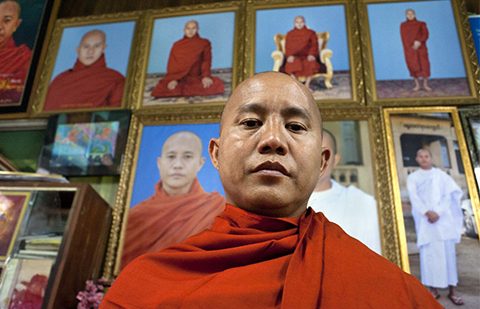

969 leader Ashin Wirathu. Photo: Al Jazeera.

Rhetoric, violence and growing influence could derail the country’s political transition.

The Association for the Protection of Race and Religion–a group of nationalist Buddhist monks in Myanmar–has been rapidly gaining political clout in recent months.

More commonly known by its Burmese-language acronym Ma Ba Tha, the group has scored several major policy victories, demonstrating the extent to which it has the capacity to influence Burmese politics as the 2015 general election approaches.

As Ma Ba Tha has expanded its reach, questions about its connections to the Myanmar government and the ruling Union Solidary and Development Party (USDP) have emerged.

Many activists contend that a working relationship between Ma Ba Tha and the current government exists, which has effectively enabled the group’s rise, allowing it to amass a sizeable following without fear of recrimination or backlash.

But while it is clear that the government has not actively countered Ma Ba Tha’s growing influence, recent developments, including the group’s campaign against a series of development projects in Myanmar’s largest city, demonstrate that its priorities are not perfectly in sync with the USDP’s.

They also raise questions about the relationship itself, which make understanding Ma Ba Tha’s true power base and the political dynamics behind its rise a challenge.

The growing influence of Buddhist extremism

Ma Ba Tha’s prominence is indicative of a growing trend in Myanmar of rising Buddhist nationalism. The group was formed in the aftermath of deadly interreligious violence in western Myanmar’s Rakhine State in 2012.

Its explicit goal was to “defend” Buddhism from a perceived “onslaught” of Islamic invaders, who, Ma Ba Tha leaders argued, sought to deprive Myanmar of its ethnic and religious identity. Since then, the group has morphed into a fixture on the political scene as the country has struggled to sustain the forward momentum of its ongoing democratic transition.

Ma Ba Tha’s main contribution to the political debate since its formation has been its effective fomentation of anti-Muslim sentiment nationwide. The group grew out of the Buddhist extremist movement known as ‘969.’ Prominent monk Wirathu–famed for his rabid anti-Muslim tirades–leads 969, amassing a sizeable following as he ratcheted up its xenophobic rhetoric.

While Buddhist monks are constitutionally barred from voting in Myanmar, they have historically wielded immense influence in the conservative majority Buddhist country. Monks led the 2007 Saffron Revolution against the then-ruling military junta, and they featured prominently in previous uprisings against military rule.

With the emergence of a quasi-democratic system, complete with a functioning parliament, Buddhist monks–most prominently those associated with Ma Ba Tha–have begun to use their power to intervene in the legislative and policymaking process, advocating for the enactment of specific laws and government policies.

“Protecting” race and religion

Key among these efforts has been Ma Ba Tha’s campaign for the passage of a set of four bills collectively known as the “Race and Religion Protection” package.

In alignment with the group’s raison d’├кtre, the bills are aimed at safeguarding the nation’s religious identity by placing restrictions on the freedom of specific classes of citizens to convert, marry, and procreate, with a particular focus on the Muslim community.

The first of these bills–the Population Control and Healthcare Bill, which enables the government to mandate birth spacing and other reproductive restrictions in specific areas of the country–was signed into law in May.

In July, Myanmar’s parliament passed a second bill in the package: the Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage Bill. The legislation places restrictions on the ability of Buddhist women to marry men of other faiths, including requiring interfaith couples to seek permission from local authorities in order to wed.

Despite outcry from prominent international voices, which denounced the Marriage Bill as an affront to women’s and minority rights, the bill passed by an overwhelming margin–524 votes to just 44 in parliament. The final two bills, which place restrictions on religious conversion and polygamy, were passed easily last week.

The lopsided vote tallies for all the bills demonstrates that few national politicians are willing to cross the powerful Ma Ba Tha lobby on issues it views as its core priorities.

Benefits for the ruling party

The widespread political support for Ma Ba Tha-backed policies among parliamentarians and government officials is also a product of the fact that the USDP and its allies stand to benefit from the group’s nationalist rhetoric.

Such rhetoric has served to heighten religious tensions, stirring up divisive nationalist sentiment that threatens to undermine opposition parties, including the National League for Democracy (NLD)–the ruling party’s biggest rival in elections this November.

In addition, although Ma Ba Tha leaders’ have claimed to be politically independent, many observers and activists have identified a mutually beneficial working relationship between the monks and the current government.

Despite Ma Ba Tha’s odious international profile as a xenophobic collection of “mad monks,” the ruling party has effectively embraced it.

Government officials have, for the most part, looked the other way when Ma Ba Tha leaders have engaged in divisive hate speech against Muslims in Myanmar, allowing this type of rhetoric to proliferate, while cracking down on individuals accused of “insulting” Buddhism.

In return, the USDP has received some direct backing from Ma Ba Tha monks. Despite the fact that monks are generally supposed to remain above the fray of electoral politics, one Ma Ba Tha leader flat out told fellow members at a recent gathering in Yangon to rally support for the ruling party in advance of elections.

“Save the Shwedagon”

In recent months, however, Ma Ba Tha’s priorities have expanded beyond its core focus on countering the Muslim “menace.” Beginning in early 2015, Ma Ba Tha engaged in a campaign to prevent the construction of a series of new high-rise developments near the revered Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon.

The monks argued that the high rises would obstruct views of the pagoda and possibly disrupt the foundations of the sacred site. In June, Ma Ba Tha threatened to lead nationwide protests if the government moved ahead with the developments.

Authorities in February had temporarily suspended the projects, but had been hesitant to scuttle plans entirely, having already inked agreements with developers. But in the face of Ma Ba Tha’s threats (in addition to a coordinated multi-stakeholder campaign) the government signed an order on 7 July canceling the high rises.

The ultimate decision was an impressive achievement for the monks and marked an important shift. It signaled a widening of Ma Ba Tha’s policy objectives.

The “Save the Shwedagon” campaign, as it came to be known, was Ma Ba Tha’s first targeting development projects, rather than the country’s vulnerable Muslim minority, and it proved that the monks have their own broader agenda.

Divergent priorities, independent power base

In many ways, the “Save the Shwedagon” campaign was a test of Ma Ba Tha’s true political heft.

Getting the government to buy into a scheme to further restrict the rights of an already persecuted minority was relatively easy. But getting an administration, which has made economic development its key priority, to backtrack on firm commitments to developers was a much heavier lift.

The campaign’s success therefore complicates understandings of the relationship between Ma Ba Tha and the current government, signaling that the organisation may be more independent and able to rely on a power base separate from its USDP allies.

The group may well continue to pursue a more independent political course in the coming months and years and emerge as an unpredictable political actor with significant popular support.

Government leaders, who’s tacit backing (or at the very least hands-off approach) has allowed Ma Ba Tha to amass a sizeable public following, likely believed that the group would remain focused on pushing for anti-Muslim policies the government had no problem enacting.

But by enabling the group’s rise, the ruling party may have unwittingly created a monster it cannot so easily control.

Understanding the political dynamics

Ma Ba Tha represents a threat to Myanmar’s nascent transition. Its extremist rhetoric heightens the risk of increased violence against ethnic and religious minorities, particularly Muslims.

The Myanmar government certainly bears substantial responsibility for increased ethnic and religious tensions as well. Its policies targeting Muslims, particularly the vulnerable Rohingya minority in Rakhine State, have fueled increasing anti-Muslim sentiment nationwide.

But while it is tempting to believe that the government created and empowered Ma Ba Tha to serve its own interests, the reality is murky and appears to be growing more complicated by the day. Evidence of direct coordination between Ma Ba Tha and the ruling party remains limited, and it is unclear the extent to which the government can really control the monks given recent developments.

Understanding this relationship will be key to crafting effective policy responses on the part of international actors and local civil society. Policies that combat the hateful elements of Ma Ba Tha’s ideology while embracing democratic values of free expression will require a more nuanced conception of Ma Ba Tha’s role in modern Myanmar.

Oren Samet is a Bangkok-based researcher and political analyst. His work focuses on democracy and rights issues in Southeast Asia, with a particular emphasis on political dynamics in Myanmar.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss