Ever since the Reformasi years after 1998, discussions on reform of Malaysia’s First Past the Post (FPTP) electoral system have taken up by scholars and activists. Important contributions by Lim Hong Hai, Donald Horowitz and Clive Kessler have explored how FPTP interacts with, and reinforces, Malaysia’s political divisions. Some have offered reform proposals: Horowitz proposed criteria to consider electoral system reform, while Kessler advocated for Australia’s Alternative Vote (AV). I joined the conversation after 2008, unpacking how FPTP sustained Malaysia’s electoral authoritarianism and communalism under the rule of Barisan Nasional (BN), the multi-ethnic coalition dominated by United Malays National Organisation (UMNO).

Within civil society groups, the cause of electoral system change found its first constituency in women’s groups frustrated by stagnation in the push for gender quotas under FPTP. Some campaigners mooted modified forms of a Mixed Member Majoritarian (MMM) system that included “Women-Only Additional Seats” and “Non-Constituency Seats”. Before the 2018 election, Maria Chin Abdullah, the then chairperson of Bersih, proposed Germany’s Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) model as a solution to encourage more diverse political choices.

But what needs to be done with the FPTP system itself after the victory of Pakatan Harapan (PH) in the 14th general election (GE14) in May 2018 remains insufficiently debated. I argue here that the problems with FPTP have become more stark than ever after GE14, such that consideration of wholesale reform of how Malaysians choose their government should be a top priority.

No “low-hanging fruit”

For many, electoral system change is a long term goal, and the more realistic short-run objective should be curbing malapportionment and gerrymandering while maintaining FPTP. This view rests on two assumptions: first, that the political and legal obstacles in the way of changing electoral systems are greater than those in the way of correcting partisan gerrymandering and malapportionment; second, that electoral system reform is an ideal instead of a necessity. The reality is that both may not be true.

Let’s first examine the first argument, regarding the legal and political barriers. Far from being straightforward fixes, malapportionment and gerrymandering cannot be corrected and prevented without some amendments to Malaysia’s federal constitution, to address three problematic provisions which have enabled malpractices.

First is Article 46, which allows the parliament to arbitrarily allocates seats across states and federal territories, and which has allowed inter-state malapportionment to worsen since 1974. Second, the demand by Section 2(c) of the Thirteenth Schedule for constituencies within the same state to be “approximately equal” is compromised by the vaguely-worded “area weightage” and the 1974 removal of a cap on maximum deviation from state averages.

Third, Section 2(d) of the Thirteenth Schedule fails to limit gerrymandering, with its weak demands for avoidance of “inconveniences” and “maintenance of local ties”, with both terms undefined. Legislation which strictly defines the four terms in Sections 2(c) and 2(d) might help skirt the need for a constitutional amendment and allow the Electoral Commission to draw fairer constituency boundaries within any given state, but no correction of inter-state malapportionment is possible without amending Article 46.

To make matters worse, the flawed seat boundaries introduced by the Electoral Commission in 2015 for Sarawak and 2018 for the States of Malaya cannot be corrected until they are ready for review in 2023 and 2026 respectively. The eight-year interval, mandated by the Constitution, may be skirted to force a new review only by amending Article 46 to add at least a parliamentary constituency to every state and territory that needs fixing. Even then, however, politics would be a barrier: states with bargaining power—especially Sarawak, now with 19 opposition votes in the federal parliament where the new Pakatan Harapan (PH) government lacks a two-third majority to carry a constitutional amendment—will demand more seats than they warrant. Mitigation of intra-state malapportionment and gerrymandering may come with a huge price in inter-state malapportionment, defeating the purpose of correcting seat–vote disproportionality.

The peril of inter-state malapportionment cannot be understated. In the 2018 election, the largest parliamentary constituency, P102 Bangi in Selangor, had 178,190 voters—about nine times of 19,592 voters in the smallest, P207 Igan in Sarawak. Even after excluding the four outliers: Sabah, Sarawak, Labuan and Putrajaya, the picture is stark: the 22 constituencies in Selangor had an average of 109,776 voters, while the 14 in Pahang had an average of 58,856. Intra-state equal apportionment will not correct the injustice between voters in Selangor, Pahang, and the nine other states and the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur.

Facilitated by Article 46, from 1965 to 2005 the size of Malaysia’s parliament grew like a teenager from 144 to 222 seats, and inter-state malapportionment simultaneously worsened, thanks to two flawed practices. First, there was no transfer of seats from demographically-shrinking states to the growing ones, so that no incumbents would lose their seat. Second, the numbers of seats was increased to reduce the burden of constituency service for parliamentarians in populous states—but this process disproportionally benefited the government’s stronghold states regardless of electorate size. Any proposal to add seats in order to open the door to early redelineation is bound to deepen, not lessen, the problem.

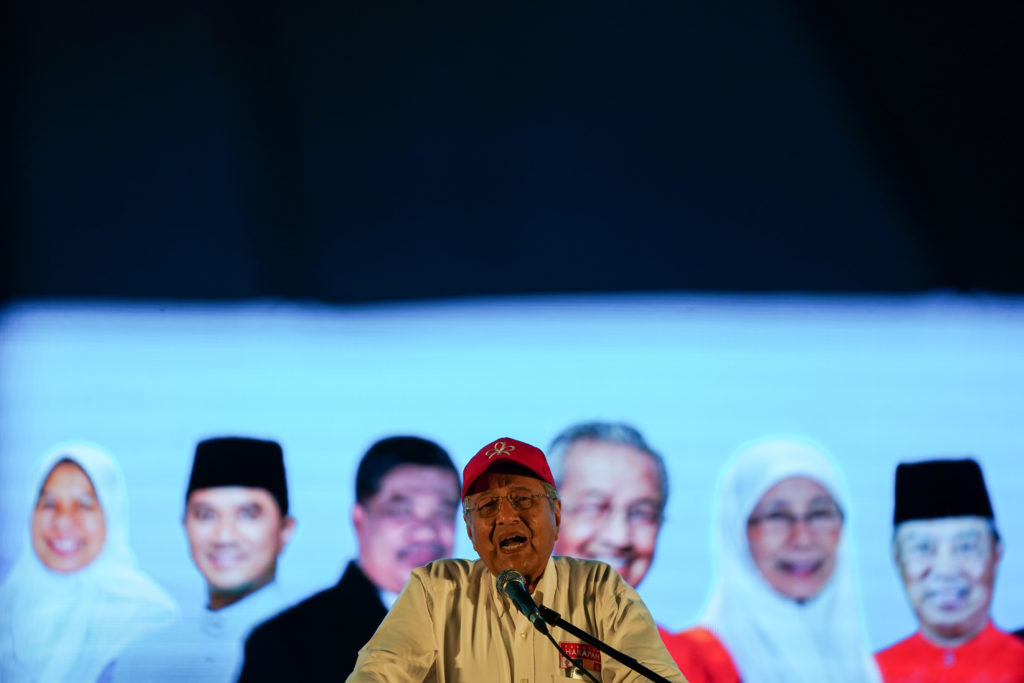

Mahathir Mohamad speaks during an election campaign rally in Kuala Lumpur, 6 May 2018. REUTERS/Athit Perawongmetha

The “wrong” two-party system

What about the argument that a large-scale rethink of the electoral system isn’t necessary? For nearly three decades since 1990, opposition parties and civil society groups have been advocating for a two-coalition system as the alternative to UMNO–BN’s one-coalition dominance. Modelled on UK’s two-party system, the idea of two-coalition competition was to have BN and a second multi-ethnic coalition competing for the middle ground and taking turns to form government.

Multi-ethnic opposition coalitions were formed thrice to take on BN in 1990, 1999 and 2013, but all of them disintegrated after their failure to dislodge BN. Thrice, the two oldest opposition parties, the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) and the secular Democratic Action Party (DAP) parted over PAS’ aggressive push for Islamisation. The fourth opposition coalition, Pakatan Harapan (PH), finally defeated BN this round. But BN seems to be biting the dust. With its ethnic Chinese and Indian support depleted, BN is virtually reduced to UMNO and its Borneo allies, which virtually all left UMNO within two months. Sarawak BN has gone independent in June 2018 as Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS), while UMNO Sabah has recently teamed up with other Sabah parties to form a new coalition, Gabungan Bersatu Sabah (GBS), just falling short of pulling out from its parental party.

While not happening at the national level, bipartism is emerging in four regions: PAS against UMNO in Kelantan and Terengganu; PH against UMNO for the rest of Peninsular Malaysia; GPS against PH in Sarawak; and PH and its regional ally Parti Warisan Sabah (Warisan) against GBS in Sabah. The four systems may be consolidated into two: PH versus UMNO-PAS in West Malaysia, and PH-Warisan versus GPS-GBS in West Malaysia. Already, UMNO and PAS are fiercely attacking PH’s policies, such as ratification of the International Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICRED), as selling out Malay-Muslim rights. Meanwhile, the Borneo parties’ push for autonomy may someday be upgraded to one for self-determination. However, further consolidation of Peninsular and Borneo opposition cannot happen because having PAS as an ally is too much an electoral liability in liberal Sabah and Sarawak.

Amid mounting challenges from both the Malay heartland and the Borneo periphery, PH’s communal and regional opposition have no incentive to offer an inclusive and cohesive platform for the whole of Malaysia. Their immediate game is to wrest legislative seats from PH’s Malay and Borneo constituencies in the next election, either to bring down PH or to force a grand coalition government. Moderation and accommodation may be on the cards when the prospect of power is within sight for UMNO, PAS, and the Borneo opposition parties—but not before they damage PH’s electoral base and strain Malaysia’s plural nation-state with their Malay-Muslim and Borneo nationalist demands. In West Malaysia particularly, a formal pact of UMNO-PAS would deliver a two-party system that resembles more Sri Lanka than Britain: if the ethnic majority is split between two blocs, while the minorities have only one viable choice, then the salience of ethnicity and religion will likely grow, with the median Malay, not the median Malaysian, playing kingmaker.

Permanent coalition’s susceptibility to implosion

The ultimate flaw of Malaysia’s party system lies in permanent coalitions a la BN, which provides no avenue for internal competition, and becomes prone to sub-competitiveness, infighting, or both. Under FPTP, constituencies are allocated to component parties on a near-permanent basis, normally based on ethnic composition of the constituencies and previous contestation history. Given only limited constituencies to contest, candidacy selection in component parties then inevitably becomes top-down, allowing party warlords to field loyalists over popular local leaders in strongholds. Combining the two, permanent coalitions often suffers in both the failure to get the strongest candidate from the strongest component party, and consequent infighting over constituencies. Structural remedies employed by BN included patronage for both voters and party elites, gerrymandering, and increase of legislative seats. While these means did not always work for BN, they must be off menu for PH if it wants real reforms.

Counter-intuitively, the absence of an unchallengeable dominant party within PH, like UMNO within BN, may only make internal peace in PH harder to sustain. Its largest component, Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) won 47 out of the 70 parliamentary constituencies contested but only 14 of its parliamentarians were appointed to the front bench. In contrast, while Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed’s Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) contested 53 constituencies and won only 13, ten of its parliamentarians are given executive positions.

While a defence may be made for Bersatu, which performed poorly for having to contest mostly in UMNO’s strongholds but delivered the necessary swing to enable PKR and DAP to win marginal seats, such over-representation in government is unlikely to be retained when PKR’s president Anwar Ibrahim succeeds Mahathir as prime minister. However, post-election cross-over may change the parties’ relative strengths, as PKR and Bersatu had so far taken in three independent parliamentarians and an ex-UMNO lawmaker respectively. If 40 more UMNO parliamentarians crosses over to Bersatu, Bersatu with 54 parliamentarians will overtake PKR (50) as the largest bloc in PH and may even challenge Anwar’s succession.

Unless open and constructive inter-ally competition is allowed, PH may soon sink into a battle royale as its component parties race to steal lawmakers from UMNO and each other. If the permanent coalition model under FPTP is retained, there might not be stability until an UMNO-like dominant party emerges to dominate the ruling coalition—but with such a party, reform is likely dead.

Electoral worker carries ballot boxes after the general election, Petaling Jaya, 9 May 2018. REUTERS/Lai Seng Sin

Making competition work

The ultimate critique against FPTP in Malaysia is not the malpractices of malapportionment and gerrymandering, but its mismatch with Malaysia’s divided society, which produces parties with strong communal or regional bases.

Under FPTP, power-sharing can only take the form of permanent coalition, but the four attempts to establish a two-coalition system since 1990 have consistently failed. A second multi-ethnic coalition can only be sustained if the winner’s victory is not too big to deplete the losers’ hope—which is unfortunately now the case for BN. Instead of promoting moderation in societies without deep divides, FPTP in Malaysia radicalises the desperate opposition, which in turn places strain on the centrist ruling coalition.

Further, permanent coalitions under FPTP have no room for internal competition and bottom-up candidacy selection, which in turn breeds infighting and implosion. Ironically, the stronger the landslide, the likelier the ruling coalition may implode. BN’s ouster in 2018 could be traced back to its 2004 landslide when its 91% parliamentary majority induced arrogance and infightings that ushered in a political tsunami four years later.

Multiparty democracy is about choosing an opposition as much as choosing a government. What threatens Malaysia’s democracy is not communal parties—which the ethnically, religiously and linguistically diverse society naturally produces—but the wrong incentives that drive government and opposition parties into malign competition. Malaysians must stop thinking that what fits England would fit Malaysia. Instead of a Westminster-style majoritarian democracy, a “consensus democracy” where all groups freely compete, then share power through endless possibilities of post-election coalition governments, may be more compatible.

As radical as it sounds, moving away from FPTP to some form of proportional representation electoral system may be the most realistic solution to ensure political stability in Malaysia. But that necessitates frank conversations and rigorous debates across the communal and partisan divides. If Malaysia is to explore other alternatives, be it Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP), Mixed-Member Majoritarian (MMM) or Party-List Proportional Representation (List-PR) as in neighbouring Indonesia, civil society groups and political parties must work together to start a national conversation and forge consensus.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss