“Knock, knock, knock! Let’s go out to vote!” says a promotional music video reminding Thais to vote in the general election on 24 March 2019. And people really should vote, say the three female singers, because democracy has been “lost” for a while.

At the start of the song, we are introduced to the singers: first time voters who would have been just 13-15 years old when General Prayut executed his coup in 2014, putting a “freeze” on Thai democracy. “Where have you disappeared?” they ask, as if speaking to democracy itself. “Always coming and going, or did someone steal you?” (หายไปไหนมา ประชาธิปไตย แวบมาวูบไปหรือใครช่วงชิง). The song was produced by media company Katikala, who wanted to encourage young people to engage with the upcoming election.

Thailand has a long history of using music to promote elections. But whereas the songs nowadays are set to well-produced videos and circulated online, in the past they were made the old-fashioned way: on vinyl.

Although Thailand had a booming record industry in the 1960s and 1970s, the election records would have held little interest for the commercial market. Instead, they were made by government agencies and distributed to radio stations around the country to raise awareness and encourage people to vote. Since most households in Thailand had wireless radios at that time, the election songs likely had a much wider audience than 2019’s Knock, Knock, Knock, which struggled to compete for attention amidst the online throng (amassing only some 80, 000 views by the eve of election day).

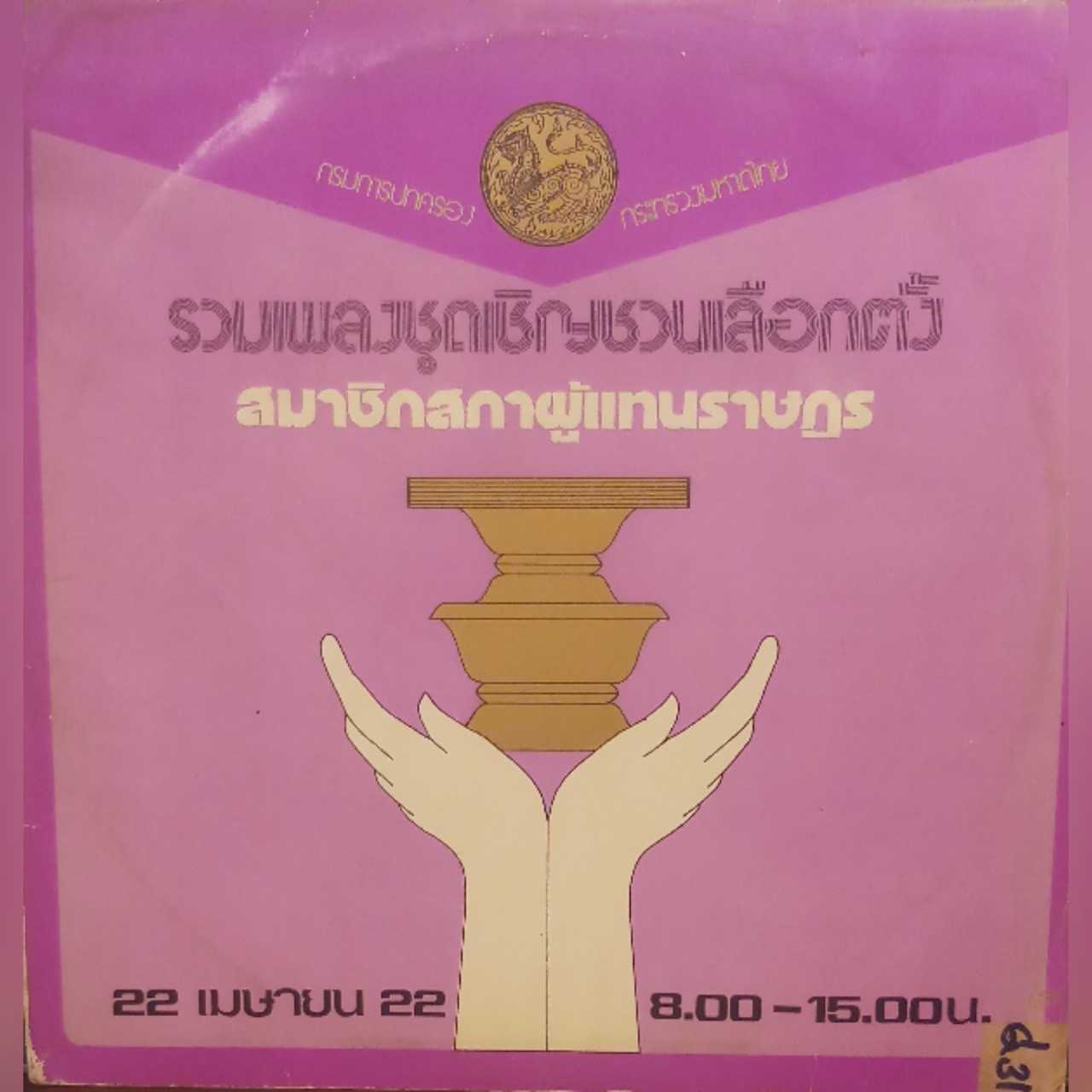

I own two such vinyl records, promoting the elections of April 1976 and April 1979. They were produced by the Government Public Relations Department and the Department of Provincial Administration respectively. I was also able to find another on YouTube, publicising the elections of January 1975. The albums feature a variety of Thai musical genres with vocals in different regional dialects, allowing DJs to choose the best option for their audience. As historical documents, they give us insight into the elections and politics of one of Thailand’s most turbulent decades.

The 1976 election record

In January 1975, Thailand was enjoying a period of relative democratic openness. Student-led protests in 14 October 1973 had rid the country of the “three tyrants”: Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn, his son Colonel Narong, and Narong’s father-in-law General Praphas Charusathien.

Now freed from a despised dictatorship, the songs express an optimism and desire for more worthy representatives. “Choose good people, who are trustworthy. It’s a good opportunity to look for leaders who are capable,” voters are told in one song (เลือกคนดีที่ไว้ใจ โอกาสดีที่จะหาผู้แทนที่เก่ง). “We were able to get democracy, we were able to get a constitution. So don’t squander your rights that people died fighting for,” says another, reminding listeners of the debt they owed to those killed by security forces on 14 October 1973 (เพราะเราได้มาประชาธิปไตย เพราะได้รัฐธรรมนูญมา แม้จะเสียชีวิตไป อย่ามัวใช้สิทธิในทางตัน เพลง: เห่ เลือกตั้ง).

The Democrat Party, led by Sen Pramoj, won the largest number of seats in the January polls that year but was unable to form a viable coalition. By March, his brother and political rival Kukrit managed to piece together a coalition of centrist to right-wing parties, led by his Social Action Party. But the coalition was messy and faced strong opposition from the Democrats and a number of left-wing parties, who had fared rather well in the election. After a chaotic ten months, Kukrit’s 16-party coalition broke down and he dissolved parliament to hold a fresh election.

The record promoting the vote on April 1976 has quite a different tone from the January 1975 album. The sense of optimism and pride in democracy is replaced by a fear of communism and desire for stability.

Several songs mention the chaos of the previous parliament (for example, ที่แล้วมาสภาผู้แทนต้องยุบ มุ่งทำลายกันแหลกลาญ) and urge people to focus on electing a party rather than individual representatives, in the hope of forming a more stable government (เลือกพรรคกันดีกว่า อย่าเห็นแก่หน้าโดยเลือกบุคคล). The songs implore voters to reach a stronger public consensus (เพื่อมติของมหาชน) to bring harmony to the nation (สามัคคีกันเถิดไทยเอย).

Much of the record carries a stringently anti-communist message, with communists dismissed as “villains, who have bad intentions and cause divisions” (คอมมิวนิสต์คิดชั่ว ตัวร้าย ทำให้แตกแยก). The refrain “don’t choose the communists” (อย่าไปเลือกคอมมิวนิสต์) echoes throughout the recording, with listeners told that communism isn’t suitable for Thailand (นิยมคอมมิวนิสต์อย่าไปเลือกมัน ไม่เหมาะกับประเทศไทย). Instead, voters should choose a party whose policies protect the nation, religion and monarchy (เลือกพรรคที่มีนโยบายบำรุงชาติ ศาสน์ กษัตริย์). By contrast, it is claimed the communists seek to damage Thailand’s ‘three pillars’ (ชาติ ศาสน์ กษัตริย์ จะถูกทำลาย).

The record reflects the rising anti-communist hysteria of the time and the songs when played on the radio would have fuelled the fire. The newly founded Thai Nation Party—now Chartthaipattana Party—contested the election under the slogan “the Right should kill the Left” (ขวาพิฆาตซ้าย) and Boonsanong Punyodyana, a leader of the Socialist Party of Thailand was indeed murdered shortly before the election. His party had won 15 seats in the poll the previous year.

On election day on 4 April 1976, Seni Pramoj’s Democrat Party again won the most votes and was this time able to form a coalition. But the country’s politics remained volatile and by October things reached a boiling point when right-wing mobs and state security forces massacred left-leaning students at Thammasat University. Seni was overthrown by a right-wing military coup shortly afterwards and democracy “disappeared” again.

After three years of military rule, Thailand went to the polls again in April 1979. Kukrit Pramoj’s Social Action Party won the most votes and could easily have formed a coalition with other royalist-conservative parties, but instead capitulated to the military by nominating General Kriangsak Chomanan to stay on as prime minister. Kriangsak retired a year later and Thailand’s entered its 8-year period of guided democracy—or Premocracy—under General Prem Tinsulanonda. Elections were held in 1983 and 1986 but the parliament was subordinated to Prem and the palace.

The election record for April 1979 demonstrates the beginning of this new hollow politics quite well. There is nothing like the optimism of 1975, or even the contention of 1976. The lyrics are stripped of all real meaning and seem to reduce the election to a mere administrative task, with much obsessing over making sure that voters’ names on the electoral register matched those on their house registration document and national ID card (ตรวจบัญชีว่ามีชื่อเลือกตั้ง, บัตรประชาชน ชื่อในทะเบียนบ้านตรงกับชื่อในบัญชีผู้มีสิทธิเลือกตั้ง).

There is also no mention of communists, indicating a change in policy under Kriangsak and Prem, who were concerned that the harsh measures of the 1970s were merely generating public sympathy for the communists and boosting their ranks. Both leaders worked hard on conciliatory measures instead, which included an amnesty to former communist cadres. By the mid-to-late 1980s, the Communist Party of Thailand was in serious decline, as was left-wing politics more generally.

The 1979 election record

With the proliferation of music cassettes and compact discs throughout the 1980s and 1990s, vinyl was also in decline. It’s not clear when the last vinyl record promoting a Thai election was produced but had they continued until today, lyrics may have mentioned further military coups in 1991, 2006 and 2014. Some songs might also have covered the killing of unarmed protesters in 1992 and the chaos and violence that has plagued Thailand since the 2006 coup, including the murderous military crackdown on red-shirt protestors in 2010.

The election song Thailand desperately needs is one that looks back on its vicious circle of crises, coups, protests and military massacres as a thing of the distant past. A rousing anthem about unity in diversity, with a chorus celebrating a mature electoral process, and verses extolling the smooth and peaceful transfer of power at the ballot box—with all sides accepting the results.

Sadly, the 2019 election seems unlikely to herald such an era. The electoral process has lacked legitimacy since the beginning and the aftermath seems destined to be contentious. All indications are that the vote will lead to a parliamentary crisis, which could give way to street protests once again. And so the vicious circle of Thai politics keeps on turning, like a bad vinyl record playing on repeat.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss