In the wake of elections, should the world engage with Myanmar’s ‘extreme’ monks and newest political force, asks Thusitha Perera.

This Sunday’s election represents one of the most crucial times for modern Myanmar, at least within this decade.

In the long lead up to the ballot, Myanmar’s political landscape has been rapidly evolving and expanding into a vibrant and volatile mix as old fault lines subside and new ones emerge.

One new player is, Ma Ba Tha, a Buddhist movement that has sent ripples through society and generated a fair amount of discussion and commentary both at home and abroad. It’s also invited both accolades and criticism.

The praise mostly comes from Myanmar’s majority Buddhists, while criticism mostly stems from a certain section of the political opposition to which Ma Ba Tha has been an irritant.

But who are these new players, and how much do they matter?

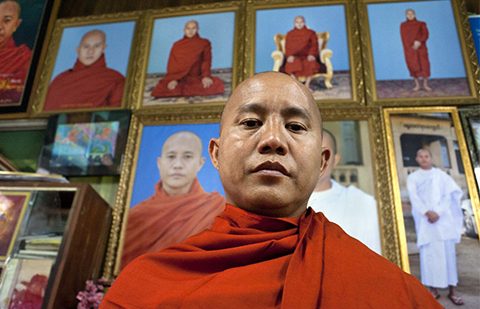

The Patriotic Association of Myanmar (abbreviated to Ma Ba Tha in Burmese) is mainly led by Buddhist monks and seen by non-Buddhists and outsiders as hardliners, at times even branded as extremists (a label that is not always appropriate).

Looking at Myanmar over the last couple of years their existence is nothing new; it has been somewhat common to see organisations of varied ideological orientations mushroom and then hibernate.

But when President U Thein Sein signed into law four bills on race and religion in Myanmar on 31 August the group propelled to prominence.

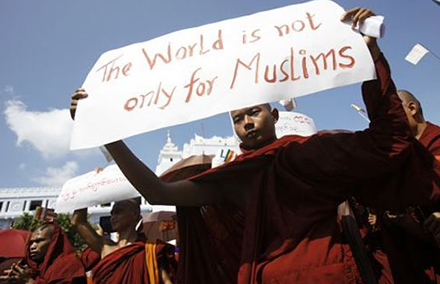

The four bills, initiated by Ma Ba Tha, are viewed by rights groups as a thinly veiled attempt to target religious minorities, especially Muslims, in Buddhist-majority Myanmar. Their passing transformed Ma Ba Tha’s image from a single-issue protest group into a much feared and respected political lobby with the ability to propose and push forward legislation.

Established two years ago, Ma Ba Tha sprang from the now defunct 969 movement, a loose collection of monks linked to a wave of violence against the country’s Muslim minority in 2012 and 2013. The 969 Movement, led by a firebrand Monk U Wirathu, left a trail of violence in its wake and commanded a visible increase in support from the country’s Buddhist majority thanks to Myanmar’s newly found freedom of expression and the lifting of media restrictions.

Senior Ma Ba Tha officials claim the 969 movement had raised awareness about threats to Buddhism from a growing Muslim population, but was disorganised and lacked leadership. It was eventually superseded. Whatever the real reasons for shutting down the 969 Movement, the rise of Ma Ba Tha signifies the emergence of a new power block within the Myanmar polity.

What the 969 movement lacked in leadership and organisation, Ma Ba Tha seems to have in abundance. It is led by a central committee composed of around 50 members; including both prominent monks and senior monks who are also part of the Government recognised State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee.

Ma Ba Tha claims it has extensive networks and chapters at state and township levels across Myanmar. A growing number of professionals are offering their expertise on everything from media relations to legislation, helping to shape Ma Ba Tha into an upwardly mobile and engaged organisation with popular support and real political clout.

A team of Ma Ba Tha associated lawyers drafted the protection of race and religion bills, a significant departure from crude and at times violent ad-hoc measures employed by its predecessor. Retired diplomats, lawyers, economists, IT experts and other professionals had made Ma Ba Tha resemble more of a tech-savvy lobby group than what one expects from a rag-tag hardliner group.

Photo: AFP

The presence of a second tier of lay technocrats highlights the future possibility of fielding candidates from within its ranks, an option a few senior Ma Ba Tha monks have hinted lately in private. However, Ma Ba Tha has shown no sign of contesting the upcoming elections itself but says it will “remind” the public of candidates who opposed its four laws – often a euphemism for threats and harassment.

And while the religious clergy has no voting rights in Myanmar – a precaution laid out by the previous military regimes – the swift passage of laws signifies that anything is possible in the current state of politics in Myanmar, provided an adequate amount of pressure is applied to the right power centres.

Along with its increasing political influence, Ma Ba Tha seems to be scaling up its public image and venturing into what could be seen as public interest activism. In early June this year, the government announced the cancellation of several construction projects bordering the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon.

The cancellations were the culmination of a mix of threats of nationwide protests by Ma Ba Tha and increased public opposition to the projects due to representations made by a civilian advocacy group attributed to Ma Ba Tha.

In early July 2015, Ma Ba Tha came into a partnership with one of Myanmar’s popular satellite television providers to broadcast its sermons. The broadcasts would help the public “know the truth” about Ma Ba Tha, claimed a statement attributed to a prominent figure within its hierarchy.

During the same month, in a widely publicised media event, Ma Ba Tha representatives signed an agreement with a Buddhist delegation from Thailand which offered the group financial support to purchase equipment and finance construction of two radio stations, signalling a widening of recognition outside Myanmar, especially among Buddhist organisations within Southeast Asia.

Buddhism has its fair share of opportunists. Just like in any other religion, its practice can be hijacked by people whose political agendas are anything but innocent. The problem with Buddhist extremism is that it is completely the opposite of what Buddha was trying to make people understand.

The modern Sangha – or the community of monks – in a majority Buddhist country such as Myanmar is faced with the challenge of a shift towards modern democracy and the growing multicultural nature of their society. The advent of democracy, or a semblance of it, has challenged relationships between formal religious organisations and the political representation of ethnic groups in Myanmar.

It also shows that the Sangha seems to draw inspiration from an autocratic past rather than acknowledging the reality of a new diverse political order.

Thus there is a greater need for political parties, civil society and the international community to find an answer to dispel this political anxiety and avert polarisation. If not, organisations like Ma Ba Tha come along, providing a platform for these political anxieties and creating extreme realities.

Understanding this anxiety will be the key in crafting effective responses on the part of international community and local civil society. Responses that combat the negative elements of Ma Ba Tha and its ideology while embracing democratic values of free expression and engagement will require a more nuanced approach in understanding the organisation and its role in contemporary Myanmar.

And the experience gained in Myanmar’s current transition holds the key in dealing with Ma Ba Tha.

While the sanctioned regime of the past drew Myanmar towards isolation from Western powers, limited but meaningful international engagement with the less hardliner elements of the same regime over recent years managed to act as a catalyst towards change.

As such, the international community should draw parallels from that experience and continue engagement and dialogue with Ma Ba Tha. This, in the shorter term, will help in understanding its aspirations and interests, while providing a certain level of confidence within Ma Ba Tha’s hierarchy to engage more with the international community.

In the longer term, such engagement will help to dispel fears of hardliner elements within Ma Ba Tha and open space for moderates within its ranks to shift towards action embedded in the Buddha’s teachings.

If Myanmar Buddhists find any movement to be a stain on their identity and belief system, then they too should respond with concepts that guide action embedded in the Buddha’s teachings. This would include excising caution in who to stand with of course.

Engaging with Ma Ba Tha and not isolating it from the wider political discourse will not only help Buddhists but all the people of Myanmar in their journey towards a better system of government and fair representation.

It is the responsibility of the international community to reach out and open the door for engagement. Recent meetings with the US Ambassador and Ma Ba Tha representatives may be a step in the right direction.

Thusitha Perera is an analyst who has been observing political developments in Myanmar since 2009.

This article forms part of New Mandala’s ‘Myanmar and the vote’ series.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss