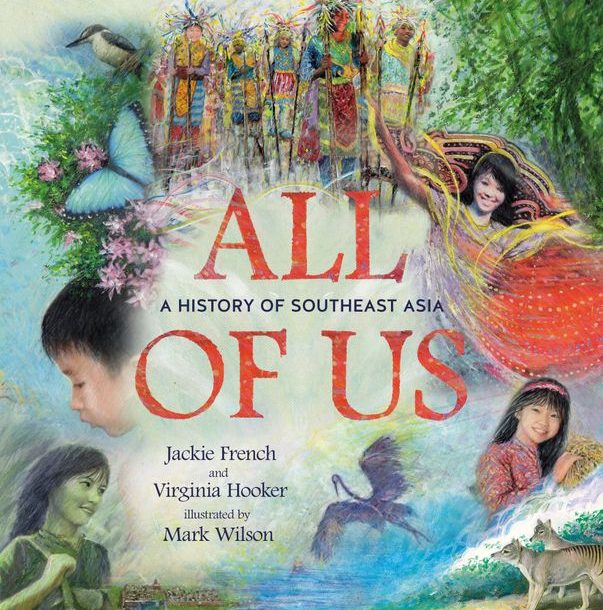

It has been observed, perhaps rather too often, that one should not judge a book by its cover. A casual glance at the charming cover design of All of Us might well suggest that the book should be an enjoyable and perhaps even educational read for sub-teens detailing the history, culture and lives of Australia’s Southeast Asian neighbours. It is in fact a work that deserves to be studied as a matter of urgency by any Australian of any age at all interested in their nation’s future.

Indeed, no less might be expected from the galaxy of distinguished contributors involved in its production. Professor Emeritus Virginia Hooker is acknowledged nationally and internationally as a pre-eminent scholar in her field of Southeast Asian studies. Jackie French AM was Senior Australian of the Year in 2015 as well as Australian Children’s Laureate, having authored some 140 books including the award-winning Diary of a Wombat, charting the lifestyle of the most endearing inhabitants of our continent: ‘Monday, slept. Tuesday, slept. Wednesday, dug a hole.’ And Mark Wilson is another multiple award-winning author and illustrator. Their combined efforts here amount to an invaluable and for practical purposes well-nigh indispensable guide to the region of greatest significance to Australia. It must also be without doubt the most accessible such guide.

The All of Us of the title refers to the ten member countries currently constituting the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) with a total population of rather more than 661 million, about 25 times that of Australia, and a combined Gross Domestic Product of rather more than $3.1 trillion (US), more than twice that of Australia. It is estimated on these figures to become by 2050 the fourth largest economy in the world, with the third largest labour force. These basic statistics would be sufficient in themselves to indicate why Australians would be well advised to familiarise themselves with the present and future prospects of this international grouping, especially as the members of that grouping tend to display only limited interest in familiarising themselves with us. Even more compelling grounds for embarking on such a process of familiarisation are provided by authorities such as Professor of Strategic Studies at the Australian National University and former Deputy Secretary in the Australian Defence Department Hugh White in his disconcerting wake-up call, The Jakarta Switch: Why Australia needs to pin its hopes (not fears) on a great and powerful Indonesia. This is a nation which will inexorably become greater and more powerful than this country, if it is not so already.

Some further statistics are relevant here. And All of Us provides some of the most essential ones with a quite phenomenal ‘Timeline’ extending from circa 200,000,000 BCE to 2011 CE, listing most of the most significant events in the development of most of the countries in question. This is indeed quite a timeline, and one could well suppose that the most distinguished historian responsible would have welcomed a little more space in which to clarify some of the more complex issues listed here. ‘1978: Vietnam invades Cambodia to stop Khmer Rouge brutality’ might for example have been expanded to advantage by noting that the Vietnam invasion was actually provoked by the completely lunatic Khmer Rouge intrusions into the territory of a neighbour with seven times the population of Cambodia and demonstrably one of the most formidable armies in the world. As Colin Cotterill’s Dr Siri observed: ‘the heroic Vietnamese…. created the Pol Pot dynasty and watched while he murdered two million people. Their crime isn’t that they’re invading: it’s that they’re invading four years too late.’ But the essential reality is that the immediate effect of the Vietnamese intervention was indeed to bring an end to the KL genocide, probably the most appalling outrage ever inflicted by a regime upon its own people. It was of course an intervention for which Hanoi was fiercely denounced by Washington and London. And Canberra.

Similarly, one’s enjoyment of Jackie French’s delightful counterpoints to Mark Wilson’s delightful illustrations might be somewhat disturbed by the concluding stanza: ‘Cyclones rip, tsunamis crash, But then our hands extend. And like the heron, all we see, Is all of us, and friends.’ One is inevitably reminded, for example, of the appalling bloodbaths consequent on what the great American military historian Ronald H. Spector called ‘The Ruin of Empires:’ millions of dead in wars of liberation, especially the thirty years struggle for Vietnamese independence, the devastation of East Timor, the Cambodian genocide, what Indonesian artist Dadang Christanto characterised as ‘The Unspeakable Horror’ of 1965/66 in his own country and the devastation of East Timor. But again, the astonishing reality is that ASEAN today is, in the words of distinguished Singaporean academic and diplomat Kishore Mahbubani, ‘the region’s peacemaker. It has absorbed and is implementing the culture of peace.’ By contrast, ‘the three economic giants of Japan, South Korea and China have failed to create a comparable Association of Northeast Asian Nations … the consequence has been that the only fora where the three Northeast Asian leaders can meet comfortably and discuss common challenges have been the meetings convened by ASEAN…’ Indeed, Mahbubani suggested that ‘EU should be taking lessons from ASEAN on diplomacy, not vice versa.’ And this was written in 2008, long before the excruciating rupture of Brexit left the EU a seriously diminished enterprise.

What makes this achievement truly astonishing is, as Mahbubani points out, that ASEAN is the most ‘balkanised region in the world: ‘no other region is as diverse – in religious, ethnic, cultural and political terms – as Southeast Asia,’ with a population comprising in general terms some ‘300 million Muslims, 80 million Christians, 150 million Hinayana Buddhists, 80 million Mahayana Buddhists, and 5 million Hindus. Some Vietnamese Buddhists also practice Taoism and Confucianism, in addition to being Communists.’

Writing history in the Indian Ocean world

Writing history in the Indian Ocean world was the result of a complex interplay of global norms and local conditions of textual production.

It is enough to make one wonder if there might even be a place for us in All of Us. The question is all the more deserving of serious consideration at a time when, as Channel 9 political editor Chris Uhlman observes, we have compelling reasons to regard China as a potential strategic threat and the United States as very much an unreliable ally. We should therefore, he urges, ‘deliberately diversify our suppliers away from China. Every dollar spent building capacity in countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Bangladesh and India is a dollar well spent. Their progress is our progress.’

Former Australian Foreign Minister Gareth Evans speculated more than twenty years ago, in an era more open to such visions, that Australia might well become ‘the oddest one in’ ASEAN, rather than the ‘the odd one out.’ The prospect makes more sense than ever at the beginning of the 21st century. Assuming we still have a choice.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss