The Indonesian media worked itself into a mild frenzy when it spotted Prabowo’s ex-wife Titiek Suharto and son Didiet at last week’s presidential debate. Photo credit: indonesiakatakami.wordpress.com

As strange as it may sound, an election year injects a lot of love in my marriage. When my now husband and I were still dating in 2004, we voted for the same guy in the country’s first direct presidential election. In 2009, we both voted for the same party in the the legislative election, and for the same guy again as President in 2004. This year, after countless hours spent stalking candidates on the web and lamenting the state of the country’s political parties, we decided to vote for a young male candidate in the legislative election, with some, but relatively little, consideration to the party that he was aligned with.

In this way, we are prime examples of Indonesia’s swinging voters, in that we have no particular sense of loyalty to any political party in Indonesia. Yet, it is comforting to know that we have been unified, as a couple, in our political choices over the past 10 years. As the most polarising presidential election in the voting history of my birth cohort looms closer, this idea that we share a cohesive political identity in our marriage is becoming even more important.

Social scientists have long been intrigued by the tendency for husbands and wives to share similar characteristics in religion, class, education, and age. But couple’s voting behaviour is an element of marital homogamy that has not been extensively researched in Indonesia. Considering the idea that the family is a place where politics are shared, it is interesting to see the extent to which husbands and wives voted for the same candidates or political parties in this round of the Indonesian election.

To love and cherish from this election forward until death do us part… Husband and wife, Mita and Reza’s election selfie taken on election day in Cempaka Putih, Jakarta.

A quick chat to fellow Indonesian couples who voted back in April at the polling booth in the Indonesian Embassy in Canberra suggested that the majority of couples had ‘consistent voting’ going on. In part, its being overseas votes that compounds the vote coupling.. Living in Canberra means that we get little campaign exposure for the legislative election relative to what would happen if we had been in Indonesia. There were no TV ads nor gumtrees decorated with placards brandishing the face, names, and impressive academic titles of candidates. The only placards I saw this year were just those laugh-out-loud ones that made it to the #campaignfail posts in my Facebook feed. In my case, and that of the six other couples that I talked to, the family was indeed the place where voting decisions was most discussed. In conjugal beds across the world, I imagine that many versions of this tender phrase were voiced on the eve of the legislative elections: “Jadi kita milih siapa nih, sayang?”

Of course, I have no data to back up my speculations. But as intrigued as I was, I decided to quickly look at the only dataset I have to hand that can provide some insight on couple voting behaviour in Indonesia. The 2010 Greater Jakarta Transition to Adulthood Survey is a representative sample of 3,006 young adults aged 20 -34. I looked at a sub-sample of married respondents who reported that they and their significant other voted in the 2009 election.

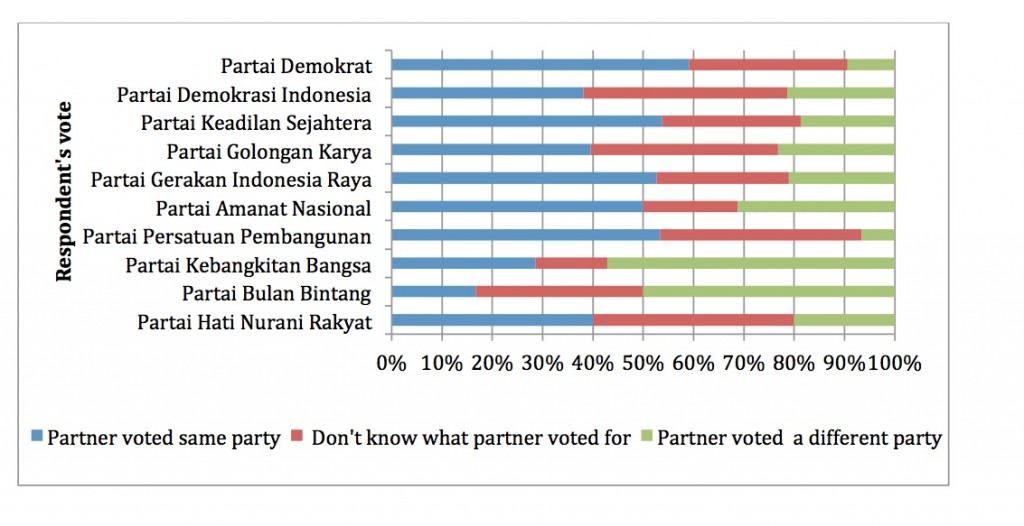

Figure 1: Partner’s voting behaviour by respondents’ party vote in the Indonesian Legislative Election 2009. Source: Greater Jakarta Transition to Adulthood Survey 2010.

Indeed, the data supports this idea of consistent voting between husbands and wives. Of the 1, 004 eligible respondents, 55 % reported that both he/she and partner voted for the same party. 13% cent reported that their partner voted for a different party, and another 32 % did not know which party their partner voted for. Partai Demokrat was the party with highest number of ‘consistent couples’ (59%). Among the top 10 parties voted by the couples, Partai Bulan Bintang had the lowest number of consistent couples (17%). Overall, the data showed that 7 in 10 respondents in voting couple households knew what his/her partner voted for, and that the majority of couples voted for the same party in 2009.

With limited data, it is still a stretch to conclude that voting is likely to be a joint-decision among Indonesian couples. At least, we can argue that marriage is indeed an important place for conversations on voting decisions. In my case and the six couples I talked to at least, marriage is a social space for husbands and wives to learn from and influence each other’s political participation, preference, and identity.

But, in looking at consistent voting, we face something of a chicken and egg problem. Are voting preferences, like religion and education levels, significant in the mating selection process? In other words, when we look for a mate, do we look for one who has similar voting preferences? In Indonesia, the problem is made more complex by the weak ideological leanings of political parties in our young democracy. Of course, I am making an exception for a certain Islamic party who reportedly actively advocates matchmaking among its cadres. But, leaving the lack of clear ideological cleavages aside, these last few weeks in the Presidential race had been intensely polarising indeed. As such, for those seeking to enter a serious relationship, I wonder whether – “Kamu pilih Jokowi atau Prabowo, sayang?” – will be the make or break question among courting couples.

Stretching the question a bit further, I wonder whether for singles, the pool of potential dates has shrunk considerably in these last few months, and is now limited only to those who share the same preference for the next President of Indonesia. Surely, this is a fantastic time for a pilpres–induced romance among newly dating couples who share the same voting preference: “fighting for a cause we both believe in” and all. But what do you when when your Facebook picture has an I stand on the right side Twittbon, but the guy you have a crush on is standing on the other side?

Ariane Utomo is a social demographer at Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific. Her latest publication on trends in spousal age and education gaps in Indonesia can be accessed here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss