The clamour

The early years of Prime Minister Mahathir’s first incarnation in 1981 saw a distinct character to Islamic governance. There was greater centralisation of Islamic authority, more acute standardisation of religious expressions, corporatisation of Islamic monetary resources, and the enclosing of Muslim subjects within syariah legalism. The powers and legitimacy of this bureaucracy drew from formal statutes, organisational systems, rational management of human and capital resources, and a differentiation of functions; all very typical of Weberian bureaucracy but for one additional and crucial dimension. This dimension—sacrosanctity and inviolability derived from revelatory and founding texts of the Quran, the prophetic traditions of hadith and sunna, and ancient and contemporary fiqh texts—imprints the exceptional authority of Malaysia’s Islamic bureaucracy, or what can be called the Divine Bureaucracy.

After the May 2018 electoral turnaround, the terrain of Islamic reform has remained the most slippery of transformative spheres the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government confronts—not least due to the resilience of the Divine Bureaucracy. The early aftermath of PH’s election victory saw several groups and individuals coming out boldly to urge a reexamination of some of the excesses of Islamic bureaucratic authority under the previous Barisan Nasional (BN) government. However, this gradually faded to a more muted, if not resigned acceptance of the status quo.

Very soon after the 2018 general election, the G25, a group of Muslim former top civil service officers, judges, ambassadors and public scholars, called on the Council of Rulers to review the function of JAKIM (Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia, Islamic Advancement Department of Malaysia). JAKIM has been the dominant face of bureaucratic Islam, being Malaysia’s foremost federal-level institution for the development and management of Islam. In a way, it epitomised the Divine Bureaucracy.

One member of G25 pressed for JAKIM’s immediate dissolution since it was purportedly unconstitutional, being set up under Federal authority rather under the purview of State governments as Islamic governance is meant to be. In his laundry list of possible reforms in the area of Islamic affairs, Zan Azlee, a columnist for the online news portal Malaysiakini, also targeted JAKIM, questioning its stance on matters such as the LGBT community and Muslims’ exclusive use of the word “Allah”. Citing Mahathir, he argued that JAKIM should ensure that Islam is not portrayed as a cruel and inconsiderate religion.

In June 2018, Prime Minister Mahathir announced that JAKIM’s roles and functions would be reviewed and assessed. The PM’s proposal was not well-received by some quarters, particularly by a Malay-rights group called Pemantau Malaysia Baru, which threatened to hold a rally if JAKIM’s role were reviewed. The group also protested against the alleged withholding of mosque-upgrading funds and salaries of teachers of Quranic classes (KAFA).

Nevertheless, the Mahathir government went ahead and established a High-Level Committee on Federal Islamic Affairs Institutions (Jawatankuasa Tertinggi Institusi Hal Ehwal Islam Peringkat Persekutuan) in late July 2018, with the approval of the Council of Rulers. The Committee was headed by Ahmad Sarji Abdul Hamid, former Chief Secretary to the Federal Government, while Afifi Al-Akiti, a fellow at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, was named his deputy. To date the Committee has not released the results of their study.

How far, then, are efforts to clear JAKIM of its increasingly partisan and religiously and ethnically divisive role in government to likely to progress under the new PH government? Where Islamic administration and authority are concerned, there seem to be two opposing trends under PH. On the one hand, the newly-elected government appears to be responding positively to criticisms of the excesses of previous Islamic governance. On the other hand, the old agenda and orientations of the Islamic Bureaucracy seem too resilient to undo. Strategies of both censure and compassion have been used to address the issue of Islamisation, but the authority of the Divine Bureaucracy has remained solidly intact.

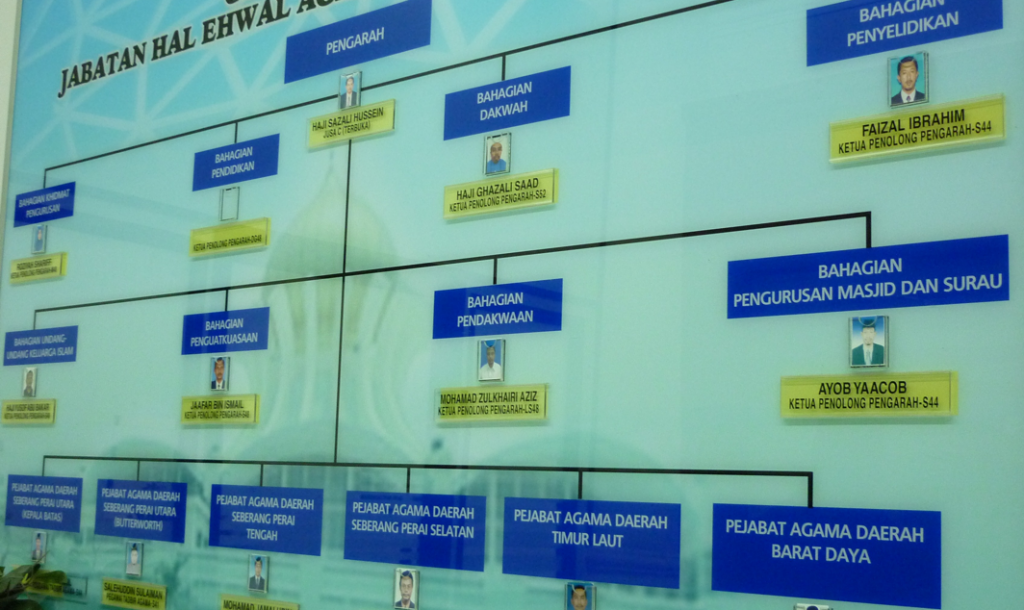

The Divine Bureaucracy as Mediator of Applications (photo: author)

Censure

One of the new government’s first targets for closure was Institut Kajian Strategik Islam Malaysia (IKSIM, Institute of Islamic Strategic Research Malaysia). This outfit was set up in 2012, ostensibly to redress the LGBT issue, which was portrayed as threatening the faith and creed (akidah) of Muslims.

Formed with the approval of JAKIM and State Islamic Religious Councils, IKSIM was set up as a company, rather than a government agency, and was headed by the then de facto Minister of Islamic Affairs, Jamil Khir Baharom. IKSIM was also funded by zakat funds from the Federal Territories Religious Council (MAIWP), to the tune of RM10 million (A$3.4 million) in 2018. Prominent academic and legal expert Shad Faruqi wrote about a booklet IKSIM had produced declaring that secularism, liberalism and cultural diversity could undermine the Islamic agenda, while asserting that the country should not be obliged to protect other religions. The group subsequently lodged a police report against Faruqi in reponse.

Early in 2018, one of IKSIM’s research fellows even urged that a fatwa be issued to make it haram for Muslims to vote for the Democratic Action Party in the 2018 general election, allegedly because the party was anti-Islam. IKSIM had also labelled Mujahid Rawa and other Muslim opposition politicians as supporters of liberalism, pluralism and LGBTs.

The organisation is alleged to have mismanaged its funds, of which some RM7 million from the government were unaccounted for. When IKSIM’s funding was withdrawn after the PH government came to power, it attacked PH as having been voted in by non-Muslims and as upholders of a liberal-secular agenda that threatened the supremacy of Islam in the nation. It is difficult not to associate the formation of IKSIM with the political agenda of UMNO, which may have used this anti-liberalism and anti-secularism narrative to dissuade Muslims from voting for the then-opposition.

Compassion

Beyond such censure, though, the PH government has also portrayed compassion as the role of religion. In a keynote speech given in early 2019, Minister Mujahid Rawa expounded upon the concepts of rahmatan lil ‘alamin and maqasid syariah as two of three pillars under the PH Government’s new thrust for Islamic development in the country; the third pillar is the manhaj Malizi (Malaysian Model) of Islamisation. The concept rahmatan lil ‘alamin denotes the universal good: that God’s blessing is for the whole universe, regardless of ethnicity and culture, with love, unity and tolerance as its key underpinnings. Maqasid syariah stresses that every decision and action must consider the interests of a multiracial society, to avoid hate and religious and racial misunderstanding. The manhaj Malizi requires that the approach to all of this be appropriately local, taking into account Malaysia’s unique ethnic, religious and cultural diversity. Diversity and pluralism must be suited to Malaysia’s own manhaj (method) of addressing Islam and other religious beliefs, particular and unique to the country’s setting. In short, the new government aspires to instil a more compassionate form of Islam.

Aside from avoiding hatred and enmity among religions and adopting an appropriate Malaysian model of ethnic pluralism, the terms, blessings (rahmah), peace (aman), harmony (harmoni), congeniality (mesra) and respect (hormat) are to be emphasised, as well. This approach derives from the Quran, surah al-Anbiya, verse 107, which states, “We have sent you forth as nothing but mercy to people of the whole world” (Kami tidak mengutuskan engkau, wahai Muhammad, melainkan sebagai rahmat bagi seluruh manusia), and presents Islam as a religion of blessings or love (rahmat) for all, hence allowing the possibility of interfaith dialogue and understanding.

Criticisms

Detractors on social media have not taken too kindly to this compassionate approach to cultivating harmony, insisting that it would put Islam on the same level as other religions. Others claimed that this framework represented the usual platitudes of new Malaysian governments, comparable to Penerapan Nilai-Nilai Islam under Mahathir, Islam Hadhari under Abdullah Badawi and wasatiyyah under Najib. Minister Mujahid himself was accused of being a liberal in implementing the rahmatan lil alamin. According to one Muslim scholar, even though the notion of universal tolerance and acceptance derives from a Quranic verse, it must still be accepted with caution and does mean being “apologetic” to the extent of compromising on Islamic principles against LGBT for example.

As expected, UMNO and PAS also criticised this approach. UMNO claimed that it would be abused for vote-baiting and to promote the freedom of “deviant” groups such as Syiah, Qadiani, and LGBTs, while PAS maintained that the PH Government appeared to be trying to protect the rights of non-Muslims over Muslims. It also reminded the minister to be careful to ensure the Muslim faith was still strongly based on akidah, rather than anything else. This resort to akidah replays the strategy of JAKIM under the old administration, drawing a line between compliant Muslims and those outside the ambit of the Divine Bureaucracy. To be sure, the appropriateness of the present government’s usage of rahmatan lil alamin has spurred some intellectual debates, although for now it is still tentatively accepted by sceptical Islamic factions.

The author interviewing PAS woman campaigner during Malaysia’s 14th general election (photo: author)

Caving in

One of Mujahid’s more “radical” ideas, in his early days, as reported by a newspaper which had an exclusive interview with him, was to stop religious enforcers from carrying out midnight raids on couples found in close proximity (khalwat). He distinguished between committing wrongs in private versus in public spaces, noting that what went on in private was not the concern of enforcement officers. PM Mahathir supported this view, saying, “If you have to climb inside a person’s house and all that (to find wrongdoings), that is not Islam”. All this did not go down well with the traditional bureaucracy, especially the mufti from various states. Those from the states of Pahang, Perak and Negeri Sembilan, in particular, flexed their muscles and asserted that it was within state-assigned powers to prevent vice wherever it happened. A day later, the minister distanced himself from his own earlier statement and claimed that the news report had misrepresented his views. Mujahid sought an apology from the newspaper, which then declared that it regretted having misrepresented his words.

Following an International Women’s Day rally in the capital city on 8 March 2018, Mujahid again came under the spotlight when he chastised its organisers for allegedly promoting LGBT rights, which he insisted was an abuse of democracy. This invited counter-reactions from civil society, including from the Centre for Independent Journalism, which said that his misogynistic insinuations were uncalled for and tantamount to the government’s trivialising women’s issues.

In November 2018, the new government also backed down from its intention to ratify the United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). This retreat was after Malay and Muslim parties and NGOs held a rally to protest against the treaty, claiming that it would abolish the rights of Malays and the privileges of Malay rulers, and contravene religious strictures of Islam.

The forgotten voters: the Orang Asli in the Malaysia Baru

"Pengundi yang dilupakan: Orang Asli dan Malaysia Baru"

In terms of funding, the federal government raised its budget allocation for Islamic development by RM13 million in 2019 from the previous year. It gave an additional RM50 million to religious schools not under the administration of state or federal governments, RM25 million for registered pondok schools, and RM150 million for mosque and surau repairs.

Minister Muhajid’s caving in to pressure from the Divine Bureaucracy shows how the Islamic bureaucracy and its non-governmental allies can draw power beyond that of elected authorities. The bureaucracy is a “permanent apparatus” for the use of different rulers. At least for the first year after the installation of the new Government, the Divine Bureaucracy prevailed in most questions related to Islam, as this exceptional bureaucracy is not answerable to any constituency or vote bank and continued to operate as usual, despite the change in political leadership. The Divine Bureaucracy’s roles in the overarching project and resurgence of Islamisation span at least three domains of Islamic bureaucracies—at the negeri (state), federal and corporate levels, attesting to the vast and interlocking extent of its governance, authority and control over the social life of Muslims.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss