Yes, Indonesia’s mass Islamic organisations are tolerant and democrats. But no, that doesn’t mean their culture can be exported to counter extremism.

Can the solution to Islamic extremism be found in the importation of a more tolerant and democratic culture to the Middle East? This is the question at the heart of recent discussions in the pages of The New York Times, The Huffington Post, and The Boston Globe about Islam Nusantara (Islam of the archipelago).

Islam Nusantara is the name given to the theology of the world’s largest Islamic organisation, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) of Indonesia. NU supports democracy, is largely tolerant of religious minorities, and does not seek state implementation of Islamic law. Promoters of Islam Nusantara argue that exporting this aspect of Indonesian Islamic culture can provide the antidote to the disease of Islamic extremism and militant jihadism plaguing the Muslim world.

It’s an instinctively appealing idea. It’s also wrong. The idea that Indonesian culture can be exported is a fiction born of a threefold misunderstanding about NU, the barriers to strengthening democratic values in the Middle East, and the origins of Islamic State (IS).

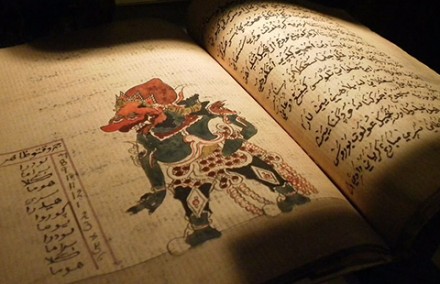

The term Islam Nusantara was coined in the early 2000s to refer to NU’s theological mix of Sunni Islam, Sufism, and local religious practices like the veneration of the nine saints of Java (the Walisongo). These practices are born out of the structure of NU.

NU is a coalition of Islamic preachers and prominent Javanese families that came together in 1926 to oppose the influence of Islamic modernism, the movement from Egypt launched by Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad Abduh and Muhammad Rasyid Ridha to strengthen Muslims through the promotion of science and a return to the foundational sources of Islam. Instead of reforming Islam, NU seeks to retain its mix of classical Islamic jurisprudence, Sufism, and local traditions rooted in the pilgrimage sites of Java.

Today NU’s opponent is still Islamic modernism as well as its distant cousin, Salafi jihadism. And despite what proponents of Islam Nusantara say, NU’s tolerance is selective.

Its tolerance of Christians, Hindus, Buddhists and Confucians stands in stark contrast to its longstanding intolerance of Ahmadi Muslims and communists. The reason for this discrepancy is that Christians and the other accepted minorities have been important allies for NU in its struggle against Islamic modernism, while communists and Ahmadis are seen as a threat to NU and the Indonesian nation.

Certainly it is important to counter the idea that Islam and IS are the same. And it is true that NU’s tolerant culture has been crucial for the success of Indonesian democracy. But exporting a partial aspect of Javanese traditionalist Islam without the institutional, familiar, or local structure that supports it is unlikely to have much influence. This is indeed why NU has not spread beyond Indonesia in the 90 years since it was founded.

NU’s beliefs are compatible with democracy. But as survey researchers have long known (and reported repeatedly here, here and here), so are the views of most of the world’s Muslims. The barriers to democracy in the Muslim world are political and economic, not cultural.

IS was born in the same conditions in which the Taliban and Hamas were born, in places where there is no meaningful political representation or political order. The prolonged civil war in Syria and failed reconstruction of Iraq created a power vacuum that IS filled.

By contrast to the situation in Iraq and Syria, an environment of sustained political engagement provided the context in which the political aspects of Islam Nusantara were developed.

In the 1920s NU’s religious theology was accompanied by a political vision for an international Caliphate and Islamic state. But Indonesia provides strong evidence that if you allow Islamic organisations to participate in the political process they will moderate their demands and become part of the system rather than seek to overthrow it.

Over the course of the 20th and early 21st centuries, Indonesian Islamic organisations like NU that have participated in crafting the policies of the state have implicitly or explicitly moderated their views.

Their leaders have shifted from being pan-Islamists who seek a global Caliphate, to Indonesian Islamists who aim to create an Indonesian Islamic State, to Indonesian Muslim pluralists who actively work with other religious and ideological groups and promise to safeguard their rights, to post-Islamists who view Islam as complementary to other ways of organising politics and society. They have moderated through participation.

While there are exceptions to this trend, most notably the “new Islamists” who generate dramatic headlines but possess little electoral or social influence, the overall trend toward moderation is clear — include Islamists in the political process, and over time their ideologies and tactics will moderate toward support for democracy. This is the opposite of what has happened in Iraq and Syria, where despots with foreign backing have coopted Islamists or actively oppressed them.

The idea of exporting a more tolerant culture is a prime example of what the anthropologist Mahmood Mamdani calls “culture talk”; the predilection to define Islamic cultures according to their ‘essential’ characteristics in order to sort good Muslims from bad Muslims rather than discussing the specific conditions under which extremist movements emerge. It is a shallow and escapist way of thinking about the problem of Islamic extremism.

An example may help illustrate the problem of culture talk. What if we turned the logic of exporting culture around? Since Britain has almost zero gun violence, and the United States has an epidemic of gun violence, perhaps the problem could be solved by importing British culture to the United States?

Such a solution may be appealing at first glance, but it’s a fanciful way of thinking about a problem that would be better addressed through normal policies. In the case of IS, that means supporting more representative political institutions and equitable economies, and reducing support for militarism in the Middle East.

Jeremy Menchik is assistant professor in the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University. His book Islam and Democracy in Indonesia: Tolerance without Liberalism, is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss