The Cambodian government is increasingly critical of the international human rights community, Rebecca Gidley writes.

The Cambodian government is sick of being seen as special. Not by its electorate, but by the international human rights community.

The memorandum of understanding between the government and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) expired a year ago, and in the last month the government has stepped up its rhetoric against the office. Foreign Minister Prak Sokhon has accused the OHCHR of “prejudice” and a government spokesperson called the continued operation of OHCHR “illegal”. The government is refusing to agree to renew the memorandum of understanding unless it includes new references to non-interference by the UN in domestic affairs.

This most recent stoush was sparked by comments made about opposition leader Sam Rainsy. Recently, during his third stint of self-imposed exile to avoid a jail sentence in Cambodia, Rainsy was banned from returning to the country – which he was quick to point out meant he was no longer in “self-imposed exile”. The opposition party has argued that this action is unconstitutional, and the OHCHR requested an explanation from the government which prompted the government’s accusations of prejudice.

Other UN human rights staff in Cambodia have come under fire in the recent past. One local OHCHR staff member was threatened with arrest in a high-profile case related to the mistress of deputy opposition leader Kem Sokha. Multiple UN Secretary General’s Special Representatives for Human Rights have resigned in the face of government officials refusing to meet with them. Yash Ghai of Kenya, who resigned the post in 2008, said Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen had called him “deranged” and “lazy” and that a government spokesperson had called him “uncivilized and lacking Aryan culture”.

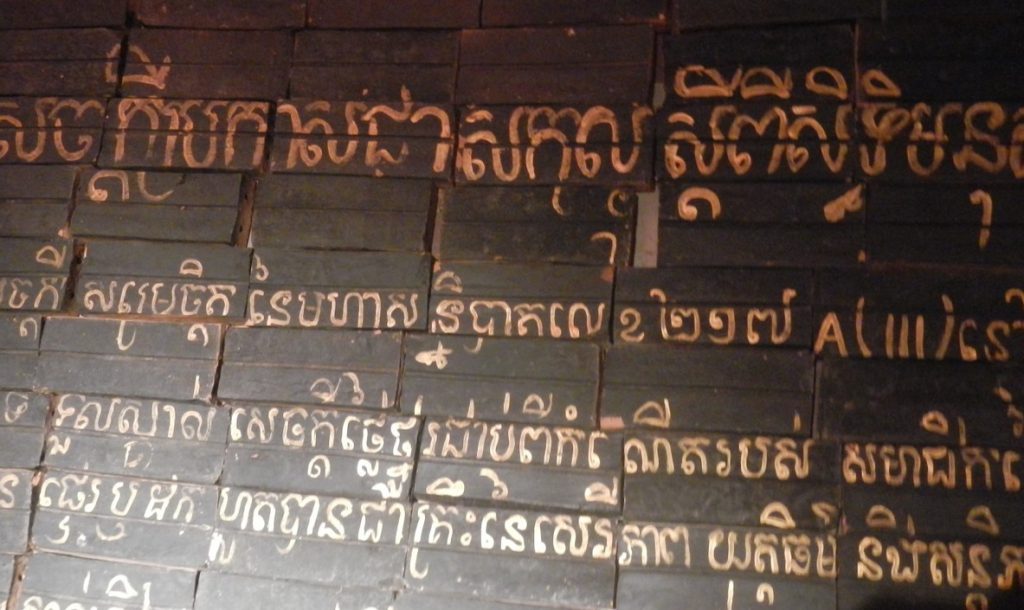

Cambodia is one of only 14 countries to currently have a special mandate for a UN human rights envoy. This mandate has been in place since 1993, when the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia organised Cambodia’s first election in decades.

The UN’s Cambodia mission is regarded as a success for the organisation and so they are keen to preserve the legacy of this “jewel in the crown” of UN peacekeeping. International donors also make up 30 to 40 per cent of Cambodia’s national budget, and hence want to remain an active voice in Cambodian affairs. Locally, the opposition party is also keen to capitalise on this ongoing international concern and encourage international intervention by arguing that the states which created the UN mission by signing the 1991 Paris Peace Agreement “have the obligation to ensure the full implementation of the agreement.”

The Cambodian government has also played into this situation in a quest for greater international legitimacy, including from the UN. In 2005, the government sought a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council and cited its past cooperation with the UN to justify its suitability. Cambodia was also the first Southeast Asian nation to sign the Rome Statute on the International Criminal Court and government leaders often praise the work that Cambodian landmine clearance teams do in other UN missions.

However, if the government has taken to lashing out at international criticism far more frequently, it could be because it is playing a longer game in the international legitimacy stakes. Attacks on UN human rights monitoring may bring the government short-term condemnation from those nations fashioned as the international community, but these storms can be weathered by growing Chinese financial and diplomatic support which is not tied to human rights obligations (although it comes with other strings).

In the longer term, a weaker UN human rights regime in Cambodia could lessen the frequency and the volume of criticism targeted at the government. It also means the focus of international advocacy will be on restoring the status of the UN office rather than on the underlying human rights issues. The government has threatened to close the Cambodian OHCHR office at the end of the year if a new memorandum of understanding is not signed. It’s unlikely the government will bother to go this far, but it has made clear that human rights criticism will come at a cost.

Rebecca Gidley is a PhD candidate at the School of Culture, History and Language at the Australian National University. Her thesis examines the creation and operation of the Khmer Rouge tribunal.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss