We’re pleased to bring you the second part of our series of podcasts that scrutinise the stereotypes that colour the world’s understanding of Southeast Asia’s fastest-growing economy.

Associate Professor Ronald Mendoza is the Dean of the Ateneo School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University. An economist by training, his recent research has focused on the economic effects of one well-known feature of Philippine politics: namely, the prominence of members of political dynasties in elected office.

In this interview, he talks to New Mandala’s Philippines editor Nicole Curato to address the question of whether political dynasties actually engender poverty in the Philippines. You can listen to the audio of Nicole and Ron’s conversation below at Soundcloud, or via iTunes or the Apple Podcasts app.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

Nicole Curato [NC]: I think it’s important to start this discussion by being clear about what we mean by political dynasties. So what do you mean by dynasties in your work?

Ronald Mendoza [RN]: Well, when we’re trying to explain our work, essentially there’s a common definition and that is that if an elected official, a politician has relatives who were in power or are in power as elected officials as well, then we consider these politicians as political dynasties or part of political clans.

There could be a legal definition to it which is to be differentiated with the common definition in that if you want some kind of regulation, some kind of law, some kind of element in a constitution that somehow regulates this pattern of governance, then you need to have a legal, a more precise definition of what types of relationships you will actually prevent.

Philippines beyond clichés series 1 #1: Catholic country

Jayeel Cornelio talks to Nicole Curato about the under-appreciated level of religious diversity in the Philippines.

NC: Right. And are there any objections to the kind of definitions you have put forward? Because you brought up a temporal aspect to it, had family members in power before or have family members in power currently. How important is that distinction?

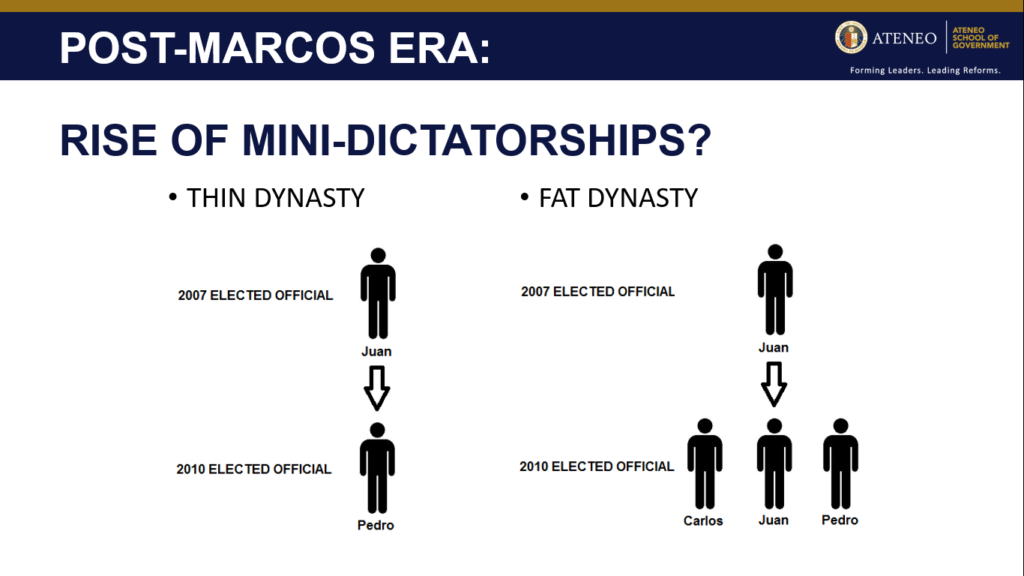

RM: It’s a very important distinction because in the way that our governance has evolved in our ongoing democratic transition, there is a degree of power consolidation among political clans such that if you have many relatives in office, it gives you an advantage relative to those running who do not have relatives in office. So, if you for instance ban the dynasties that have a longitudinal link so across time, you’re essentially controlling for what we call as thin dynasties.

NC: Thin dynasties?

RM: Right. Because they’re sort of following each other in an orderly way.

But if you ban those who are simultaneously occupying office so those who are running for office who actually have another relative who is also running for office or is in office already, that is what we call fat dynasties. So, it’s over time and across offices.

Image courtesy Ronald Mendoza

So, for the type of governance pattern that really concerns us, it’s really those fat dynasties that we’re concerned with because what essentially happens is that the checks and balances in our local government is weakened when a political clan has several members who simultaneously occupy power.

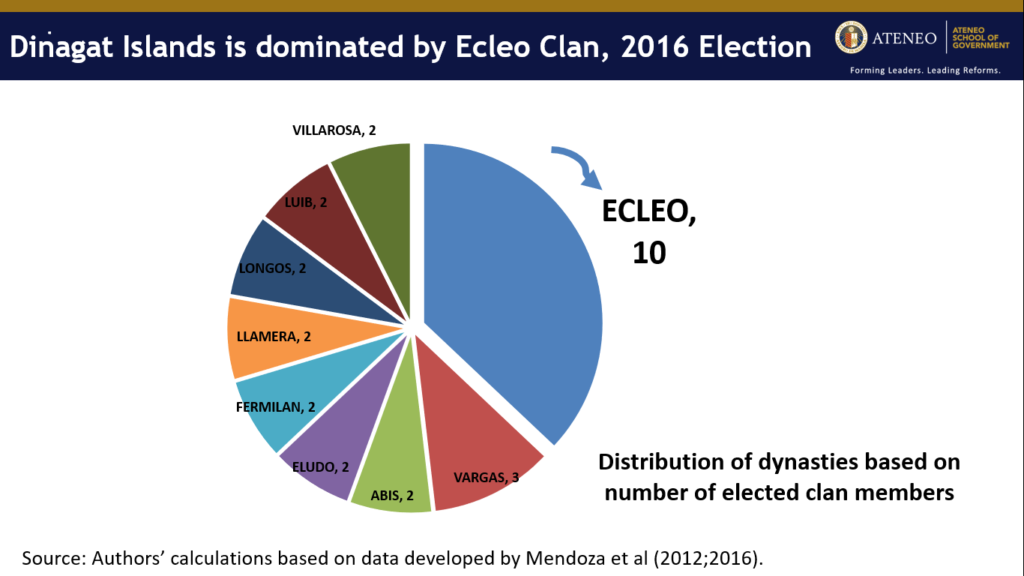

For instance, a governor—and I’ll give you an example, one of our provinces actually has this governance pattern. A governor is the matriarch, the vice governor is one of her sons, three of the mayors are actually also her children, so the vice governor and three of the mayors, three of the five mayors are actually related to the governor. And they would like to beat the incumbent congresswoman right now and take over that office as well and they have, I think two family members also in the provincial board which is essentially that entity in our local government structure that is the check and balance for the governor. So, if the governor has a development plan, a budget, this needs to be cleared by the provincial board. But if you also hold the board, then there is a less of a sort of correcting mechanism for anything that might go wrong as far as the governor is concerned.

Image courtesy Ronald Mendoza

Now, there are also issues of conflict of interest and unfairness if you actually have a governor interacting with you know, mayors and some of the mayors are actually her children. So, there could be a bias towards allocating resources towards the family members rather than to the poorest places in that particular province.

And there are studies that actually basically find this, that there is a bias not in favour of development outcomes, nor of policy targets, but there is a bias towards family members. And presumably the goal there is to actually strengthen their hold on power and their electability.

So, back to your question, what pattern are we more concerned about in terms of dynasties? It’s really the fat dynasty that we are studying and that we are tracking.

In our empirical analysis which was published in Oxford Development Studies, we found strong evidence that the fatter the dynasties, the deeper the poverty becomes particularly in places outside of Luzon. And in Luzon, the finding is not so strong and we hypothesise that essentially there are things in Luzon, in our democracy that might actually mitigate the concentration of power which political dynasties are able to do but the farther away you are from Luzon, there are less checks and balances and less mitigating factors.

For instance, there could be less schools, there could be less civil society groups, there could be less media, there could be more poor people, more underdevelopment, and that in effect increases the probability that the concentration of political power goes in the wrong direction and is actually abused. And what results is impunity.

NC: Right. Because in one of your pieces with some of your colleagues, you framed this as a chicken or egg argument, right? So is it a matter of poverty bringing about dynasties or dynasties engendering poverty. So, could you talk to us more about the kinds of variables that make the stories more complex on the ground or in particular case studies?

RM: Yes, and you’re right. It’s actually quite a complex relationship between the governance pattern and final development outcomes like infant mortality, poverty, GDP per capita. So, what we’re trying to do here is try to develop metrics for a governance pattern that we have identified is quite present in the Philippines. And then what we’re trying to do is empirically test whether this governance pattern is strongly associated with particularly poorer development outcomes.

NC: Could you give an example of a governance pattern?

RM: Well, this is the governance pattern that we’re trying to test. It’s the presence of fat dynasties. So, for instance, at the provincial level, this is our dataset that we’ve developed. Covering 2000 until the present, we have the provincial leadership for the entire Philippines during this entire period.

And what we did is to develop metrics to measure different degrees of concentration of power as reflected by the presence of political dynasties. So, this is essentially the theory that underpins why we’re interested in dynasties in the first place. If the governor is related to many of the mayors and the congressman, and the provincial board, there is such a concentration of political power wherein you can go in at least two ways. One is to use all that power to really push for development and push for bold ambition at that local level. Or you can go another direction and essentially because there is weak checks and balances, you can go in the direction of impunity and use all that power in the wrong way and actually abuse that power. So, the argument has been that with that concentration of power, you can do a lot of good things. This is how some of the political dynasties are justifying—

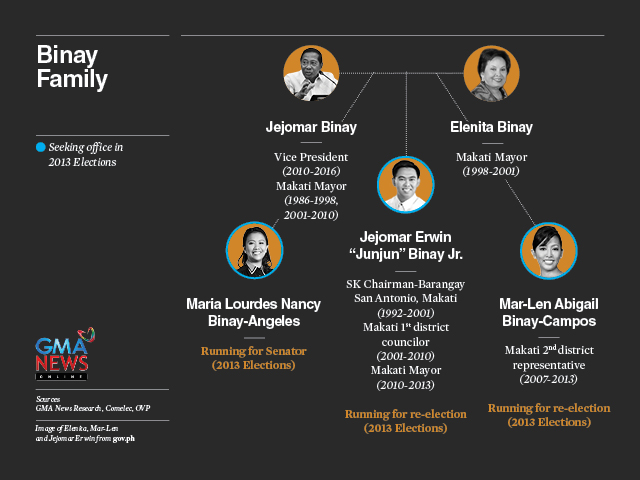

NC: —Makati comes to mind, right? I mean the Binays are very much celebrated for the “brand of service”. And I’m doing inverted commas here. (laughs) So there is a sense that because they have distributed welfare so well to their constituents from a robotics laboratory and a public school to sneakers for school children, there is a sense that—or an argument to be made that there is continuity when you have this brand of service. What does your study tell us?

Image: GMA News Online, reproduced with permission

RM: Well, in fact our main focus for our study is not the big cities like Makati City. Makati City, of course, is one of the richest cities in the Philippines. But the focus of our study is really the provinces. That’s the locus of our analysis and the provinces are important because they are supposed to have been empowered under the 1991 Local Government Code which essentially is the Philippines’ effort towards strong decentralisation. And the goal there was to bring government closer to the people, give them the agility that they need to craft their own development plans, and strategies, and basically incentivise them to mobilise resources so that those resources meet their ambition as these different sub-national jurisdictions, right?

So, Makati is interesting in that it was already a wealthy place when the Binays took over and that’s not the only place where you have political clans. So, Taguig City also has a political clan, Quezon City also has a political clan. And these cities are actually the home of some of the elements of a strong democracy, such as really good schools, an active media, an active civil society, and of course an international community to the extent that you have foreign investors and you have some of our development partners also located there. So, I think my hypothesis there is that in these big cities, the concentration of power is not absolute and that the abuse of this concentration of power actually is prevented, mitigated by other factors. So, it’s quite a complex situation.

But, in the provinces where you actually have less of the other factors, we tried to account for them in our empirical analysis so that we can also see what are the mitigating factors in let’s say a poor province in the south, right? In some provinces you have—these provinces are prone to conflict. In some provinces, they are rich in natural resources like mining. In some provinces, they’re landlocked, in some provinces they have ports.

So, what we tried to do is to try and—to the extent possible—absorb this all in our empirical analysis and reflect it so that we can see what are the factors that interact with each other and what are the factors that exacerbate the effect of concentration of power and what are the factors that sort of mitigate it. And the main finding that we have is that with fatter dynasties and areas outside of Luzon, which is the main island of the Philippines, the impact of fat dynasties is really to deepen poverty.

NC: I like the way you described what’s precisely wrong with dynasties. In a way it’s not really just the proliferation of people with the same last names but what it symbolises, which is really the concentration of power. And that is essentially what is corrosive to democracy because democracy is about humbling power, it’s about redistributing power, and so the argument can also be made that when we think of political clans, they’re not homogeneous.

RM: Yes.

NC: There can also be intra-clan competition that allows for some level of political contestation among fat dynasties. So how does your study account for that?

RM: Actually, that’s a very important point to the extent that democratic institutions can mitigate the concentration of power, so can other clans, so can the threat of a new political clan replacing an old and fading one.

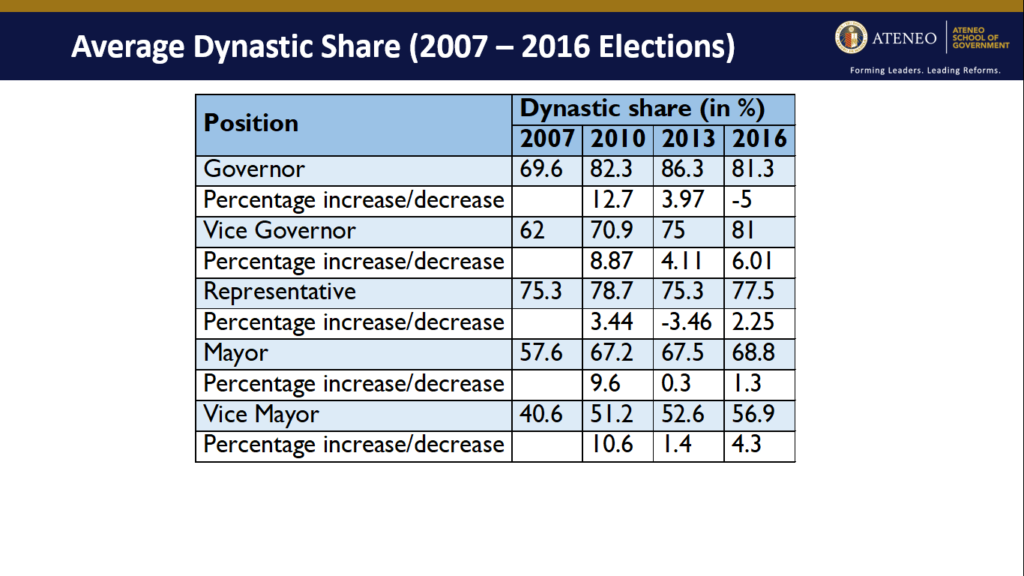

What we found, unfortunately, is that in the poorest provinces, you can have a fat dynasty finally fading and being replaced by let’s say the voters, but they don’t have alternative choices on leaders primarily because there are bigger structural problems in the Philippine scenario where you have weak political parties and even if you did have an alternative leader stepping in, these leaders would essentially not have an infrastructure to support them on the alternative path so they would be a single leader in this province basically looking at a landscape where 78% of congressmen are dynastic, 80% of governors are from political clans, something like 67% of mayors are also from political clans.

Image courtesy Ronald Mendoza

So, with that kind of a situation, if you’re aspiring to be an alternative leader, you’re not from a political clan, you happen to have a compelling message to voters and so you got in and won, it’s very easy to imagine that these types of leaders will not necessarily be so effective or that they will quickly think to basically protect their reforms that they will need to play the same game and create their own political clan or political dynasty.

So that is what we have seen actually. Is that most fat dynasties are replaced by middling dynasties who then become fat also and go through this impunity process until the voters actually want to throw them out again or that they have done something so horrible and abhorrent that the law eventually catches up with them. But the replacement is another potential fat dynasty. So, it’s really a structural problem more than sort of looking at individual families because it’s just a merry-go-round of essentially different families but playing the same game.

So, until we fix those deep-rooted structural problems in our democracy, we do not have strong political parties, we have a lot of poverty in the countryside, we have citizens who are used to patron-client relationships because they cannot find jobs, they did not have enough education, they grew up essentially with no social protection, so the state was never there to protect them, to help them, so they grow up basically looking for help from the local warlord or the local politicians, who also tend to be strong on the economic side because they have the control over land, they have the control over economic resources. So, that sort of perpetuates this really bad cycle of governance, lack of poverty reduction, lack of opportunities, which then sort of generates, keeps on generating this merry-go-round of political clans.

NC: It reminds me of the introduction to political sociology that was taught to us, that this is really—the dynasties are just natural evolutions of the combination of the Spanish caciquism and American electoralism. You blend a system of the economy that’s concentrated to a few land owners and then you bring in electoral democracy to the picture and what do you expect? Dynasties are like the natural outcomes of that. But I guess we have to update the source of wealth of political dynasties. You did mention land and natural resources. Any other source of income that’s kind of—

RM: Oh, there are many.

NC: —concentrated and that’s why they can continue the political machinery that makes them resilient among different elections over the years?

RM: In fact, there is a degree of sophistication now on the economic base of some of these political clans. It has definitely evolved over time. Whereas, the old clans may have been acting like warlords, grabbing land and cutting down timber and basically exercising a degree of impunity at the basic traditional level. The dynasties that we are seeing in today’s Philippines, are much, much more sophisticated in that you know, they could actually be big time businessmen also in construction, they can also hold assets in the modern Philippine economy. They could have many links through their relatives or through partners through different industries such as mining, such as energy.

So, these kinds of links to some extent reinforce our concern that there’s a degree of state capture to the extent that industry actually and politics are so melded together in ways that are not so good because the public good, the common good is supposed to have been represented by that vote, right? And that’s why you wanted that leader to step in and act as the regulator, act as the public sector.

But these kinds of links, there’s very little talk of conflict of interest and yet you have legislators talking about sectors that they have interests in. So, I think these types of modern day economic bases for some of these clans are really part of the problem for a country like the Philippines where our economy zoomed ahead but our political maturity and the maturity of our political institutions are actually not so mature. So, these need to mature and catch up to our 6-7% growth in order to prevent the kind of instability that we’re constantly seeing where we would like to elect leaders who are much more accountable, we would like to, you know, leaders who did something wrong, we want to put them in jail and you know make them accountable for what they’ve done but we have never been able to successfully do this.

And unfortunately, this is sort of the narrative from Ferdinand Marcos until now at least. But maybe it could actually go even further back. But in people’s minds right now, they’re looking at the promise, for instance, of the EDSA Revolution that overthrew the dictator. But in the words of a good friend of mine, Alex Lacson, who’s a well-known reformist, he said, “Well, we threw out one dictator in Malacañang Palace which is the seat of government, seat of power, but we replaced that person with many mini dictators in the different provinces.”

So, to a certain extent, we have actually debilitated that one dictator’s power, but it was quickly captured not by the people in the different provinces but by the local political clans. Captured that power, captured the control over public finance and sort of pervade this into more family members getting elected and possibly even more control over the economic sector.

NC: So, how does that explanation speak to the rhetoric of Imperial Manila? If we have mini dictators all over the country and everyone saying Manila is too powerful, so how does that speak to each other?

RM: Now, that’s a very interesting question. And my explanation of this is that Imperial Manila has one—at least one big power which is the 3 trillion budget that Malacañang has control over. And it’s well-known that 80% of this budget is actually pretty much controlled by the national level agencies like Department of Health, Department of Education, and all that. So, once you win Malacañang and you become President of the Philippines, you basically control 80% of 3 trillion pesos which you can now allocate to the rest of the country. Or at least in many ways influence at least part of the allocation.

Twenty percent of 3 trillion is actually mobilised by the local governments. The aspiration of the 1991 Local Government Code was to increase this over time so that they can pretty much be independent and in the words of the economists, fiscally independent. You don’t need the favour of that occupant in Malacañang to build your school or to build you port, or to you know have more ambition for your development plan. But now, because that part of the development has been retarded, many local leaders, every time we elect a president, we call that president essentially a winner-take-all president. The local leaders need to collaborate with this president and get part of that 80% of 3 trillion. So, that’s what makes Manila imperial.

What makes Manila not so imperial is its control over the accountability of many of these political clans that essentially have a lot of power to the extent that they can transform that capture of a province to votes. So essentially that’s the big bargaining chip that they have with Imperial Manila is that every 3 years when there’s an election and you want a national-level leader elected, whether that’s a senator, that’s a vice president, or that’s a president, you don’t make alliances with political parties. That’s essentially meaningless in the Philippines. You make alliances with political clans that hold 3 of the 5 mayors, the congresswoman, you know, the governorship. They are the ones who can actually, you know, translate that into votes.

NC: So, it’s not purely rhetorical when people say, “When you talk about Philippine politics, you don’t talk about which party is in power but you ask which family is in power?” Is that purely rhetorical or that’s pretty accurate to say?

RM: That’s pretty accurate. That’s unfortunately accurate. Our political parties coalesce around personalities rather than ideology or some kind of policy reform agenda.

So, that actually makes the policymaking agenda quite unpredictable and uncertain as well. So, that is actually what also in part keeps the development trajectory constrained because of the lack of coherence and continuity across administrations. So, until we check that, until we implement some deep reform to correct that part, we can see a lot of this uncertainty and we can see a lot of this volatility with every new president that we get. Quickly, the congressmen, quickly the local government officials rally around this new leader, with very little appreciation of the reform agenda this new leader will really represent. And so suddenly they can be supporters of federalism even though they have never championed federalism in their lives. So you have those kinds of really odd and awkward adjustments. But to be fair, it’s not just this administration. It’s actually a pattern that we’ve seen in the past.

NC: Right. Well you mentioned the F word, I would be remiss not to pick up on that. Federalism. How does that speak to patterns of political dynasties in the Philippines?

RM: Yes, well… my views on this are sort of mixed. Because the present discussion on federalism in the Philippines as a deep structural reform is if you look at the 1991 Local Government Code—this is my basic sort of understanding of how federalism can actually help. It’s—federalism could be a deeper and more correct form of that decentralisation to the extent that we can now correct for the things that we were unable to include in that reform that was introduced in 1991. So now, the president convened the committee to review the 1987 Constitution and their first decision was to implement dynasty regulation as a self-executing part of this potential new constitution.

NC: What does that mean, self-executing?

RM: It means essentially you don’t need to pass it to parliament to define what a dynasty is. And if you don’t do that, then essentially, you’ve controlled that governance pattern. Which is what we really needed to do in 1987.

So, that’s their first big decision and I think they are in the right direction as far as taking into consideration the things that went wrong so if they look at political party reforms, if they look at other things that can be improved, that could be a powerful sort of new platform for the democracy.

Well, there’s a lot of promise that federalism might be part of the solution and I think actually if you just think logically, that it might be a deeper form of decentralisation. There are many things in our attempt at decentralisation that we might be able to correct with federalism if done right. But the big challenge with the federal initiative is that you essentially need the same people who are standing to lose from this big reform to actually decide on the very things that might debilitate their concentration of political power. So, that’s really the catch-22 as far as the federal reform is concerned. So, there is talk of a constitutional assembly, con-ass, and if that is put together and that is definitely going to be dominated by political clans, it’s very difficult to imagine that they will commit—in the words of some, political harakiri. How will they sort of debilitate their own ability to keep themselves in power.

NC: How can people with power give up their power? (laughs) It doesn’t make sense.

RM: Yes. Although I would give credit to some of the political clans, particularly the younger members who are now thinking of you know, legacy for their political clans. And so, they have been part of this—I hope growing movement to try and bring better politics to the Philippines.

But I think there’s still a good number of really old thinking officials. And so, my belief is that it cannot be a constitutional assembly. It must actually be an elected group that will eventually put together that amendment to the constitution or the new constitution. But I think even if it does not progress with the Duterte administration, this talk about federalism—and to give due credit to President Duterte, who is the first mayor from Mindanao, one of our poorest areas in the Philippines, to actually become an occupant of Malacañang—he has opened the door for discussing many of these things that plague our democracy and if it were to really be a good evidence-based discussion and debate on how we are governed and how we mature as a democracy, then I think it’s a good thing.

NC: Right, and aside from federalism, of course, as an option, there are other reform agendas on the table. Pick two of your favourites.

RM: Well, I’m a big advocate of human capital investments. Investing in children and mothers. I worked in the United Nations, I worked in UNICEF as you know and one of our big advocacies, in whatever country that you may operate in, whatever level of development, the investment in children is really the investment that has the highest return. Now, this is on the economic side and maybe on the family side. But I would argue that there are political returns to investing in human capital as well, investing in children. Because over time, if you are making these young people and these families who would have been trapped in poverty without these types of investments, public investments, in their education, in their health, in social protection, they would have gone to a patron. They would have fuelled that traditional politics even further.

And so what the state can do as an alternative to you know essentially putting in place dynasty regulation, is over time, weaken the source of their power, source of the concentration of political power in a democracy, which is people who are dependent on powerful groups, powerful politicians.

So, I think job creation, investing in education and health, strengthening social protection, the very same things that traditional politicians actually do not like—they have actually fought against the social protection system introduced in the Philippines in 2009, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (conditional cash transfer program) and part of their argument is that they are better equipped to tell who is poor and who will actually receive the help. Now, this is a potential conflict of interest for some politicians because what we’re essentially trying to do is to debilitate their hold on power by actually lessening the number of poor and low-income poor in their provinces so many of them understand this and have actually fought actively against this type of social protection system.

But over time, when you protect cohorts of children and young people, and you eventually have a stronger middle class, which is really where your alternative leaders will come from. And the voters who can actually take a stand and essentially vote with their conscience and vote really with their true preference instead of voting for utang na loob (debt of gratitude) or voting for the politician who helped him or her when they needed money, when they needed some help. That should be the state actually providing that help. That should be the state ensuring those public investments. And when those investments are strong, and when your middle class is strong, then you actually have a chance of—a degree of change politics taking place at that micro level.

Of course, this will take time because you need to protect cohorts of children growing up so a baby born today under the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program will take 17, 20 years to enter the labor force. And by then one hopes that this baby would have had strong education, strong health, a different mindset on what his or her expectations will be on the democracy, on the fairness of our economy, on the inclusiveness of the economy, and also the ambition of this young Filipino in terms of the kinds of leaders that he or she will support.

NC: Right. So, I guess the idea is if I were from an impoverished family and I want to go to a health center, I don’t have to go to this congressman or to this mayor to ask for favors so I can go to a hospital. I can just go to a hospital. And these are kinds of institutional reforms that can be done from the perspective of bureaucrats? From the perspective of technocrats?

RM: Right.

NC: That can cut the influence of dynasties and their capacity for patronage.

RM: Right, exactly. And I mean it’s not really well talked about but that’s I think part of the goal of creating these types of institutions. In some places in the country, without the social protection system, there is only the local mayor they can run to. And the local mayor also happens to be the owner of most of the land or the owner of most of the businesses, the wealthiest person in that area. So it’s that kind of backwardness in the politics that will also reflect the backwardness in terms of the economy itself.

And so what we are trying to do is break both of those concentrations of power, create jobs, create a thriving economy, reduce poverty, strengthen human capital so that young people can have a stronger say. And when that happens, then you can have the possibility of change politics.

NC: Right. We’ve covered so much in our discussion but I think I want to give you as well the space to clarify other misconceptions you think that are often discussed about political dynasties.

RM: Well, we’ve been left with the task of trying to show that political clans and political dynasties are actually negatively impacting our development and we have published research on this.

But I always hasten to add that even if we did not prove this, even if we did not show that fat dynasties actually cause more poverty, more underdevelopment, even though that is not there—let’s pretend for a second that is not what the evidence says—I have to think that all the young people in the Philippines want to grow up in a meritocracy, want to grow up in an inclusive democracy where their voice actually matters, where you may be a young person but you can aspire to be a leader in the country. Rather than growing up with the son or the daughter of a congressman and expecting that this son or daughter will be the next congressman or will be the main choice for leader in the future, that kind of leadership is neither inspiring nor ambitious.

And I have to think it’s not matching the ambition of our young people, it’s not fair, it’s not drawing on our best and brightest, and we are a country known for really good managers, good doctors, good health sector professionals, we can be known for good leaders also. And so that degree of unfairness in and of itself I think justifies that we try to level the playing field here.

The other message I have especially for our leaders, and especially for our younger leaders, the second or third generation political dynasty, my message to them is no one will prevent them from running for office. You can imagine that this is essentially our choice for leaders it’s like we are in a crossroads, in an intersection but we don’t have a traffic light, we don’t have a stoplight, so it’s the bigger cars that are able to go through the intersection and bully the smaller cars. So, in that kind of a system-less sort of approach to leadership selection, it’s the more powerful, the more moneyed, the more connected that actually are successful.

What we’re trying to do here is not prevent any Filipino from running for office, no. It’s just to put some order in that running so that more young people can run for office and more young people can be considered for leadership positions.

So the message to the political clans is—because some of them have responded, “Well, you’re preventing my grandson from actually running for office also and he may be a better leader than someone who is unknown.” No, that’s not true. Actually, everyone, the idea is that everyone will have a chance, or a better chance at being considered and that this process of selecting leaders will be a fairer one. So just like putting a stoplight where more people can go through the intersection, that’s what dynasty regulation is supposed to produce.

And in the end, I agree with some of our analysts when they say that the dynasties are actually just the tip of the iceberg. There are many other challenges. A non-inclusive economy where many young people don’t get jobs. A political system that doesn’t have strong political parties. So, there is not a system that supplies the alternative leaders that actually looks for them and develops them.

So, there are many other things that we need to do besides dynasty regulation, but I have to think that dynasty regulation needs to be part of the mix at this point because it has gotten so bad. The concentration of power in Congress, the concentration of power in the different provinces in the Philippines is such that we really need to put a stop to it. And the amazing and interesting thing about this discussion now in the Philippines is that even the political dynasties—in fact, the younger ones, recognise the need for a change in our political system, an inclusiveness that actually legitimises their chance at being leaders as well. I have to believe they are not happy to be considered in history as someone who led just because of their last name. They want to be known also for their good leadership skills, for their good technocratic skills. In a system that actually favours that and still gives them a shot, actually legitimises the fact that they were actually good leaders instead of what we have now which is essentially we have really bad leaders who still get in primarily just on their last name.

NC: I love the optimistic tone of that. Unfortunately, time is not on our side and we need to wrap up the discussion. So, in summary, Ron, could you tell us whether this impression is correct? Political dynasties engender poverty.

RM: Yes. In fact, it engenders not just income poverty, but a poverty in our politics, poverty of competition, a poverty of ideas, a poverty of ambition among our young people and among our citizens that we really need to put an end to because if you have a system that actually strengthens the traditional side of our politics, the politics that actually is less accountable, is less ambitious, is not changing the deep structural problems of the country, then it’s an even deeper poverty. If you have young people who do not ambition to lead.

Image courtesy Ronald Mendoza

I always give this as an anecdote. In the United States, when you ask a kindergarten class, “Who wants to be an astronaut?” “Who wants to be a politician or a president?” A few kids will still raise their hands and say, “I want to be the President of the United States.” If you ask that in the Philippines today, you will not have young people ambitioning to be congressmen or mayors. This is reserved for the powerful. This is reserved for the wealthy. This is reserved for the children of politicians. And so that kind of poverty is even deeper than income poverty, I think. It’s a poverty of ambition and it’s a poverty of fairness that many young people will grow up thinking that that’s actually right. And that, I think is not worthy of our generation right now. We can put an end to that.

NC: Associate Professor Ron Mendoza, Dean of the Ateneo School of Government. Thank you for joining us!

RM: My pleasure.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss