2015 was the year authoritarian governments struck back against democratic pressures.

The story of 2015 in Southeast Asia was Myanmar’s November election. In giving the National League for Democracy and its leader Aung San Suu Kyi a landslide, Myanmar citizens signaled their strong support for democratic change and better governance.

These calls have been loud in recent years — in Malaysia’s 2008 and 2013 elections, in Thailand’s repeated electoral victories for a non-military aligned government, in Cambodia’s 2013 and Singapore’s 2011 polls as well as strong electoral support for democracy in the Philippines and Indonesia. Democratic pressures on Southeast Asian governments have been increasing, and are not likely to recede in the near future.

2015 was the year authoritarian governments in the region struck back. Behind the Myanmar headlines there is a worrying trend of a significant democratic contraction taking place. The use of the authoritarian arsenal by Southeast Asian governments are not new, but in the course of the year regional governments expanded their use of incumbency and control of institutions to shore up their positions.

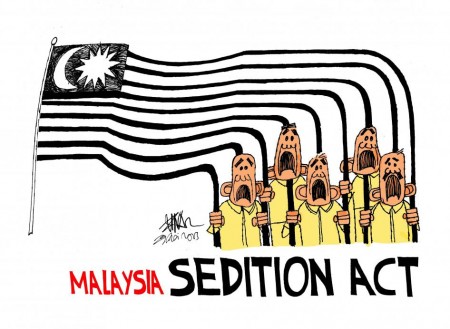

The most obvious trend has been the increased use of repression, especially targeted toward opposition politicians and critics. In Malaysia, opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim was jailed in February. In Thailand, a trial began against ousted PM Yingluck Shinawarta as she was denied the right to travel. In Cambodia, opposition politicians were physically attacked. The leader of the opposition Sam Rainsy has delayed his return to Cambodia from November as a result of jail threat. Malaysia has the highest number of opposition politicians facing various charges from sedition to violations of banking finance regulations.

The threats opposition members across the region face in calling for change extend from being physically attacked on the campaign trial (as occurred for Myanmar’s Naing Ngan Lin NLD candidate who was slashed by a machete) to potential bankruptcy.

The use of the law for political ends moves beyond opposition members. Journalists and bloggers remain targeted. Radio reporter Jose Bernardo was shot dead at a restaurant in Manila in November. He joins the other 77 journalists who have been killed in the Philippines since 1992, making this country one of the most dangerous places for media professionals in the world.

Myanmar tops the region’s list with the most number of journalists jailed, pipping Vietnam this year who released some of its bloggers. Notably, blogger Ta Phong Tan was released after 10 years in jail. The situation for bloggers in Vietnam remains serious, with a number of incidents where bloggers and associates were beaten up in mysterious circumstances rather than jailed. In Singapore, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong won his defamation case against a blogger critic Roy Ngerng, who was asked to pay PM Lee S $150,000. Lee joins Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak as the second current leader in the region who filed charges for public criticism.

The crackdowns on freedom of expression extend to ordinary citizens, from artists and academics to taxi drivers.

Young Chaw Sandi Tun was sentenced to six months jail for insulting Myanmar’s army in her Facebook post noting the similarity in color between the Tatmadaw’s uniform and the opposition leader’s clothing. In Thailand, the cases involving lese majeste have extended the boundaries to include insults to the king’s dog. Thanakorn faces up to 15 years in jail for this reference, and joins a long list of cases that have involved jailing of university students for a play, taxi cab conversations, novelists and more.

A mother of two was sentenced to 28 years for her Facebook comments, while a hotel employee received 56 years for his posts in August as part of the lese majeste unending prosecutions. Cartoonist Zunar in Malaysia faces up to 43 years for his satirical art work. These developments have had chilling effects on public discourse. Even in more open Indonesia, discussion of the 1965 attacks on communists were shut down.

As power has been used to quiet alternative voices, the rule of law itself has faced erosion. In some cases the law is not being implemented. In July, the co-Investigating International judge Mark Harmon of the Khmer Rouge tribunal in Cambodia resigned his position after the tribunal declined to arrest two former Khmer Rouge leaders for whom the court had issued warrants.

Despite having the technology to find the daughter separated from her mother Indira Gandhi for seven years by a husband who is abusing religion in a personal vendetta against his ex-wife, the Malaysian police have proven to be unwilling to use its tools to follow the court order to return the daughter to the mother.

In other cases, constitutional frameworks protecting rights have been by-passed through the introduction of military courts – as has been the case in Thailand and called for in Malaysia – and new measures that empower leaders to declare ‘security areas’ without checks on their authority, as occurred with the hurried passage of the National Security Council law in Malaysia. This law is being seen as a measure that will allow unpopular Prime Minister Najib to stay in office if he loses an election. In Myanmar, there are potential laws being considered that may give military impunity for alleged past crimes.

The area where the laws are under real scrutiny continues to be corruption. 2015 showcased some shocking scandals.

In Malaysia the 1MDB $700 million ‘donation’ into Najib’s personal accounts remains inadequately explained, as the rule of law has not been properly applied to the premier and impunity appears to have allowed the premier to hold onto office even with his personal reputation in shatters. Efforts to undermine Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) and the recent demands for payments from Freeport to politicians to conduct business have showcased that persistent problem of bribery, lack of transparency and abuse of position.

From corruption concerns tied to the Aquino administration in the Philippines to persistent effects of corruption trails associated with Vietnam’s elite, there lacks effective leadership in tackling the region’s most serious governance problem. The end effect is that leaders at the top are seen to engage in graft, reinforcing a system where office is used for personal wealth rather than public service.

Control over resources and alliances with cronies remains a dominant feature of Southeast Asia’s political economy. Four countries in the region – Malaysia (3), Singapore (5), Philippines (6), Indonesia (10) – were in The Economist’s crony capitalist list, which measures the favoritism of wealth toward tycoons and politically-affiliated business interests.

Measures to enhance this favoritism expanded in 2015 through the introduction of consumption taxes in Malaysia and Myanmar, regulations that facilitated more burning rather than less in the haze-affected region in Indonesia and service fees in areas such as tolls to crony-companies. The region’s most vulnerable populations are feeling the economic pain, with depreciating currencies and a slowdown in growth in the region as a whole. These conditions have contributed to conditions where the use of state resources through populist policies have boosted incumbent governments, a factor that contributed to the People’s Action Party’s September 2015 electoral victory.

Those on the margins are being particularly impacted, with serious implications for rights. Southeast Asia was not immune from the global refugee crisis affecting over 60 million people worldwide. Conditions affecting the livelihoods of the Rohingyas in Myanmar remain severe, with conditions in camps across the region not much better. The shocking findings of death camps in Thailand and Malaysia involving torture, rape and human and organ trafficking in May have yet to be properly accounted for.

One reason for this lack of accountability lies with the upgrade the Obama administration gave Malaysia on its human trafficking assessment in the wake of the discovery of the gruesome murders. The Obama administration’s sell out of human rights principles was especially acute in 2015, where interests associated with the Trans-Pacific Partnership overrode other concerns.

From questions tied to the trial of Burmese migrant workers in killing British backpackers Thailand to the persistent practice of ‘sea slaves’ with citizens hauled onto fishing boats, those that are vulnerable remain so at the end of the year, which limited measures to point to strengthening protections.

Vulnerability in 2015 extended to religious and ethnic minorities as well. Bogor was labeled Indonesia’s most intolerant city when it declared a ban of the Shia faith in the city. Hate speech toward Muslims persists in Myanmar, in spite of the electoral victory signaling greater inclusiveness. Churches were burned in Aceh. Christmas celebrations were banned in Brunei. Rights of religious minorities were curbed in Malaysia in cases involving child custody and worship.

Measures to forge peace with minorities fell apart, as the Philippines’ Bansamoro Basic Law did not pass the legislatures. In other places such as Myanmar, Protection Race and Religion Bills denying rights to marriage and religious freedom were introduced, as protections for rights were in fact eroded.

There were nevertheless bright spots in greater freedom across the region – a gender rights bill in Thailand, the end of the persecution of a book seller and academic by religious authorities in Malaysia, the reinstatement of direct local elections in Indonesia and the subsequent peaceful elections in December, to name but a few.

Southeast Asians continue to fight for their freedoms valiantly, over cyberspace, in courtrooms and in communities. The climate however has not been conducive to greater freedoms as those in office continue to use their offices to hold on to power.

As we look ahead, with a slowing economy and persistent insecurities by incumbents, the prospects for expanding rights does not appear promising in 2016. Last year has shown us however that we can expect the unexpected, with the military’s acceptance of the Myanmar’s electoral results as an example.

As ASEAN formally announced its community on 31 December 2015, many hold on to a potentially different ‘imagined community,’ where the ideas of brilliant scholar Benedict Anderson of shared belonging, human dignity and decency live on.

Bridget Welsh is Professor of Political Science at Ipek University, Senior Research Associate at the Center for East Asian Democratic Studies of National Taiwan University, Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Center, and University Fellow of Charles Darwin University.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss