Many scholars, feminists and activists believe that addressing the lack of female representation in parliament and in political parties is a core issue in advancing women’s interests in Indonesia. As a result, Indonesia has implemented gender quotas for political parties’ legislative candidacies. The 2003 election law stated that 30% of candidates on political parties’ legislative candidate lists should be women. Many NGOs have been working hard at encouraging parties to achieve this quota, with female representation in the national parliament (DPR) languishing at 11% in 2004, 17.9% in 2009, and 17.3% in 2014.

However, the rise of identity politics and political Islam, particularly since the Jakarta election of 2017, suggests there is a new challenge for feminists and those hoping for greater affirmative action for women in politics. As a recent report from the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC) states:

“If the 212 movement reinvented Muslim political identity in majoritarian terms, it also activated women’s political agency along conservative lines: mothers must mobilize against Jokowi in order to protect their children from un-Godly communism, homosexuality, and other moral threats associated with Jokowi’s camp”.

Thus, the new challenge for feminists is located in the rise of a religiously conservative women’s movement, which works to actively challenge feminism from within the system. The 2019 election highlights the growing influence of female candidates from anti-feminist groups who have excellent leadership skills, know how to deploy clear and convincing arguments, and work extensively at the grass-roots level. Feminists must be ready to contest their narrative, as these candidates and the activists aligned with them will have an expansive influence in the policy discourse in parliaments beyond 2019.

I talked to several conservative female candidates standing in Wednesday’s election, in the hope that by better understanding this emerging form of female political participation, feminists come to acknowledge how the diversity of female candidates’ ideologies will throw up challenges for their movement in parliament.

Conservative female candidates

The role of women in the Indonesian elections is largely under-examined. Yet as I’ve written previously, the role of female canvassers and volunteers—colloquially known as emak-emak—is important in this year’s election campaign. On 24 March in Bekasi, West Java, I attended a campaign rally for Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (Prosperous Justice Party, PKS). The first thing I noticed was that women clearly outnumbered men, and they stayed under the burning sun throughout the campaign. The women’s dedication was acknowledged by the president of PKS for West Java, Ahmad Syaikhu. The ex-mayor of Bekasi said: “We are also thankful to the power of emak-emak that have been actively campaigning for the party and Prabowo-Sandi.”

While emak-emak are sometimes used tokenistically by more senior male politicians so they can say they are addressing the women’s vote, many conservative Islamist women are campaigning in new and unique ways in this election.

Sri Vira Chandra, a PKS candidate from East Jakarta for Jakarta’s city council (DPRD), is known as Umi Vira. She is an Islamic preacher and is active in organisations such as Wanita Indonesia (Indonesian Women) and Aliansi Cinta Keluarga Indonesia (Family Love Alliance, or AILA, which I will discuss in more detail below). Umi Vira has been working with women at the grassroots for 25 years. In a recent video, she explains she decided to join politics because of the underrepresentation of Muslimah [Muslim women] in parliament who understand the real issues affecting women.

While standing for parliament she continues her work as a preacher, going from one majelis taklim (Islamic study circle) to another, providing spiritual advice, teaching life skills, and empowering women according to Islamic norms. She said in an interview with me in March:

“I am not a feminist. I am a Muslimah who understands that in Islam, women have a noble place. She has the authority to give good deeds to her country, and it starts with the family. A woman has a spiritual value to uphold so that the whole family can be together in heaven. Does feminism count that? I don’t think so. On that point, we disagree.”

She has also been featured in YouTube videos intended to amplify her campaign, providing an Islamic perspective when giving lectures about parenting and morality issues, including LGBTQ people. She said in one of the videos:

“We have to make sure Indonesian law helps us to protect our children. Now we can easily buy condoms in convenience stores. Anyone can buy it, anyone, even those who aren’t yet married. They said it was to prevent HIV/AIDS, but the only thing they need to regulate is the extra-marital sex itself.”

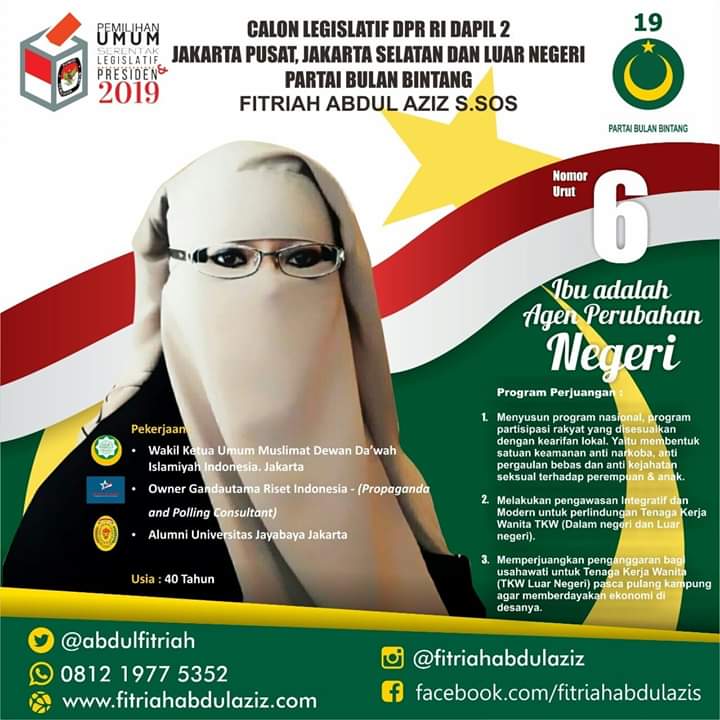

Fitriah Abdul Aziz, meanwhile, is seeking to represent PBB (the Crescent Star Party) in the DPR. She is also the vice chairwoman of the women’s wing of Dewan Dakwah Islamiyah Indonesia (DDII), a long-standing Islamist organisation, and holds an enormous amount of experience with other organisations. The constituency she is contesting covers both Central and South Jakarta as well as overseas voters. She is targeting Indonesian migrant workers working overseas, particularly in Malaysia, to win election. In one YouTube video she emphasises the contribution of female migrant workers to Indonesia’s economy, and what the government should do to protect the migrant workers. In an interview, she said:

“I don’t think it’s a good idea to let women work overseas, go unaccompanied by their husband, and leave their children behind. The government should only give working permits to men. Moreover, we don’t have an established system to protect those women from rape, slavery, or assigned to placements without sufficient skills. The Ministry of Workforce needs to prepare them before leaving the country.”

Female conservatives are using two campaign channels to win influence: majelis taklim and social media. Majelis taklim are regular, community-organised Islamic study circle that branch out to the village and neighbourhood level. Majelis taklim are open for everyone, and although they have separate groups for men and women, the women’s groups are often more active. Majelis taklim are not always political. They serve as a place for women to exchange information about their daily life and religious learning. Usually members of majelis taklim ask an ulema or religious preacher and counsellor to talk on certain topics as requested by members.

Still, the recent growth of Islamic politics has turned majelis taklim into a significant arena for political campaigning. Azizah Nur Tamhid is a PKS candidate standing for in DPR electorate that includes Bekasi and Depok City. She is the wife of the former Depok mayor, Nur Mahmudi Ismail, and relies heavily on him for campaign financing. As the head of PKK (Pendidikan Kesejahteraan Keluarga, or Family Welfare Program) and the board of Al-Mubarokah, a group of majelis taklim with hundreds of members, she has an extensive network in the constituency.

Azizah said she relies on Al-Mubarokah to secure votes. Azizah, Fitriah, and Umi Vira often approach the potential women voters through the spiritual lectures they deliver in majelis taklim, underlining the urgency of women’s participation in politics and encouraging the women to vote for them. Umi Vira, the PKS candidate for the Jakarta city council, said in an interview in March:

“I said: ladies, in majelis taklim we cannot produce regulations, we need to be involved in politics. If you want to fight for what’s right and important [and] you want to put it in regulations, you have to choose your representative in politics.”

To some extent, these women claim to promote women’s empowerment. They all agree on the right to access education, the right to work, and the rights of association and freedom of expression in public spaces. They believe that these rights are not derived from feminism, but from Islamic values, because Islam has placed women in a special position. Umi Vira believes that Islam empowers women in many aspects. She said:

“Islam didn’t prohibit women from working, but we also need to think about the family as our main base. Indonesia should be ‘strong from home’, and it’s not only the responsibility of the mother but the whole family. Women can protest if the husband doesn’t take care of the children. That’s an Islamic concept. Women have the power to transform the family and the entire nation through empowerment.”

Family resilience is their main selling point to combat the morality issues they also campaign on. They critique the concept of gender equality and bodily autonomy because, in Islam, gender is clear; it’s characterised only by two sexes, which entail inherent characteristics known as kodrat. Acknowledging gender means problematising kodrat, because it also raises the issue of non-binary genders. Meanwhile, these women reject the notion of bodily autonomy as it perpetuates things they say are contrary to Islamic values, such as pre-marital sex, legal abortion, and the LGBTIQ community.

What stands out as well among all these candidates is the use of social media to augment the in-person persuasion. Social media campaigning is important because women voters have more limited mobility. Due to social expectations that women undertake most of the domestic chores (while also working and taking care of their children), their access to information is primarily through their peers and social media. Social media is becoming a key channel for anti-feminist messages spread by women: recently, the Indonesia Tanpa Feminis (Indonesia Without Feminism) Instagram profile went viral, targeting young girls with hashtag #UninstallFeminism and promoting the message “my body is not mine, but Allah’s” to counter the feminist concept of body autonomy. It is part of a series of online campaigns by conservatives targeting the younger population, which include Pemuda Hijrah, Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran, and Ayo Poligami.

Fitria Abdul Azis, vice chairwoman of the women’s wing of Islamist NGO Dewan Dakwah Islamiyah Indonesia (DDII), who’s standing for the DPR on a Crescent Star Party (PBB) ticket. (Photo: instagram)

Shaping gender policy issues

The battleground for conservative female candidates is the new Elimination of Sexual Violence Bill (RUU Penghapusan Kekerasan Seksual, or RUU P-KS). These candidates think the bill could threaten the morality of the nation. PKS’ Azizah Nur Tamhid has said:

“The last Elimination of Sexual Violence bill ought to be rejected because it weakens the family. If this is applied, we cannot report pre-marital sex cases [to the police]. No law prohibits adultery or alcohol, but parents can be jailed [for enforcing their daughters to wear hijab]. That’s what they mean by sexual violence. They want to eliminate it; they want to be free, and they are disrupting the family values.”

PBB’s Fitriah Abdul Aziz maintains a similar stance, saying:

“Of course I reject the bill. It [RUU P-KS] enables people to engage in free sex. The title is good, but the content is full of manipulation. My programs are not aligned with the draft bill because we have a different standpoint. If RUU P-KS allows free sex, my programs will impede free sex.”

PKS’ Umi Vira problematises the root of the draft bill itself, and says:

“The RUU P-KS stems from a radical feminist perspective. Look at the terminology in the document…Just delete those terms! Don’t use ‘gender-based violence’ but ‘sexual offences’ to emphasise [that] the incident is a crime. We have sufficient laws to help women out of their misery. We don’t need new regulations. It is clear that the passing of this law would benefit certain groups only.”

Leading the campaign against the bill is the Family Love Alliance (Aliansi Cinta Keluarga, AILA), of which Umi Vira is a member. AILA was founded in 2013 by a number of Islamist organisations including MIUMI (The Council of Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals and Young Ulemas), KMKI (Muslimah Community for Islamist Studies), and INSISTS (Institute for The Study of Islamic Thought and Civilizations).

AILA conducts high-level policy advocacy on women, children, and family issues. All of the board members are women except for one advisor, Bachtiar Nasir, a Salafi leader who also played a pivotal role in the 212 Movement in 2016–17. Some members of AILA are running for the 2019 legislative election, including Nurul Hidayati, AILA’s secretary general, who is standing for the DPR on a PKS ticket in Tangerang, and, of course, Umi Vira for her Jakarta city council seat.

AILA first came to public attention in 2017, when they asked the Constitutional Court to review three articles in the Criminal Code that they claimed allowed adultery, immoral behaviour, and homosexuality. The Constitutional Court rejected their case, and the organisation has now shifted its sights to the RUU P-KS. AILA’s standpoint echoes those of the candidates I spoke to. It argues that the bill is derived from a radical form of feminism that allows homosexuality, abortion, and pre-marital sex. Furthermore, it indicates that the wife could sue her husband for practicing non-consensual sex, and parents could be jailed for pushing their daughters to wear hijab. AILA believes these laws will destroy the foundation of Indonesian families.

Another critical policy issue during the upcoming legislative period will be the revision of the Marriage Law. In response to the issue of child marriage, feminist activists are pushing to increase the minimum legal age of a bride from its current level of 16. Last year, the Constitutional Court declared the 1974 marriage law unconstitutional, and mandated a revision of the law passing within three years during the next legislative period. As mentioned in an article published by Center for Gender Studies (CGS), one of AILA’s member organisations:

“The level of maturity of boys and girls cannot be assumed. Some of them reach physical and psychological maturity at 18 while others do not. Thus, applying the same minimum age for girls and boys for the sake of ‘gender equality’ is absurd. They blindly follow the international convention without criticism. On the contrary, it potentially seizes one’s rights and does not respect the choice of women who came from varied backgrounds with different socio-cultural factors and religious norms.”

Indonesia’s elections in the periphery: a view from Maluku

The eastern islands showcase how national-level polarisation filters through to the grassroots, but also how the realities of decentralised power interfere with national-level political designs.

Preparing for a fight

Indonesia has been too focused on the presidential race, with not enough attention being given to the legislative election. Legislatures at the district and city level, for instance, are allowed to produce their local bylaws, which are often inspired by patriarchal local cultures or religious values that rationalise discrimination against women. The National Commission on Violence against Women (Kompas Perempuan) has noted that as of 2017, 421 discriminatory local bylaws position women’s bodies as a moral object, for example, enforcing curfews for women or obliging women to wear headscarves. Legislative bodies—and not just at the national level—therefore offer a strategic position for addressing women’s agendas, and the women elected to these bodies will be crucial in determining the legal dimensions of gender relations in the next period of government.

So while increasing the number of representative women in parliament is an important task, it should not be the only focus when analysing the role of women in politics in Indonesia. We also need to critically examine the implications of policies that women themselves are fighting for, and situate their political practice in today’s political climate. The push for gender quotas will not only benefit those who have clear gender equality agendas, but also those in the anti-feminist movement who represent the voices of conservative groups. As their movement is growing and influencing the public policy discourse, it may be harder to achieve the end objective of affirmative action, which is to actualise women’s rights and the protection of women in Indonesia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss