Ronit Ricci, Banishment and Belonging: Exile and Diaspora in Sarandib, Lanka and Ceylon, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2019, 282pp, ISBN 978-1-108-72724-2.

For well over a century, Sri Lanka was the Dutch colonial administration’s main site of exile for troublesome Indonesians. From the late seventeenth century, hundreds of ‘natives’ from the Netherlands East Indies who were deemed rebellious were consigned to the island, many never to return. They were a diverse community, including members of royal families from across the archipelago and their retinues, as well as soldiers, convicts and slaves. Among the nobles were kings, sultans and princes from Java, Madura, the Moluccas and Timor. Revered Islamic leaders were also banished there. Conditions for the exiles ranged from tolerably comfortable to miserable, with often tight restrictions on their ability to socialize and travel within the island, and also limited communications with family and peers in the Indies. The psychological toll of separation from their homeland was immense. Many felt humiliated and personally diminished by the experience. Today, the descendants of this exilic community are known collectively as ‘Sri Lankan Malays’ and they have a distinctive culture and identity borne of their peculiar historical experience.

Ronit Ricci has written a most comprehensive and remarkable English-language account of this community and its history. This is not a conventional history centred upon chronologically narrating key events, personages and movements. Rather, it is an ambitious cultural, linguistic and religious history based mainly on Ricci’s meticulous examination of archival and literary sources, but also drawing on her recent field research among Sri Lanka’s ‘Malay’ community. The result is an account of great subtlety, nuance and imagination, which explores the meanings and historical significance of important literary texts emanating from or written about exiled Indonesians. She is also concerned with the process by which this community of ‘Malay’ exiles became a settled diaspora in contemporary Sri Lanka.

Ricci brings a rare and highly developed array of linguistic and cultural interpretative skills to her work. She analyses texts in Indonesian and Malay, Javanese, Arabic, Dutch, Tamil and English but does more than simply describe or translate passages. She carefully explores how terminology has shifted over time and place, analysing why this is and what significance particular nomenclature may have had for the authors of various texts. For example, what today is called Sri Lanka is variously known in the texts she studies as Sarandib, the old Arabic name for the island, Lanka, an Indic title drawn from the Ramayana epic and the place to which Sita is cast, and finally Ceylon, the preferred colonial usage. She queries whether each name, though applied to the one island, in fact represents separate and parallel exilic narratives and perceptions of location and predicament.

Ricci also analyses the interlinear translations of texts—the practice of inserting Malay translations between the lines of the original Arabic language text. She regards these translations as providing ‘a microcosm of the transmission’ of language and meaning. The choice of words in the translations, whether emphasis is given to word-for-word accuracy or to semantic coherence, and even the relative size of the interlinear translations compared to Arabic script, all provide indications how the exiles regarded these texts and sought to convey their meaning.

No part of the text better illustrates the interpretative richness of this work than chapter six, entitled ‘Nabi Adam: The Paradigmatic Exile’. Ricci explores how the Malay community found parallels between its own exilic suffering and Adam’s fall. According to Muslim tradition, the Prophet Adam was banished from Paradise by God for tasting the forbidden fruit and cast to Sarandib, landing on Nudh mountain—a location now commonly known as Adam’s Peak. The story of Adam’s fall is found in many Arab and Persian sources in the tenth to twelfth centuries and was then taken up in later Southeast Asian texts, including those produced by Indonesians. Ricci considers how the exiles identified with Adam’s expulsion to the very island where they themselves were consigned, and also how proximity to the sacred Adam’s Peak allowed pilgrimage and the seeking of blessings and Prophetic intercession with God. For example, in the poet Baba Ounus Saldin’s Syair, it is suggested that just as Adam’s fall signaled the end of his heavenly existence, so too the forced transportation of Indonesians to the same island showed their removal from their beloved abodes. Nonetheless, because of the great spiritual importance of Sarandib/Ceylon as Adam’s resting place, the island offered religious succour and enrichment for the exiles. As Ricci observes, these texts reveal that Ceylon ‘was no longer just a godforsaken place of exile but home to the important Islamic sacred site of Adam’s Peak’ and thus enabled the Malay community to regard this as a ‘return that introduced some measure of familiarity to a foreign land in which, over time, the Malays established a new home’ (148).

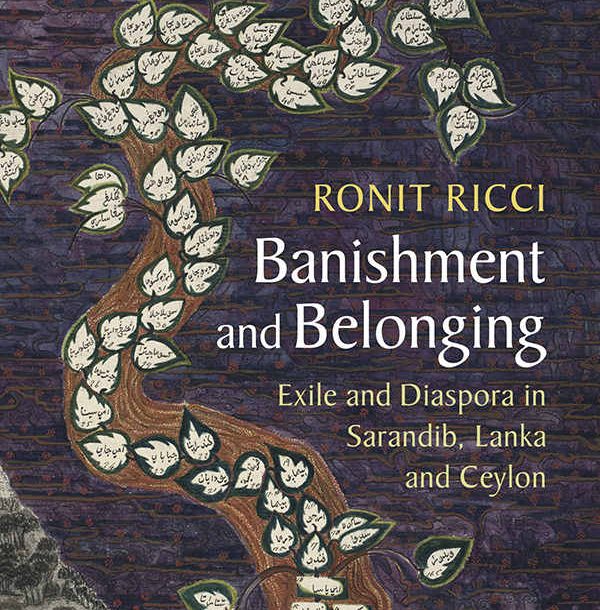

The book is beautifully presented. The cover illustration is a reproduction of the Tree of Adam, showing the genealogical connection from the first Prophet to the Javanese rulers of the early eighteenth century, including Amangkurat III, the first sultan from Java to be banished to Ceylon. There are many images in the text, not only of the literary works being analysed but also of newspapers, maps, letters and photographs from present-day Malay sites in Colombo.

Banishment and Belonging is a superb feat of scholarship. The material with which Ricci is working is often fragmented and challenging to interpret, not only because of the linguistic complexity or frequently baffling allusions, but also because of what is not stated. Indeed, reading her text, it is tempting to see her as akin to a museum restorer painstakingly piecing together remnants of a precious ceramic piece and then musing on how the object’s intriguing form and recondite script and messages might be understood, and moreover, why this work of art is relevant to present times. This is Ricci’s great contribution. She brings empathy and acute insight to her work and allows access not just to a past world rarely seen but also to enduring human efforts to respond to the trauma of displacement and disruption through literature and religion.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss