In the days following his inauguration on 20 October, President Prabowo Subianto moved quickly to appoint a total of 136 coordinating ministers, ministers and their deputies, agency chiefs and their deputies, and special envoy/advisor posts. With 48 of these being ministerial or ministerial-equivalent positions, no New Order or post-reformasi cabinet has had more members than what Prabowo has dubbed his “Red and White” cabinet.

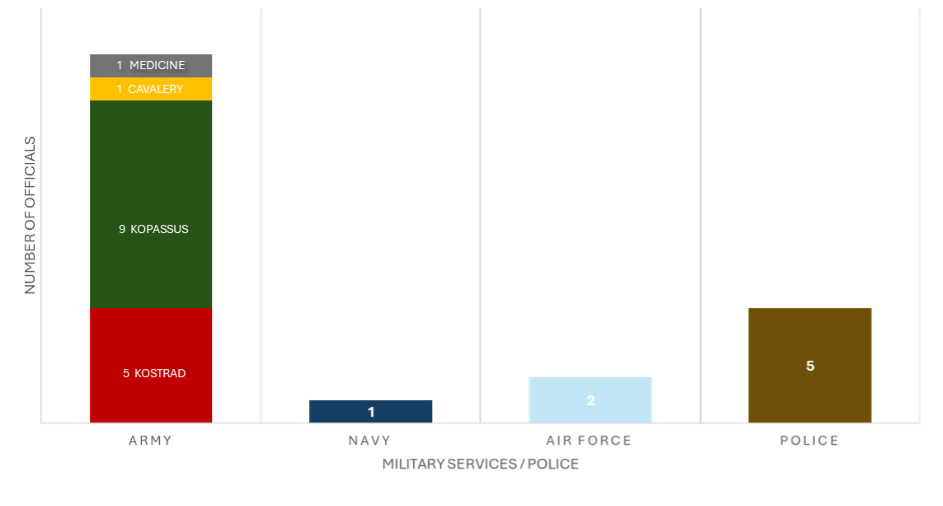

What also stands out is that the cabinet also includes the largest-ever number of individuals with military and police backgrounds. These retirees, called purnawirawan in Bahasa Indonesia, now fill a number of strategic positions in Prabowo’s cabinet. A dataset of cabinet appointments we have compiled turns up at least 23 purnawirawan and one active military officer — many of them with army backgrounds (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Red and White Cabinet Members with Military / Police Background

Dataset compiled by authors from various news sources

In particular Prabowo has appointed die-hard loyalists with backgrounds in the army’s special forces unit, Kopassus (Komando Pasukan Khusus). A number of key appointments went to ex-Kopassus troops with close links to the new president. Prabowo has established a new development-related agency called Development Oversight and Special Investigation (Badan Pengendalian Pembangunan dan Investigasi Khusus or BPPIK). As its name suggests, this ministerial-level agency aims to monitor and evaluate the implementation of development programs and to ensure transparency as well accountability for use of state budget fund. Prabowo appointed Aries Marsudiyanto, a former Kopassus officer and the leader of Prabowo’s presidential campaign team in West Java, to head BBPIK.

The new foreign minister Sugiono has meanwhile long been known as a protege of Prabowo. Though he managed to join Kopassus, Sugiono’s military career was relatively short as he resigned with the rank of first lieutenant. Minister of Defence Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin is another case in point: he has been a close friend of Prabowo since both of them served as Kopassus officers. Sjafrie was once the military adjutant of Suharto and held a prestigious post as the commander of Jakarta’s military area command (Kodam Jaya) during the tumultuous times in 1997–1998. In 2010–2014, Sjafrie was deputy minister of defence, and during Prabowo’s tenure as defence minister (2019–2024) he served on Prabowo’s ministerial special staff with responsibility for defence management. The newly appointed head of the National Intelligence Agency (Badan Intelijen Negara or BIN) Muhammad Herindra is also an ex-Kopassus officer, having an extensive professional experience in the intelligence services and as a former deputy minister of defence.

This is not the first time that ex-Kopassus personnel have held strategic posts in the executive: during the presidencies of Joko Widodo and Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, ex-Kopassus officers were appointed to various ministerial positions. Nevertheless, we would argue that the fact that the bulk of ex-army appointments in Prabowo’s cabinet — 9 out of 16 — have Kopassus backgrounds, many with personal links to the president, signifies Prabowo’s prioritisation of political stability and power consolidation.

Agents of developmentalism

How will Prabowo make use of this corps of ex-military figures in his government? One possible way to answer the question is to look at how the Indonesian military perceives its role beyond defence affairs. Despite the mandate to “return to the barracks” following as part of the post-1998 democratising reforms, in reality we still see the creeping expansion of a military role beyond defence affairs.

Former president Joko Widodo infamously signed a dozen memoranda of understanding with TNI to boost the progress of his various economic and infrastructure projects, and it appears likely that there will be a similar convergence of Prabowo’s pursuit of his ambitious projects and the military’s interests in expanding its role as an agent of developmentalism.

During his 2024 presidential campaign, Prabowo outlined his intention to provide free lunch for Indonesian children in what experts said was an ambitious program that could consume much of the state budget. Furthermore, the free lunch programme — now branded as “free nutritious food for children” — is not the only mega project in Prabowo’s list of priorities, which also include “food resilience (ketahanan pangan)”, achieved through food self-sufficiency (swasembada pangan).

The National Nutrition Agency (Badan Gizi Nasional) has highlighted the need for the involvement of various parts of the government, including the military, to implement the free meal and food resilience programmes. The government will reportedly mobilise the military’s extensive territorial command structure to organise and distribute the food packages to schools: the military’s role will not stop at the implementation level, but also in policy decisions through the inclusion of retired military officers in the structural organisation of the National Nutrition Agency. Those purnawirawan are said to have experience and leadership to undertake such difficult tasks, implying that military operations and health services are two sides of the same coin.

Kekaryaan comeback

The inclusion of so many purnawirawan in Prabowo’s cabinet and the key role military-linked figures are set to play in delivering his key programs speaks to the persistence of the kekaryaan (service) concept. An element of the broader doctrine of military dwifungsi (dual function)which during the New Order recognised the Indonesian military as both a defence tool and a crucial part of the nation’s socio-economic development, kekaryaan underpinned the practice of secondment of serving military officers to civilian institutions.

The reality that kekaryaan has never completely faded from the military’s thinking dovetails with the more practical political ambitions that are driving officers’ engagement with politics. As our previous studies on the political activities retired military officers in Indonesia have shown, protection of personal interests and attempt to extend their skills are key drivers for them to join politics.

Jokowi broke the ‘Reformasi coalition’

The outgoing president transformed the relationship between government and civil society in his decade in power

But while the incorporation of retired military officers can be a quick win strategy for Prabowo, both in terms of governance results and political stability, overreliance on the military is also a hazard. The co-optation of the military into Prabowo’s developmentalist agenda could weaken civilian capability in the long term and increase the politicisation of the military which may jeopardise the defence capability of the armed forces.

As former high ranking officers’ influence over military or police institutions rarely wane following their retirement, there is a likelihood of further mobilisation of TNI (as well as police) structures and resources to support the government’s ambitious development programs, which are beyond the security institutions’ expertise and operational scope. Thus, this situation might distract the core focus of the military and police and put a question on their readiness to do their “real” jobs.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss