Writing about classical Angkor civilization seemed like a straightforward business: do the research, get it critiqued, publish a book. But scholarship on Angkor, and indeed on much of pre-modern Southeast Asian history, is accelerating. That has made Angkor a much more dynamic subject, albeit one that is also harder to write about. Silkworm Books published my effort, The Story of Angkor, this summer. It’s a slim volume aimed at visitors and armchair historians. It is not based on primary research; rather it brings a popular touch to a cool subject that is, unfortunately, rendered dry by almost everything else available on the market.

The story behind the story, however, is the revolution in Angkor history. Most sources available today are more or less based on the arguments laid out by early 20th century epigraphy and archaeology. The granddaddy of Angkor studies is George Coedès, who published in French in the 1940s, and whose works were translated into English in the 1960s, in time to influence the budding scholarship on Southeast Asia that emerged in the United States.

Coedès defined the paradigm. He argued that Southeast Asia represented a ‘Farther India’, a land of gold that was conquered and colonized by waves of Indians from around 200 BC through 400 AD. His work also gave us the basic timeline of the kings and therefore the monuments. He helped lay out a narrative of a pre-Angkor Cambodia trapped in a dark ages. He and other scholars documented wars between the Khmers and the Chams that defined the rise of Angkor’s first Buddhist king. The shadow of Coedès stretches so long because the Khmer Rouge, Vietnamese invasion and destructive poverty have kept international scholarship at bay. Only in the 1990s did meaningful work on Angkor resume.

Although we remain deeply in Coedès’ debt for his tireless work on translating inscriptions and defining lines of kings, his interpretations are being picked off, one by one. Today while his research remains relevant, his conclusions seem fanciful. There is no clear answer to Indianization. Most scholars today argue against the idea of Indian colonizers, although one oddball Brahmin sect, the Pasupatas, which were willing to mix with lower castes, may have settled in the region. But others suggest that Indian ideas came from Malays and other travellers visiting India and Sri Lanka, rather than from Indians actually settling in Southeast Asia.

Coedès’ idea of the origins of Angkor have also suffered. He believed an early Khmer-speaking civilization grew up around southern Vietnam, based on a port called Oc Eo and a nearby city called Angkor Borei. This fell into disunion and chaos, and was assaulted by enemy invaders, perhaps from Champa or Java. There is no evidence to back this up. The evidence is going the other way, actually: the epicentre of Funan may have not even been where Coedès believed, in fact being placed further west in the Menam Basin. There is growing evidence that pre-Angkor sites were prosperous and dynamic, with hundreds or even thousands of temples and other archaeological remains now identified. The accepted foundation of classical Angkor, in the year 802, now looks less radical and more in keeping with an existing culture.

Indeed, it seems that the first version of classical Angkor building, at a site called Roluos, was not even the main event. This year, scholars announced the discovery of a city, Mahendraparvata, on Mount Kulen, some 50 kilometers distant from Angkor. This area was the source of river waters and of quarries for the beautiful sandstone used for Angkor’s monuments. But the mountain was actually encompassed by a dense urban centre that was linked to Angkor and other surrounding areas, creating a vast urban civilization on par with the biggest pre-industrial societies of China or Europe. Although my book discussed this sprawling nature of Angkor, the discover on Mount Kulen came too late for my book, as its existence and excavation was kept secret among archaeologists and Cambodian authorities.

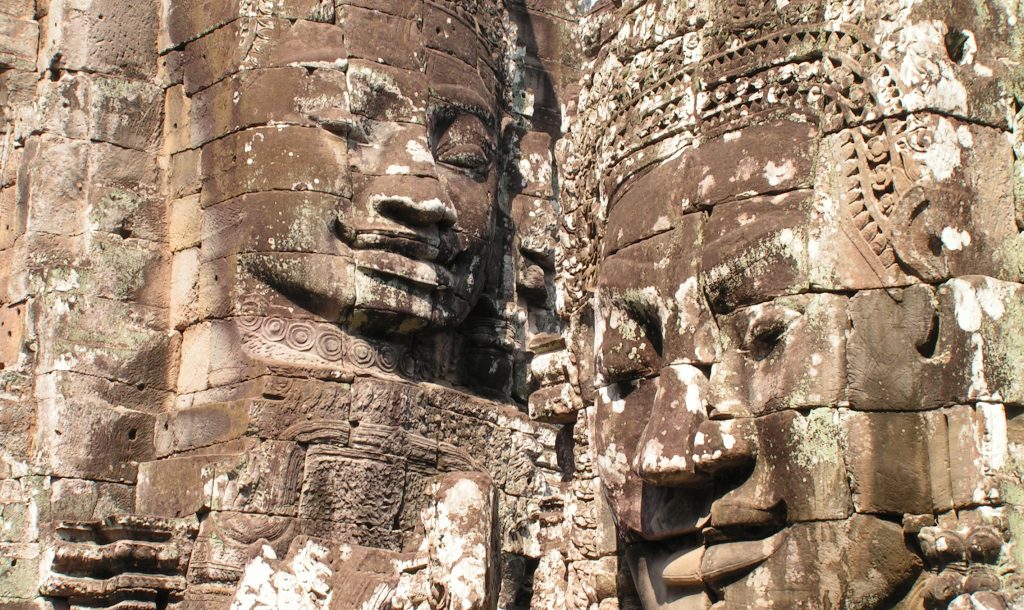

The final big change to the Coedès paradigm is around the elevation of Angkor’s first Buddhist king, Jayavarman VII. Coedès recounts a war between the Khmers and the Chams; the Chams used a water-borne sneak attack to raze Angkor, discrediting the ruling Hindu castes and allowing the rise of Jayavarman VII. But many scholars have discredited the whole thing. There was strife but it was between factions of both Chams and Khmers, more like a civil war than a war between nation-states. The battles on water, supposedly portrayed in reliefs on the Bayon, never happened, and the reliefs have been misinterpreted.

Even the dating of the Bayon and Angkor Wat are now under fire. The chronicle of Zhou Daguan, a Chinese visitor in the 13th century, makes so little account of Angkor Wat that some scholars question whether it was even built until after Zhou’s visit – which would completely upend our understanding of it. So the story of Angkor turns out to be far more fluid than the stone remains suggest, and the history of pre-modern Southeast Asia is still up for grabs.

Jame DiBiasio is a financial journalist and editor in Hong Kong. He is the author of The Story of Angkor, published by Silkworm Books (Chiang Mai, 2013), and of the novel Gaijin Cowgirl, published by Crime Wave Press (Hong Kong, 2013).

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss