemoration in the subtitle means memory. To restore lives lost to the historical record, the authors pick their way through grudging source material—letters, notes, trading company documents, and lists. It’s amazing what a detective-author can resurrect from the dry lists of people and objects buried in archival records.

In the period covered by the book the world was mapped not by countries but by empires: Portuguese, Dutch, British, French, Belgian, and Italian. Colonial authorities and trading companies like the Dutch East India Company (VOC), a quasi-state, removed people from their homelands and exiled them to foreign lands. The globe is criss-crossed with the movements of these people shown on maps drawn by Robert Cribb. Exile was not a peculiarly Western imperialist measure. Indigenous political systems—the Chinese and the Vietnamese, among others—also used exile and prison colonies to expand their territories. Not all the people sent into exile became alienated in their new surroundings. Some adapted by converting to a new religion, or by seizing opportunities in commerce or agriculture.

From ports in the Indonesian archipelago the VOC transported prisoners to the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa. From the French colonies in Indochina 600 prisoners were sent to Gabon on the west coast of Africa and the Congo. The French also sent prisoners from Indochina to French Guiana, New Caledonia, Madagascar, Martinique, and Guadeloupe. High-level political prisoners in the French colonies went to Algeria, Tahiti, and the Marquesas. The British sent Indian convicts to the Andaman Islands which became a penal colony after the Great Indian Revolt of 1857–58. Rebels against British rule in Ceylon were sent to Mauritius.

Prisoners built and fed European empires. Convicts laboured as brick and tile makers, blacksmiths, boatmen, cart drivers and grass cutters, or were engaged in experimental industry and agriculture. Convicts worked in tin mines in Burma, and in Mauritius in silk and cotton production and the cultivation of sugar and coffee.

This historical study on Asia is one of the few that sees fit to include Australia, in this case to illustrate a place that was both colony and penal settlement. In Asia proper we find ourselves in India, Lanka, Java, Singapore, the Malay world, Vietnam, and Burma. Siam is not among the case studies, because it was not colonised, but when the king of Siam visited Java in the early 1870s he saw what might become of him if the British and French decided to take away his crown and carve up his realm. He observed the sultan of Jogjakarta being marched around and guarded by troops. The Javanese sultan displayed the paraphernalia of royalty, but he was a prisoner in a gilded cage, dethroned and demoted within his own country. Native rulers could be packed off to other outposts of empire. Amangkurat III was exiled from Java to Ceylon. The last king of Kandy in Ceylon was sent to Madras. Maharaj Singh was banished from the Punjab, where he was considered a threat to colonial consolidation, and then sent to Singapore. Sultan Hamengkubuwana II of Yogyakarta was exiled to Penang after he opposed the British takeover of Java in 1811. Some exiles became submissive, some were moderate. Some became militant, some were already militant.

The book is not sentimental, but exile, banishment, and forced migration are melancholy topics. I came away empathetic not only with the individuals affected by dire circumstance but also with the authors’ struggles to salvage memories of those uprooted and sent away. Exiles pined for home, and if they were rulers they dreamed of regaining their thrones. Several authors discuss the emotional pain in the exiled life of their subjects. Anand Yang refers to his chapter as a meditation, and Ronit Ricci’s story of the return to Batavia of Amangkurat III’s remains after his death in Ceylon is told with sorrow.

The final essay by Penny Edwards is a fitting end, if not a conclusion, to the volume. Prince Myngoon, the son of a modernising Burmese king in the mid-nineteenth century, was an embodiment of the Burmese monarchy the British had just eradicated. Edwards calls him a trickster who outwitted the British as he darted from Rangoon to Pondicherry to Benares to Saigon. The prince was a subversive figure able to elude colonial administrators trying to keep track of him. His story is shaped by subterfuge that challenged colonial surveillance. Colonial power had its limits.

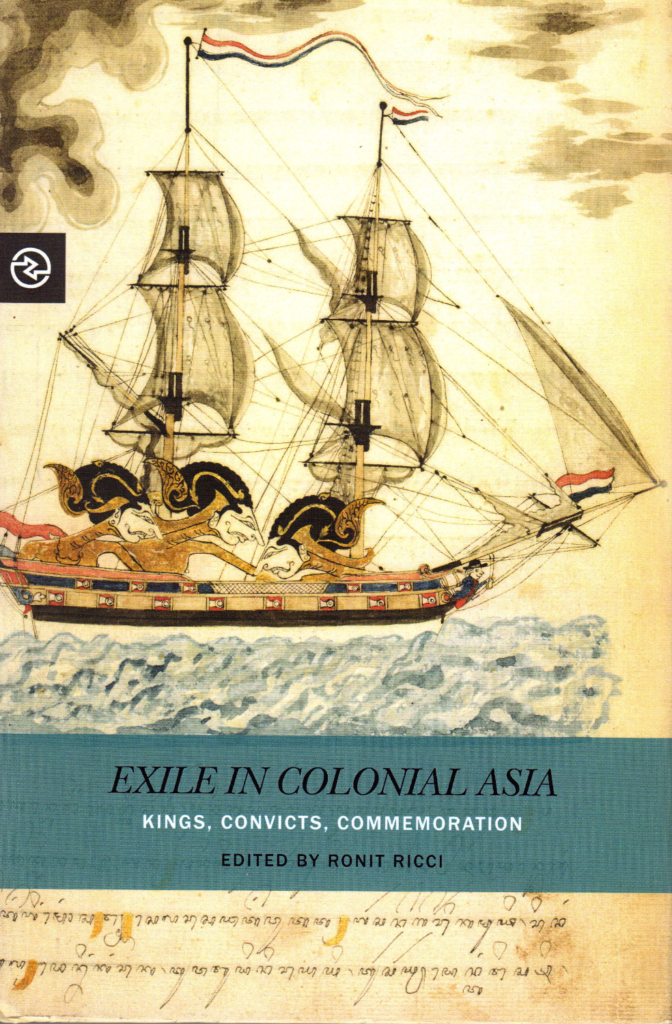

The book is not divided into sections, a bold decision by the editor assisted by Maria Myutel. Cross references cite other essays within the volume to make comparisons and contrasts, but not in a false or jarring way. The book began life as a workshop, that familiar factory of academic production, and the authors apparently arrived soon enough at a consensus about what to discuss. Clare Anderson’s introduction is a masterful account of exile as a global phenomenon that ties the essays together, and the book’s striking cover depicts wayang figures on a Dutch ship that conveys movement, one of the volume’s themes. No surprise that the International Convention of Asian Scholars this year awarded Exile in Colonial Asia an accolade for the best edited volume.

Readers of this book cannot fail to reflect on today’s accounts of refugees forced from their homelands by repression and civil war. History is present knowledge, and each author in his or her essay reaffirms human possibility in an inhumane world.

Craig J. Reynolds

Australian National University | 4 October 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss