As Malaysians rally in protest in Kuala Lumpur, it is clear that the April 1st introduction of the Goods and Service Tax (GST) has changed Malaysia’s political landscape. In the last few months the Najib administration has significantly redefined the rights of citizens, reducing freedoms while simultaneously adding to their responsibilities. Valuable analyses have focused on the worrying changes in the rule of law, particularly the political use and legal expansion of sedition and the negative implications of potentially introducing hudud, but less attention has centered on the measure that arguably directly affects more people, the GST. This tax is highly contested and has the potential to serve as a catalyst for further conflict in Malaysia’s already increasingly fractious polity. For Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak, the GST has emerged as his policy Achilles Heel that has the potential to undermine his leadership.

Politically-Loaded Interpretations

There are three interrelated issues that underscore why the GST is so divisive and damaging. This first of which is the polarizing views of the tax itself. Based on the results of Asia Barometer Survey late last year (detailed below), Malaysians were evenly divided over the GST even before it was implemented, with the majority opposed to the measure. Ethnic groups were similarly divided. Majorities in all ethnic groups opposed the GST, with more Chinese Malaysians opposed compared to other communities. The divide that stands out however is partisanship, with BN and opposition supporters strongly in favor and opposed respectively. This indicates that the GST is highly polarizing, reflecting Malaysia’s deep political divisions. In fact, the views are so strong that 5.9% of Malaysians feel that the GST is among the most important problems facing the country.

| Favor GST (%) | Oppose GST (%) | Decline Answer/Don’t Know | |

| All Malaysians | 40.0 | 56.7 | 3.3 |

| Malays | 45.8 | 51.8 | 2.4 |

| Chinese | 28.3 | 66.2 | 5.5 |

| Indians | 39.8 | 57.0 | 3.2 |

| Others | 44.5 | 53.9 | 1.6 |

| BN Supporters | 53.2 | 44.1 | 2.7 |

| Pakatan Supporters | 18.6 | 79.8 | 1.6 |

| Undecided | 31.3 | 63.9 | 4.8 |

Source: Asia Barometer Survey, Malaysia Third Wave

The interpretations of the GST have been politicized in other ways as well, with racial politics at play. For some Chinese, the GST is portrayed as Malays finally paying their dues. For some Malays, the GST has been painted as getting at Chinese who have purportedly evaded taxes. These misperceptions have been fed by years of negative stereotyping. The racial mobilization around GST has gone further, with the government attempting to deflect the blame for the policy on others. Within UMNO, there has been a campaign on the ground, especially in the heartland, to lay the blame of the GST on the supposed ‘exploitation’ of the Chinese middlemen and traders. All of these lens reflect the ethnic fragmentation of Malaysia, point to the continued attempts to divide Malaysians along racial lines, and to blame other communities rather than the government for policies. They also reflect the persistence of the mobilization of race for political ends.

If the racial dimensions of the GST were not enough, there has been a religious heuristic as well. The GST has been labeled ‘haram’ and officially in a fatwa as ‘halal’. Some religious figures have gone as far to call for Muslims who already receive considerable tax benefits by being able to write off their zakat contributions on their taxes (often well beyond the legal 2%) while other faiths lack this right, to excuse Muslims from paying the GST. This development reveals not only how much religion has become part of Malaysia’s political fabric, but shows that some Malaysians Muslims do not believe they have a responsibility to the nation as a whole. The religious divide is even more cutting, in that it is cloaked in a false sense of ‘morality’ that has lost any real sense of justice and community.

As the tax has come into effect in the last month, the interpretation that has resonated the most is that the Najib government is taking from the people. With views extending from ‘robbery’ to grudged acceptance, the public is now aware of taxation more than ever before and sentiment is overwhelmingly negative. This ‘forced marriage’ (to coin the label of the GST given by UMNO veteran leader Mohd Ali Rustam) has led to greater reflection of what is being paid and what is being delivered by government, with the dominant view that the government is falling short in delivery and even ‘uncaring’. Najib’s close association with the GST has led to him receiving the bulk of the blame and reevaluation of governance, with views of his leadership becoming increasingly antagonistic. The premier now has the lowest popularity rating of any of his predecessors, to the extent that his presence has been intentionally minimized in the country’s ongoing by-elections.

Burden Transfers: Tax Incidence

The divisive perceptions of the GST are enhanced by debate over who pays taxes generally and who will bear the burden of the GST. Any reliable analysis of tax incidence requires detailed household information and greater transparency in data than currently is available in the public domain. Twenty years ago there were regular published works on tax incidence by class and race in Malaysia, but today these are in short supply, and estimates have to be made with what little information is available.

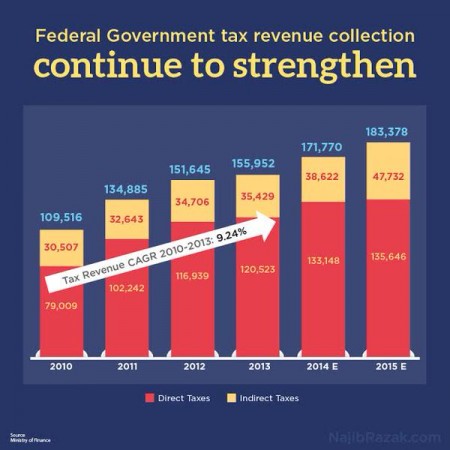

Malaysia stands out in the region for its relatively low payment of direct taxes. According to published figures by the Department of Statistics in 2013, less than three million taxpayers paid income tax, or roughly 22% of the labor force. A higher percentage of corporations pay, especially local businesses that do not have the lucrative benefits of the tax incentives and foreign multi-nationals who adeptly use loopholes to avoid tax. In 2013, 261,000 businesses paid taxes, roughly 25% of registered companies. The amounts paid by business reach a share of GDP in line with rates in OECD countries, but the actual number of payees of both individuals and companies is comparatively low. This is compounded by the fact that there is considerable tax evasion. Despite the vigilant efforts of Malaysia’s Inland Revenue, there remains serious gaps in collection, as there is systemic underreporting, and capital flight. Nevertheless, direct taxes comprise nearly 80% of national tax revenue. Proponents of the GST have argued that indirect taxation is needed to address the shortcomings in direct taxation. This has underscored the rally toward the most popular form of indirect taxation, the GST.

Indirect taxes have long been an integral part of Malaysia’s tax regime, from ‘sin’ taxes on liquor, and cigarettes inherited from the colonial era to the sales and service taxes introduced in the 1970s. Before April, the sales and services taxes have been limited in scope, concentrated on particular goods such as imported cars and a narrow range of services. The introduction of the GST significantly widened the scope of items subjected to the 6% GST tax. Now indirect taxes affect everyone, assuring that the 78% of individuals and 75% of companies not taxed directly are now contributing to government coffers. Premier Najib has already tweeted that there is will be estimated 35% increase in the revenue collected from indirect taxes, to reach RM47.7 billion this year.

The widening of who pays indirect taxes has sparked public debate. The focus has been the impact on those with lower incomes, as a majority of Malaysians earn incomes of less the RM4,000 monthly. Competing studies by the government and DAP-government’s Penang Institute last year argued over the monthly costs imposed on those most economically vulnerable. They differed in the amounts (and their studies are now irrelevant as the list of exemptions/zero rated items has changed), but both agreed that those with lower incomes would now be part of the country’s tax base.

The GST is a regressive tax, and although there are exemptions and zero-rated items, there is no getting away from a higher tax burden in everyday life. Malaysians have experienced this over the last month. A 6% increase in costs has already brought an additional tax burden on ordinary citizens, even with the exemptions. With Malaysia’s household debt at over 80%, one of the highest in the world, this burden has been especially hard for those living on the financial edge. The long-term ramifications remain unknown. These added financial pressures from the GST on the majority of Malaysians have the potential to contribute to rising indebtedness and strains on families to increases in crime and add to the tensions in society as a whole. Independent studies are needed to measure the socioeconomic effects.

The widening of Malaysia’s tax burden has nevertheless resonated politically in a short time. This tax has especially hit UMNO’s political base. Disproportionately the incumbent government receives its political support from the lower classes, many of whom have not paid taxes in this level before, or ever. Many of those in favor of the GST initially are no longer as positive. The GST is thus not only a seismic shift in the relationship between the Malaysian government and its citizens, it has become a major shift in the dynamic between UMNO and its supporters. This is one of the reasons why veteran UMNO politicians – including former premier Mahathir Mohamad – are openly calling for the GST not to be implemented. They are worried about the potential losses for UMNO from GST under Najib’s leadership. As the fuel subsidies did for his predecessor Abdullah Badawi, the GST serves as a rallying cry against Najib within his own ranks.

To understand Najib’s GST initiative one has to step back and look at his economic management and outlook. Najib has depended heavily on foreign advisors in shaping his economic policy, and appears to follow their ideological lens. The Najib administration has worked hard to conform to external orthodox expectations, with the hope that this will attract capital and strengthen Najib himself. Following the right–wing Margaret Thatcher who nearly doubled England’s VAT from 8 to 15%, Najib believes that the GST as a needed measure to assure that those with capital can drive the economy. He argues that the GST will increase GDP growth, although the more common pattern is an initial slowdown in an economy. He has indicated that the GST will rise to 10% in the coming years. He has coupled the introduction of the GST with a promised reduction in the corporate tax rate next year – fitting this neo-conservative policy paradigm.

This Thatcherite view of economic growth is not going down well at home. Najib is increasingly perceived as taking from everyone but giving breaks to a few. This perception reinforces the perception that his government is for the rich, not the struggling middle and lower classes. This image is enhanced by the reported wealthy lavish lifestyle of Najib and his immediate family. As Mahathir’s nationalist campaign against the premier has gained traction, Najib has been quietly portrayed as appeasing foreigners at the expense of Malaysians.

One irony of the GST is that it is being introduced at one of the weakest points in Najib’s tenure. His leadership is currently tainted with arguably the worst and most expensive corruption scandals in the country’s history, with a number of these (notably 1MDB) negatively affecting the country’s financial credibility and revenue position. Concerns have also been raised about public debt. His premiership has spent (and borrowed) the most money to shore up his political support, reflecting his insecurity as a leader. There is a genuine need for more money in government coffers, but public confidence in how it will be spent is low. There is even lower confidence in Najib’s leadership over the spending. Najib’s efforts to win foreign investor support by introducing the GST is not gaining the ground he expected.

Questions of Competency: Flawed Implementation

Despite the political criticism surrounding the GST, there are strong supporters of the measure, who see the tax as part of the modernisation of Malaysia’s taxation system and place less emphasis on the transfer of the tax burden. They see this as a needed and justified reform. They argue correctly that good implementation of a GST can indeed ameliorate the most serious socio-economic effects of a GST, especially if these measures are coupled with other policies that widen the social safety net. Yet, this is not what has happened to date under Najib’s administration of the measure. In fact, as noted by UMNO veteran politician and former trade minister Rafidah Abdul Aziz, the problems in GST implementation are serious. This is arguably the most damaging for Najib, as he is the minister in charge of finance.

The administration was given eighteen months to prepare for GST. Every country that implements the tax has teething problems, but Malaysia’s problems go beyond the norm. Almost one month after the GST was introduced, Malaysians still do not fully know what is or isn’t taxable. As the parody Cantonese song by Eugene Chung reveals, confusion reigns. A proper list of zero-rated and exempt items was not circulated before implementation and even now (one month later) there are contradictory reports. Inadequate preparation was spent on educating the public and communicating the tax to the public. The public relations campaign concentrated on shoring up support for the tax itself, in a RM2 million cartoon campaign, rather than engaging businesses and citizens on the fundamentals of the GST.

The citizen education effort was hampered by delays in settling the list of items, which were being negotiated and changed in the days prior to the GST introduction. These negotiations, behind closed doors and without public accountability, have contributed to Malaysia’s list of zero-rated and exempt items not conforming to international standards, a dimension that has added to the confusion over the GST itself. Questions are also being raised about who was able to secure exemption and why, given the anomalies. The persistent debate among ministers in the government itself over who has to pay what, in areas such as phone charges, highlights the unresolved mechanics of the GST.

The public was not properly brought into the GST implementation. The lack of adequate public consultation on the GST is evident with the confusion over the ‘service charge,’ a measure that companies have used to provide compensation for workers but has been interpreted as ‘services.’ Debates have addressed whether the service charge should be subject to the 6% GST. The problem is not just about the service charge itself but the way in which many companies pay their employees, as they have used the ‘service charge’ to keep wages low. The public (including businesses) is confused on what is to be paid and why.

This is compounded by a lack of understanding in some of the administrative departments themselves. When citizens and businesses call the Custom’s Department’s hotline for answers, they are not getting the answers they need. There is often general knowledge on the line, but there are difficulties in getting answers to technical questions, especially from Malaysians who do not speak Malay. The training and preparation to handle the public enquiries could have been improved, as this has contributed to frustrations. Questions are being rightly asked whether the Customs Department is the right collecting body, or whether the collection might have been better served by coming under Inland Revenue.

Legitimate concerns also have been raised about implementing GST at this point of time, when the region’s economy and Malaysia’s economy have been slowing down. Similar issues have been raised about coinciding the GST with rises in transportation costs. The government’s introduction of the policy did not coincide with any meaningful measures of offset the burdens on citizens. This timing of the policy introduction appears not to have been assessed holistically.

The flawed implementation has raised fundamental questions of preparedness. Najib has claimed that studies were done to assess the GST. These studies have not been properly shared with the public, or debated in parliament. One alleged study is based on year 2000 numbers, using fifteen-year old projections to analyze the impact of the GST. It is little wonder there are comprehension challenges. There appears to be a deficit in studies looking at important questions associated with the GST – the impact on small businesses, the impact on growth in the economy, the disparate effects on different communities, including women and East Malaysians, the relationship with other policies such as the fuel subsidy removal and distribution of BR1M payments. Importantly, there has been no connection of the GST with the social safety net or public discussion of the transfer of the tax burden on citizens.

To make matters worse, the implementation focus has been on punishment of those who do not conform to the GST. Rather than spend more funds on public education, allocations have been primarily allocated to enforcers, with fines already imposed on confused businesses. The structure put in place for payments for Malaysia’s GST is extremely burdensome, requiring payments twelve times a year rather than the international norm of quarterly. The penalties are harsh at RM100,000, including multiple high fines for each payment period and jail time. Practically, these many points of engagement with enforcement increase the potential for corruption and avoidance rather than encourage revenue generation and public cooperation.

Poor implementation of the GST already accounts for the negative effects on small businesses, with sundry shops, traditional retailers and small hawkers closing down. The media is full of stories of closures, with the overall numbers increasing as the October business compliance date arrives. Most of these closures are the product of poor communication about the GST itself. This dynamic has hurt local communities, who now have to rely on more impersonal outlets for their medicines and provisions rather than their neighbors.

From communication and consultation to preparedness and timing, Najib’s poor record in implementation has enhanced frustrations. Of all the issues of ineffective implementation, the one that is affecting Malaysians the most is the use of the GST to increase prices. While Asia as a whole experiences deflation, Malaysians are now facing the worst level of inflation in over three decades with unofficial estimates reaching as high as 20%. The inflation rate is a highly contested number in Malaysia as a result of how it is calculated, with many of the exempt and zero-rated items included, but the number that matters most is ordinary perceptions. This are sadly high. There are major discrepancies in the prices charged post-GST well beyond the GST levels. The Federation of Malaysian Consumers Association (FOMCA) has highlighted this regularly in reports, stating that this is ‘unacceptable’. From the fees of foreign workers to send remittances moving from RM8 to RM11 ‘due to GST’ to the sticker shock on groceries and food, often coupled the smaller portions, individuals and businesses alike are struggling to deal with this more expensive reality. Some of the price increases are due to higher inputs and relatively low profit margins, but there are many incidents of companies taking advantage of the GST to increase profits without effective oversight by the government. The Najib government is ultimately being held responsible. The GST has translated in a loss of support for Najib on multiple fronts.

Each bill, each charge, each fee all at 6% or above are reminding Malaysians of their contributions as citizens and putting Najib into the spotlight. Views of government and governance and questions of rights and responsibilities are changing. Increasing taxes in Malaysia historically served to provoke rebellion in 1895 in Pahang, 1915 in Kelantan, 1929 in Terengganu and more. Time will tell whether Najib’s GST will have a similar response, but the reality is that one month after the GST implementation the grumbling has gotten louder, protests over taxation and governance have started, and the GST has become the main policy issue of Najib’s tenure. In contrast to the flexibility and increased opportunities the introduction of indirect taxes usually provide for leaders globally, the GST has become a problem for Najib and this problem is only likely to intensify as the politics surrounding the measure grow more contentious.

Bridget Welsh is a Senior Research Associate of the Center for East Asia Democratic Studies of the National Taiwan University where she conducts research on democracy and politics in Southeast Asia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss