This week at New Mandala, PoP is excited to present a fresh perspective on Indonesian artistic and heritage practice. Greg Doyle takes us through a dazzling catalogue of contemporary art in Indonesia that challenges the conservative notion that such art has to incorporate ethno-cultural ‘traditions’. This resistance to tradition is grounded in both past politics and present pragmatism.

Recently, the curator at a major Australian gallery told me that it was a matter of policy that new Indonesian art demonstrate ties to the archipelago’s traditional cultures. At this gallery, the value of Indonesian art is found in its connection to belief systems and material culture from prior to Indonesia’s independence. Consequently, the gallery’s collection is quite anthropological and weighted towards textiles. While this might be attributable to the institution’s conservatism, it also demonstrates a larger tendency to essentialise Indonesia. While Indonesia is undeniably culturally distinct, its cultural products are not necessarily rooted in specific ethno-cultural traditions. Building on a long history of modernist engagement with international art worlds, many contemporary Indonesian artists work with ideas that would challenge Indonesia’s Sukarnoist and Suhartoist cultural engineers as they appropriated the pre-modern to construct a new Indonesian identity.

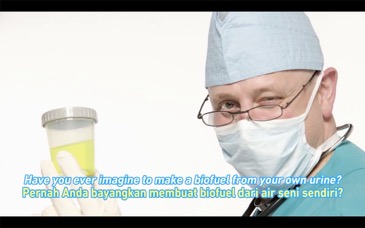

Togar (Julian Abraham), diabethanol video still. Source: 2018 Sydney Biennale

Take diabethanol, Togar’s recent contribution to the 2018 Sydney Biennale. This is a strongly researched, and wryly humorous, piece linking a global health crisis to the purported global energy crisis. Indonesia is potentially affected by both crises. However, apart from Indonesian subtitles for the English language voiceover, there is nothing in the aesthetics of the piece to link it to Indonesia. Highly manufactured, and with near-flawless production values, this work could have been the creation of an artist from anywhere in the global contemporary art world. It is only in the curatorial notes that a link is made to an ambiguous Indonesian aphorism, mengambil kesempatan dalam kesempitan (take an opportunity from a misfortune). Other than that, one is very hard pressed to find anything specifically Indonesian in the installation.

Like many contemporary artists from Indonesia, Togar draws inspiration from a globalised culture. In a 2017 interview in Yogyakarta, he described being influenced by electronic music, science and technology. These interests are evident in his work, which he proudly notes could be produced in any country. Togar is also clear that the values of the Indonesian art world are fluid and contingent. While members of some collectives are united behind similar ideological and aesthetic perspectives, the art world itself is pluralistic. This pluralism was emphasised, and clearly valued, in interviews I conducted with numerous artists and curators in Yogyakarta in 2017.

Several other interviewees in Yogyakarta noted that Indonesian art is a little like Indonesian Islam, in that while everyone values the larger ummat (community), there are many divergent aliran (streams) reflecting different values and respecting different kyai or influential leaders. As has long been the case in Indonesia, one of the biggest differences between the various artistic aliran is how they engage with the question of Indonesia. This great debate, as Claire Holt described it, has been playing out in one form or another since before independence. At its centre is the friction between cosmopolitanism and various interpretations of keindonesianan, or Indonesianness. While Sukarno and Suharto both wanted an art that expressly (Sukarno) or benignly (Suharto) supported their attempts at cultural construction of a national imaginary, independent currents in the art world have always looked outwards for inspiration – first at modernity, then briefly and unproductively at post-modernity, and now at contemporaneity.

Ever since Indonesian contemporary art emerged into the international scene in the 1990s it has been expected to say something about Indonesia. In the main, private and institutional collectors have both wanted either reference to traditional aesthetics or rebellious political content and social commentary. However, Indonesia’s contemporary artists have become too sensitive, too subtle and too sophisticated to be comfortable meeting these demands.

Some might suggest they have also become too pragmatic as they chase global art world trends. Younger artists are taking their cues from global journals like e-flux and frieze and from the art they see as they travel the globe and explore the Internet. One senior artist derided artists working with traditional motifs as merely producing oleh-oleh or tourist tat.

FX Harsono, The Raining Bed (2013), Source: Arndt Fine Art. A version of this artwork was also shown in the 2016 Sydney Biennale

Certainly, there remain artists leveraging the specifics of Indonesian society and politics. FX Harsono (see image above) and Dadang Christanto continue to examine historically-rooted questions of violence and identity. Heri Dono looks at current affairs through the filter of folk traditions. There also remain artists like Nasirun who draw on premodern traditions of mysticism and spirituality.

As important and relevant as these artists are, however, they increasingly appear a little detached from the zeitgeist of zaman now (the present period of globalised creative and aesthetic nowness), as I have heard art’s current moment laughingly described in Yogyakarta.

Hahan, Young Speculative Wanderers 2014-2015, detail from larger installation at 2018 NGV Triennial. Source: National Gallery of Victoria

Several trends characterise this moment in Yogyakarta. First, consistent with trends in the larger contemporary art world, many artists have turned away from traditional media. Painting, as I saw one internationally-famous artist post on Instagram last year, is (yet again) dead. Multi-medium installations are the order of the day. The death of painting has been a challenge for many artists associated with Yogyakarta’s longstanding graphic arts culture. Even those artists relying on strong drawing and painting skills, like Hahan, are dressing up their images as installations. This strategy seems to be paying off for Hahan, who is one of the hottest Indonesian artists in Australia at present.

One of the problems with the move to installations and art at scale is that it has dramatically altered the market for art. Art is now designed to fill a room rather than hang on a wall. As such its target market is institutions rather than individual collectors. The commissioned works at Art Jog this year and last give an indication of the way art is going. The massive Floating Eyes work by Wedhar Riyadi and Mulyana’s Sea Remembers are explicitly designed for museums. The goal of most contemporary artists is now to obtain international residencies and a slot in a major biennale. The experience of many artists is that this is a profitable career strategy especially if one develops a merchandising business on the side. Hahan, for example, sells his merchandise through the National Gallery of Victoria shop and Eko Nugroho retails his online.

The shift to an artistic economy based on residencies and institutional commissions comes after more than a decade of hard economic times for much of the Indonesian art world. After the frenzied speculation of the early 2000’s many artists resent the transparent commodification of their work. While some, particularly those from Sumatra, seem to value market success as a mark of achievement, others express a distaste for commercialism. Believing in art for art’s sake, and possessing a vague hostility towards capitalism, these artists see institutional and state grants as a more ethical way of funding the production of art. In the absence of much state or institutional support from within Indonesia, their focus of such artists is inevitably on opportunities within the international art world. There seems to be no shortage of such opportunities. Eko Nugroho for example, had 15 international residencies between 2004 and 2012. Of course, he then collaborated with Louis Vuitton in 2013, leading one to question where he sits on the issue of commodification.

Eko Nugroho, Lot Lost (2013-2015). Source: AGNSW

Moving forward, I think that anyone looking for keindonesianan (Indonesianness) in contemporary works from Indonesia will be increasingly disappointed. Indonesian art is firmly embedded in the global art world and it is rapidly adopting the aesthetic language of that world. In this field at least, Indonesians are asking to be judged by global standards against which they increasingly hold their own. Hopefully Australian institutions will begin to take a much more expansive view of what Indonesian art has to offer. Our collections will be richer for it.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss