Julia Mayer reports from the remote frontier town that is keeping alive the dying days of Cambodia’s murderous Khmer Rouge regime.

Cambodia’s Anlong Veng today is a dusty bustling provincial town with the odd paved road, flourishing traditional markets and a plethora of mobile phone shops offering the latest Samsung Galaxy at a fraction of the ‘real’ cost.

Anlong Veng is better known as the last stronghold for the ousted and eventually outlawed Khmer Rouge (KR) regime, which at its dictatorial peak between 1975 and 1979 was responsible for more than a quarter of the country’s population perishing as a result of execution, starvation, disease and overwork. Now, this one-time remote and mysterious frontier village is home for many Cambodians who have opted out of their lives in the urbanising centres of Phnom Penh and Siem Reap, to seek their fortunes in a transforming township.

‘‘I came here to work at the casino a few years ago. When I saved enough money I decided to open this shop,” says Sopheak as he reloads the top-card into my legitimate last year’s model phone. “I am from Phnom Penh and when my children are older I hope to return because the schools are better there.”

Atop the Dangrek escarpment, 10 kilometres from Anlong Veng, Sopheak’s phone shop is one of half a dozen on the Sa Ngam-Choam border. It sits nestled between a tailor and a sundry-store, also owned by Cambodians originating from as far away as Kampong Cham and Kratie. Thai tourists, many of whom are gamblers ambling their way toward the refurbished 10-storey swinging hot-spot, the Sangam Resort and Casino, are their main customers.

Directly opposite the casino down an ochre-hued track, are the unremarkable remains of Pol Pot’s funeral pyre preserved under a hot-tinned roof, rusting. I was informed by several locals that many tourists come to see the very place where the body of Brother Number One was unceremoniously dumped upon an old mattress elevated by rubber flat tires and ignited in 1997.

“Lots of Westerners, and many Japanese and Koreans go there,” one local told me. Yet on all occasions visited, I was the only person present, save for the young girl whose family lives next door to the site who demanded $US2, the exact going rate for foreigners visiting Ta Mok’s main ‘town’ abode which is now a museum.

The memory of Ta Mok, Brother Number Five, also known as ‘The Butcher’ for having orchestrated the mass killings in the Southwest Zone from as early as 1973, is well-preserved by the locals who continue to champion his post-regime achievements of building roads, a hospital and a school. He is also widely remembered as a benevolent brother, the gracious grandfather who handed out cash and rice to half-starved loyal combatants and civilians as the party began to spilt by the mid-1990s.

Ta Mok, who died in 2006 in custody at a military hospital in Phnom Penh before his day in docks at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal could be realised, is also memorialised by an ostentatious Angkor-inspired mausoleum in nearby Tumnup Leu village. Buried rather than cremated because it was said that he had ‘Chinese blood’, his family chose to follow the less frequently practiced tradition of the rural Chinese. Just as in life, Ta Mok defies death, most of all deaths of tens of thousands, remaining on his own, forever an exception.

While the general assumption can be made that many would prefer not to memorialise Pol Pot, the KR’s supreme leader during its darkest period, a sharp contrast in the public memory between the two senior leaders is startlingly apparent to the visitor.

Ta Mok remains a local hero, his enshrined remains are thought to bring good luck and fortune to the people of Anlong Veng. Pol Pot, on the other hand, is considered mostly irrelevant, except to the occasional foreign history buff squaring him with Stalin, Hitler and Mao, and the odd local resident who believes that his spirit has the power to reveal next week’s national lottery numbers.

Preserving perpetrator sites for purposes of reconciliation is a touchy subject at best, especially with regards to its effectiveness in healing the wounds of the past still felt very much in the present. The pressure to be on the right side of moral history often means that the past is further reinforced by the polarising terms of ‘perpetrator’ and ‘victim’, when in the majority of cases, such distinctions are commonly blurred.

Following a 20-year long civil war, it appeared that the Royal Government of Cambodia was well aware of the dilemmas posed by memorialising the dying days of the Khmer Rouge, and began to made loud noises about how memorialising their past was critical to the peace process, whilst simultaneously asserting their victory.

In 2001, Prime Minister Hun Sen ordered a ‘circular’ regarding the ‘preparation of Anlong Veng to become a region for historical tourism’. Delivered literally in the form of roundabout marking the end of the then rugged Route 67, the gaudy pyramidal centrepiece framed by golden mythical snakes holding a globe, a bird and a startled deer, still eclipses most other surrounding buildings today. Answering to the government’s clarion call of the Anlong Veng District being of ‘historic importance in the final stage of the political life of the leaders and military organisation of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge’, the Ministry of Tourism in conjunction with the local authorities excited to make a few fast tourist dollars, then set about erecting signs deemed of significance with wild abandon.

“Ta Mok’s House Historical Attractive Site”, reads one dilapidated sign of translated tortured expression. The house itself initially comes as a surprise for the irony of being a perpetrator’s modest hideout with an exquisite view. On signage that have seen better days, possessives get a little out of hand as if the ownership of past crimes against humanity belong to neither a group of perpetrators nor is the singular responsibility of one: “Pol Pot’s was sentenced here” and “Pol Pot’s was cremated here”.

In 2003 rumours further circulated about the intention to create a ‘Pol Pot theme park’ where the ruined homes of Pol Pot and other Khmer Rouge leaders, including their offices and munition warehouses were to be rebuilt, and would be accompanied by a museum and a theatre in Anlong Veng. Unsurprisingly, the suggestion met with substantial outcries regarding the ‘Disneyfication’ of a highly contentious area. The majority of plans were temporarily cast aside until 2006 when former S-21 ‘Tuol Sleng’ mug-shot photographer Nhem En, who had defected from the Khmer Rouge in 1996 and later became a deputy governor of the district, started to voice his trademark capitalist optimism, stressing how tourism would yank Anlong Veng into the 21st century. In 2010, further promises were made to turn Anlong Veng into a Tourism Zone.

But nothing much happened.

This happened partly as a result of disagreements as to how the past should be remembered, but mostly because people quite simply lost interest with each and every peaceful passing year. Tourist dollars, it seemed, could be better earned as a gambling town or as quick stopover on route to Preah Vihear, now completely within Cambodian territory.

It is as if the local authorities had somehow missed the boat across Ta Mok’s man-made lake to capitalise on dark tourism, but such delays are now seen as advantageous by the Sleuk Rith Institute, which has been organising Anlong Veng Peace Tours as part of a community initiative since 2015.

The tours, conducted over a four-day period, give students from other parts of Cambodia the opportunity to participate in a range of educational activities which includes visiting 14 sites identified as being part of the Khmer Rouge past. The tours also include the chance to converse with ex-Khmer Rouge cadre and victims who continue to live in the area.

“The tour is designed to be rehabilitative to former KR cadres in that it provides both groups an opportunity to reflect on, and impart their understanding of, their experiences during the Democratic Kampuchea period and the civil war years that followed,” says Dr Ly Sok-Kheang, Director of the Anlong Veng Peace Centre which first opened its doors in May 2016.

The Anlong Veng Peace Centre, Ta Mok’s ‘historical attractive’ mountain hide-out, was almost razed to the ground by fire which had travelled up the escarpment during the 2010 land-clearing season.

“In the dry season, from December to the end of March, I do not leave the area,” says Khemara, the son of a Cambodian People’s Party army officer who has been living in the area since 1999, recalling how flames engulfed Ta Mok’s house with no help on standby. “I stay here to make sure the grass is kept short.”

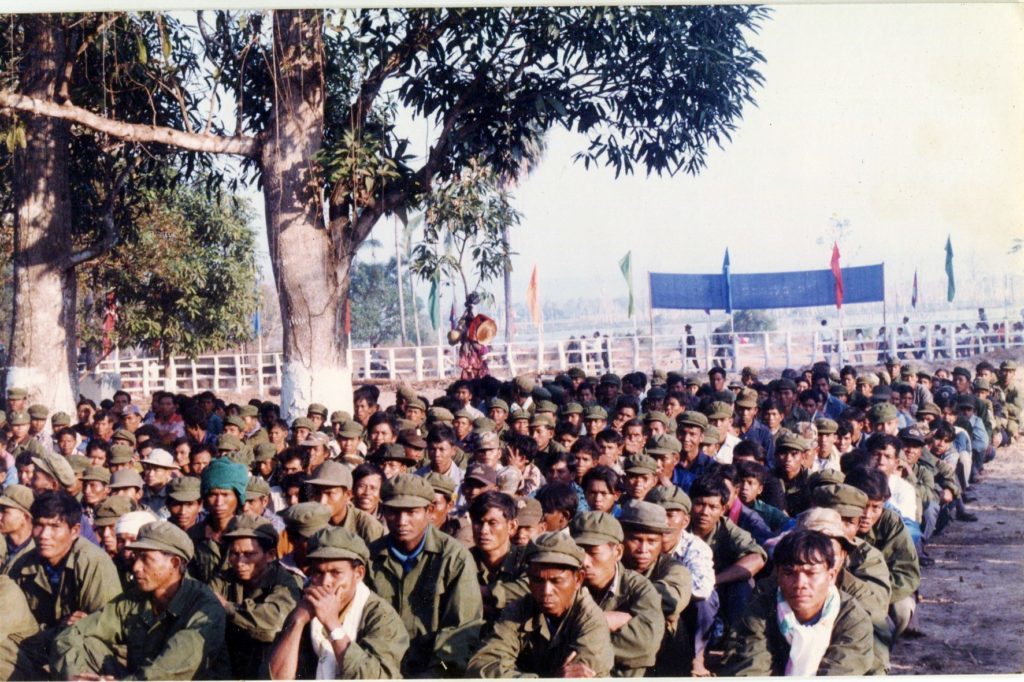

With final preservation touches yet to be made, the Anlong Veng Peace Centre is now ready to be used as a classroom. It contains a small library, a long table and chairs, and a large space devoted to circle-time discussions. Framed photographs of the Khmer Rouge combatants’ reintegration into normal society in February 1999, adorn its crude concrete walls. The look of resignation and apprehension written across the faces of young men who laid down their guns that day, is a profoundly moving reminder of those first steps toward reconciliation.

“Peace does not simply mean the absence of war, and many of the wounds of the conflict remain unhealed in Anlong Veng, and are worsened by discrimination, polarisation and misunderstanding,” said Dr Ly Sok-Kheang in a Voice of America discussion last year shared Kamboly Dy, author of a widely-read school history textbook on the Khmer Rouge regime period.

It is a pertinent point. Etched into the faces of the aging locals are still deep scars of the past, and, as the ones embedded in the landscape become increasingly less visible, it is their memories, including the survival of them, which holds the key for a more nuanced understanding about the nature of conflict.

“The local residents are the main sources for attracting visitors,” said Ly Sok-Kheng in his VOA interview. “They can participate in discussion and historical sharing with visitors. This sharing allows visitors to learn not only the history but also the beliefs and ways of thinking of the former cadres.”

The Anlong Veng District has narrowly escaped the tourist trail by default of its still quaint remoteness. But it has undeniably important work to do regarding moral and civic education for the younger generation of Cambodians who are becoming more curious about the past which increasingly sounds more fictitious as years go by.

Tackling this with the sensitivity that it deserves could well mean that the Anlong Veng District’s true calling is one in which a deeper understanding of peace and reconciliation has the best chance to prosper. Done right, that is, tastefully and respectively, it could serve as a benchmark for other places where traumatic pasts are still fraught by divisions. It could also result in a more sustainable form of tourism much desired by the Anlong Veng District, a place one can truly call ‘home’ by the likes of Sopheak who continue to seek better lives for their families.

Julia Mayer is a Masters of Museum and Heritage Studies student at the Australian National University. She has lived in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and South Korea, and has written extensively on traditional arts, performances and cinema in the region. She is also the Asia Correspondent for Metro Magazine Australia.

This piece is published in partnership with Policy Forum – Asia and the Pacific’s platform for public policy analysis, opinion, debate, and discussion.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss