In his preface to a volume on the filmmaker Takeshi Kitano, Lawrence Chua described the auteur’s works as “[…] like witnessing both a catastrophe and a miracle unfold.” This characterization could be used to describe the interest of Chua’s detailed account of the twentieth-century evolution of Bangkok as a city, when modernisation began to gain speed 200 years after the city’s founding in 1782. As the subtitle declares, administrative plans for the capital of the burgeoning nation-state sought to reconcile Buddhist and/or cosmological conceptions of the built environment—inherited from the nascent version of Bangkok—with the typically abstract rationalism of the modern movement. The often eccentric results, which Chua traces in a series of case studies from across the twentieth century, point to more than the book’s particular aim of excavating local genealogies of modernism.

Ideal family poses in front of their modern home 1941. Courtesy of the National Archives of Thailand

Rather, Bangkok’s (in)famously uneven urbanism is revealed as the consequence of political manoeuvrings and antagonisms; architecture and space are shown as central to Thai modernity, and the ideological usefulness and failures of utopian ambitions are mapped. In the latter respect, the shifting meanings of modernity in Thailand across decades are highlighted. Chua’s penultimate chapter on the impact of late capitalism brings to mind US writer Gary Indiana’s description of Bangkok in the 1980s as “[…] a, smelly, traffic-crazy, scary city full of […] strip joints, streets vendors, colonies of homeless people, and mind-boggling poverty.”

But Bangkok Utopia does not aim to indict. Southeast Asia, like many regions, has been conventionally relegated to the margins of canonical histories of modernism; to be, at best, treated as a source for raw material for paradigms and theories established by Western-centric worldviews. Chua, a historian based at Syracuse University, instead seeks to understand how localisation was central, not exceptional, to the spread of architectural forms that initially emerged in the industrialising centres of Europe. His previous writings, for example, considered variations in modernist idioms within the rise of fascist cultures in Italy and Germany. This, of course, points to the (extreme) political malleability of the architectonic. By examining a country like Thailand, we not only push beyond a centre/periphery and/or West/East binary but also begin to clear away a narrative that the “third world” has been a dumping ground for failed “western” experiments in utopian modernism.

Sala Chaloem Krung Cinema Bangkok 1932. Courtesy of the National Archives of Thailand

In tracing the specifics of utopian thinking through the shift from Siam to Thailand, from the era of absolutism to the struggles of constitutionalism over subsequent decades, the book creates a compelling history of how urban and infrastructural planning seeks to shape a population’s sense of national belonging under sovereign conditions. And Chua also wrests utopian thinking from being necessarily discredited, by concluding that contexts, not buildings, and the cooptation of the “speculative imagination” of architects, retard the progression of what he enigmatically refers to as “a collective becoming.” In less literary terms, this points to Pedro Levi Bismarck’s characterisation of a historic shift from architecture-as-project to architecture-as-object, because of late capitalism and/or neoliberalism-and the consequences of which the Indiana quote above dramatically visualises.

Organised around three major thematic sections titled ‘Tools,’ ‘Materials,’ and ‘Systems,’ the structure is intended to mirror the methodology of an architecture studio, from conception to realisation, and then the broader contexts to which any built environment relates. This allows Chua to pursue a range of inquiries that includes the revision of ancient Pāli descriptions of the heavens in terms of modernist geometries and how the growth of a Chinese urban class sought to assert kinship through architectural appeals to “their” dynastic past. Further, Chua explores how the introduction of air-conditioning could underwrite notions of “civilization” and partially secure ideals of democracy as different classes now shared the new and comfortable leisure spaces of the twentieth century. And, finally, there is the coming of the Cold War and the emergence of “development” as a supplanting of democratic ideals, linked to the dictatorship of Sarit Thanarat (1957-1963) and heavy US investment to establish Bangkok as a consumerist mecca and thus as a bulwark against the spread of communism.

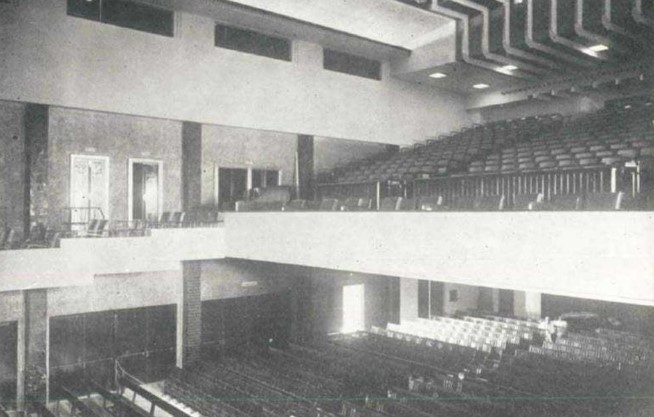

Interior of Sala Chaloem Krung Cinema Bangkok. Courtesy of the National Archives of Thailand

Bangkok Utopia is the most recent, and most scholarly, attempt to unravel the complexities of Bangkok as it evolved in the twentieth century. Descriptions of the extreme contrasts to be found in the Thai capital have become so familiar as to be a literary cliché but, nevertheless, given current aggressive attempts at gentrification in downtown Bangkok on behalf of PM Prayut Chan-o-cha’s dictatorial government, we should keep in view what Chua acutely grasps here: questions of the politics of architectural form and space. Unlike previous volumes such as Marc Askew’s encyclopaedic Bangkok: Place, Practice and Representation (Routledge 2002) or Philip Cornwel-Smith’s Very Bangkok: In the City of Senses (River Books 2020), to treat the city as technocratic or as a product of the “fact” of “culture” is to miss examining the vested interests that shape it. Further, as Chua implicitly suggests throughout the varied concerns of the book, forms and spaces aim to act on us, to shape bodies and subjectivities one way or another. The image of Bangkok that emerges is one of a powerful crucible for ideological experiments on behalf of a range of elites. A recurring range of street protests in Thailand since the beginning of this century are violently contesting their legacies and demanding new visions of a future. Utopian ideals are not lost.

Chua’s achievement is published as part of the University of Hawai’i Press’s series titled ‘Spatial Habitus: Making and Meaning in Asia’s Architecture.’ Hopefully this purview won’t seem too narrow to potential readers as Bangkok Utopia is a rich resource and timely in view of the rise of Asia-as-method and decolonial methodologies and theories. And it proves the health of new studies of visual and material artefacts and cultures outside their traditional disciplinary domains.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss