It’s coming to June. Singapore is almost halfway through the Bicentennial, the commemoration of two hundred-slash-seven hundred years of Singapore history. Three months ago I wrote about the problems surrounding this “slash”—the attempt by the SG Bicentennial committee to dance back and forth between 1819 and 1299 without critically dealing with either. Such a manoeuvre, I argued, can take the form of erasure, giving a performance of progress without enacting it with sincerity.

Private: The Singapore Bicentennial: it was never going to work

On the unstable historical foundations of Singapore's (supposed) two-hundredth birthday.

What can we understand about the Bicentennial—and Singapore’s “post”-colonial condition—when these three events are placed side by side? What juxtapositions, contradictions, and surprising commonalities emerge? The goal of this series is to begin answering these questions.

In Part One below, I explore Arus Balik—From below the wind to above the wind and back again—at the Nanyang Technological University Centre of Contemporary Art, an exhibition from 22 March to 23 June 2019. It is the only event that is still ongoing, so do catch it if you can (admission is free).

Arus Balik (Photo by author)

Arus Balik—From below the wind to above the wind and back again

Gillman Barracks was central to the British military’s colonial project, the location of which was chosen because of its prime proximity to the south coast and the sea (sans the now-reclaimed land). It is apt, then, that NTU’s Centre for Contemporary Art—which dwells in this historical compound—is housing an exhibition about the geopolitics of Southeast Asia’s maritime history as its response to the Bicentennial.

Using renowned Indonesian author Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s epic novel Arus Balik (“turning of the tide”) as a starting point, the exhibition charts a meandering path along the Straits of Malacca, the South China Sea, the Java Sea and the Indian Ocean, among others and their coastlines. Even their program booklet refuses to be linear: my friend and I navigated the jumbled paragraphs on the giant unfolded page as if it were a map of uncharted territory while we explored the exhibit.

“Map” of the exhibition (Photo by author)

In this space, bodies of water give way to the notion of bodies in water to explore the difficult relationship we’ve had with the sea and what it represents.

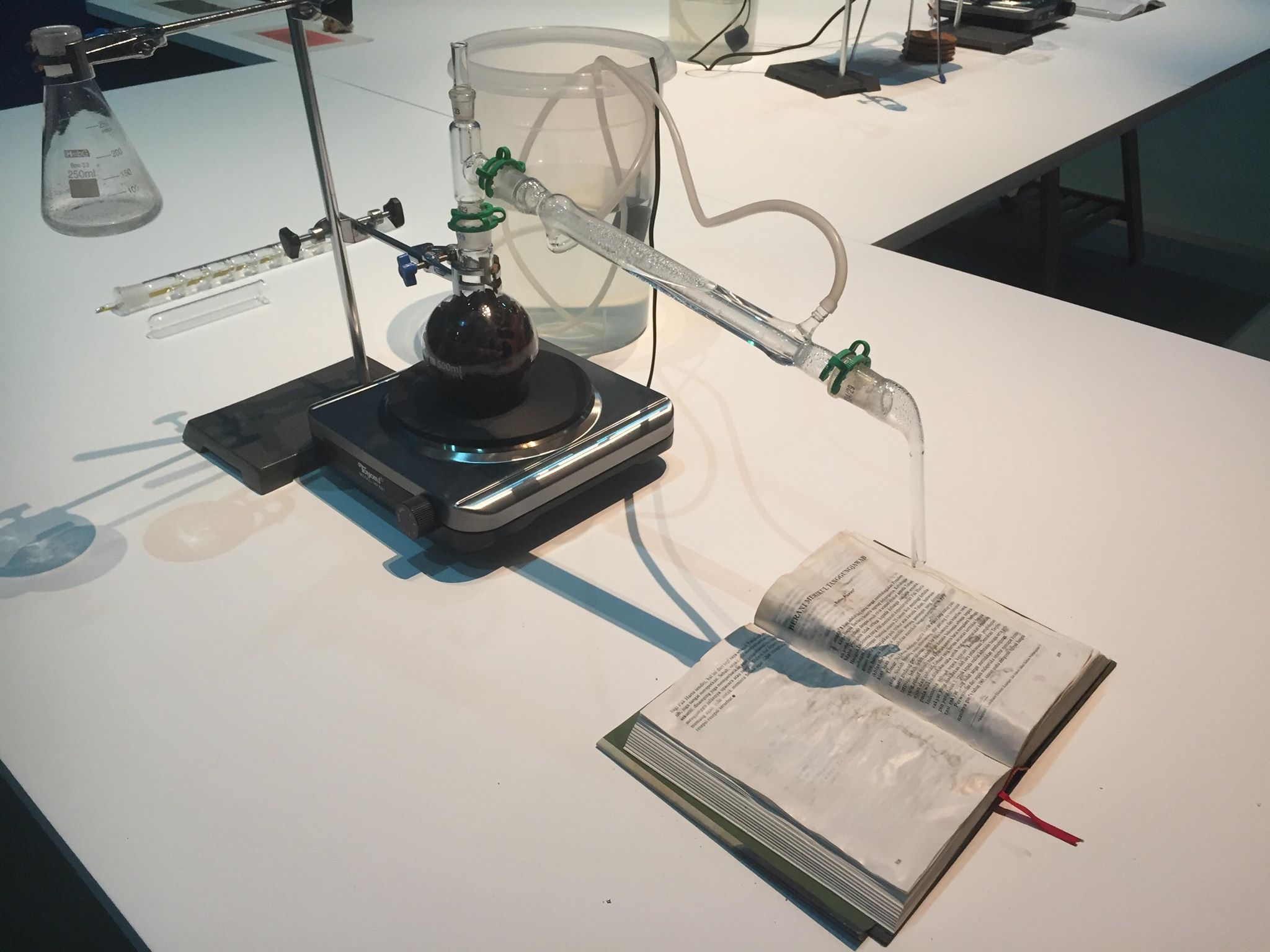

Jakarta-based artist Ade Darmawan distils spices and seawater (the key ingredients of classic colonialism) onto the body matter of Suharto-regime books on land and resource policy, soaking and staining the pages. This impertinent gesture and critique, juxtaposed by the coolly scientific nature of the laboratory setting, explicitly connects the colonial context with the national one.

Ade Darmawan’s ‘laboratory’ (Photo by author)

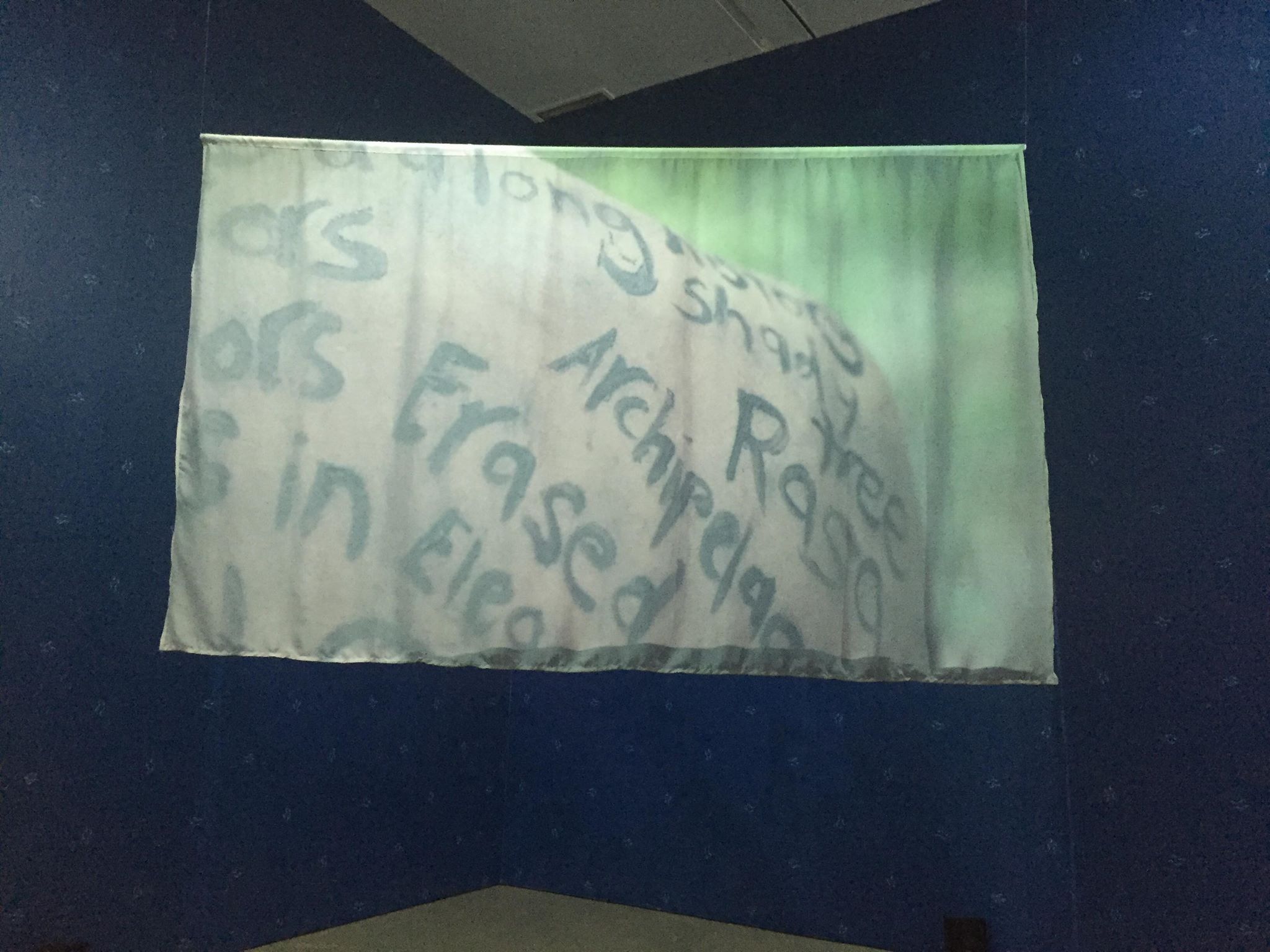

In the video-installation bekas, Singaporean performance artist ila critiques the logos in another way, by scrawling text onto her naked skin, all over her body, with black ink. These words are terse testimonials of “Malay Singaporeans” (a racial category with colonial origins that persist in present day governance) describing, when prompted by the artist, what it means to be Javanese/Boyanese/Batak/Bugis and so on: an impossible question to answer. The camera’s gaze on her inscribed body is reminiscent of anthropology’s original fascination with the exotic Other and their body art as representations of cultural identity markers.

ila’s bekas video art installation (Photo by author)

She then exposes her body to the sand, sea and hot air on reclaimed areas of Singapore. On film, beads of ink mingled with sweat and seawater roll off her skin and dissolve into mere traces. Bekas, then, is aptly named: the word is both an adjective, meaning “former” or “past”, and a noun meaning “trace”, “remains” or “container”. What traces of our deeper past do our bodies contain, if any? As Rebecca Schneider reminds us to ask, what remains? How are our identities written over, erased, appropriated, forgotten through the process of colonialism and in so-called “post-colonial” times?

If ila’s piece dwells in the liminal place between sand and sea, Filipino activist and filmmaker Kiri Dalena’s short film From the Dark Depths (2017) submerges itself completely into the ocean from the get-go. Based on the true story of an activist who was drowned, the film opens with a woman dancing slowly on the seabed, with a graveyard of red flags around her. As I watched her, I had to remember how to breathe. A body floats above her, but she can’t reach him in time as the currents pull her back. Such sublime underwater sequences are interspersed with real footage from Dalena’s own archive spanning two decades of political unrest and, in recent years, tyranny in the Philippines. Finally, the body is taken to shore by a group of men and wrapped in banana leaves. The woman, drenched, begins to mourn beside him.

From the Dark Depths opening scene (Copyright of Kiri Dalena)

In the program booklet, Philippe Pirotte (the curator of the exhibition) asks, somewhat optimistically, “Have the multiple colonisations in Southeast Asia alienated the people from the sea coast? Is it possible to attempt a return?” Pirotte talks of “the reversal of the colonial fact, the promise of reversal of a geopolitical, cultural, and social system”, and how the 1955 Bandung Conference embodied this reversal with the force of a tidal wave (citing Afro-American author Richard Wright).

The exhibition he curated, however, seems to hint towards the absolute futility of such a reversal. There is no turning back from the trauma of colonialism, which—as the artists in this exhibit attest—rears its head in many different forms in the present. Or, to quote Haresh Sharma, the playwright of Civilised (to be discussed in Part 3 of this series), “There is no past without colonisation, and there is no future without it.”

To be continued.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss