Let’s get one thing out of the way: fellow New Mandala contributors like Ed Aspinall, Marcus Mietzner, David Bourchier and Simon Butt were dead right when they said that a Prabowo Subianto victory threatened to put Indonesian democratisation into reverse gear. Prabowo’s behaviour after his loss in last month’s presidential election should convince us that he is remarkably quick in attempting to delegitimise independent institutions that don’t give him what he wants. It’s not unreasonable to expect that this behaviour is a sign of what Indonesia would be in for had he been elected president, and the voters made the right choice on 9 July.

Understandably, some of the post-election commentary has portrayed the Jokowi victory as a conscious endorsement on the part of the voters of continued democratisation–and, corollary to this, a conscious rejection of a more authoritarian path. Elizabeth Pisani wrote in the New York Times, for instance, that Indonesian voters ‘resisted cheap nationalist rhetoric to safeguard their democratic rights’, arguing that their preference for Jokowi ‘suggests that Indonesians will defend their democracy’. Many other authors, including Aspinall and Mietzner themselves, rightly noted that the voters had ‘chosen’ to safeguard the system.

But while the voters have in effect chosen to stay on the democratic path, did they know what they were doing at the time? There’s a subtle but crucial distinction to be made here.

We think the first nationwide survey which compares how Jokowi and Prabowo voters view democracy should prompt a bit more caution about what we can conclude about voters’ views of democracy based on the election results alone. The poll by Saiful Mujani Research and Consulting asked questioned about attitudes towards democracy, how it is has performed in Indonesia, and impressions of the country’s overall political and economic direction. The poll had a nationwide, randomly selected sample of over 1,000 voters and was in the field from 21 to 26 July.

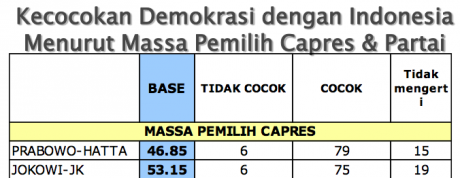

What would we be looking for in SMRC’s data to back up the claim that the electorate divided on the question of preserving democracy? We may expect, for instance, that those who express dissatisfaction with Indonesia’s current system, or with democracy in a generic sense, would be more likely to pick Prabowo. We may expect the small percentage of Indonesians who believe that democracy is ‘not suitable’ for Indonesia to gravitate towards Prabowo and his idea of a more ‘culturally appropriate’ political system. Those who felt that the Soeharto era was sufficiently ‘democratic’, in addition, may also have been disproportionately keen to vote for one of the late dictator’s henchmen.

None of these things are evident in the data published by SMRC. Indeed, it seems that there’s little difference in the level of support for democracy between the two candidates’ respective voters. In question after question, the responses of Jokowi and Prabowo voters are remarkably similar in terms of their outlook on democracy, the economy, and general direction of the country. In other words, a Prabowo vote was not a protest vote, or at least no more so than a vote for Jokowi. A majority of voters seem to be satisfied with the political and economic status quo. And the roughly one third of Indonesians who are unhappy with that status quo split evenly between the two candidates.

The table below even shows that Prabowo voters in SMRC’s sample were slightly more likely to state that democracy was ‘suitable [cocok] for Indonesia’ than Jokowi voters. (Of course, there could be different ideas about what ‘democracy’ is between these two groups of voters. But when asked whether they thought the New Order was ‘democratic’, for instance, there was also little difference in the answers given by Jokowi and Prabowo voters.)

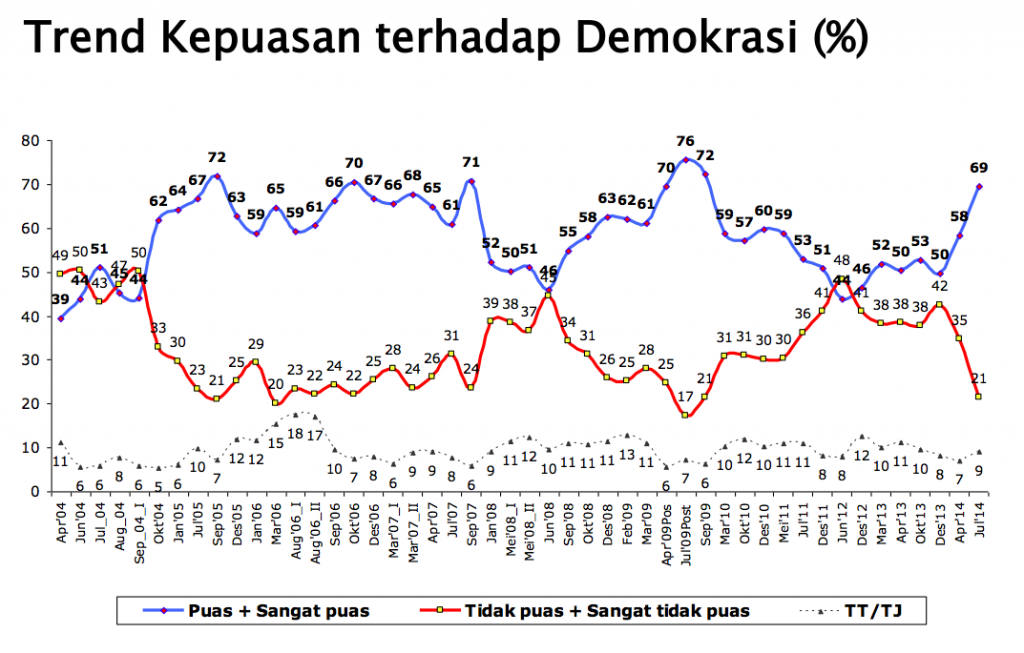

Of course, while surveys are the best way for us to measure attitudes across the entire electorate, we should be cautious of their shortcomings. For example, the graph measuring Indonesian’s satisfaction with democracy indicates that satisfaction with democracy dropped sharply only two times since 2004; in June 2008 and June 2012:

At both of these times the government attempted to reduce the costly fuel subsidy, leading to sudden increases in the price of petrol. That something as trivial as an increasing petrol price appears to lead Indonesian’s to express a lower satisfaction with ‘democracy’ should prompt caution in inferring a commitment, or lack thereof, to the actual elements of democracy such as civil liberties or free and fair elections. Indonesians’ commitment to the actual institutions and processes of democracy can only be determined by asking more precise question–do you support the direct election of the president? Do you support the separation of powers? and so on. (Polling consistently shows that Indonesians are enthusiastic about direct elections and some of the fundamentals of liberal democracy).

If we seem a bit unsure of what to make of the SMRC data it’s because we are. The first post-election survey, interesting as its results are, still leaves the question of why 47% of Indonesians voted for Prabowo unanswered. It appears that to the extent that voters saw a stark difference between the two candidates, it was to do with their personality or their campaigning style rather than their democratic credentials. Observers rightly declared with alarm that Indonesian democracy was at stake in last month’s election. But maybe we should consider the possibility that the situation was even more worrying: that July’s election was a referendum on an authoritarian reversal, and the voters didn’t realise it.

……………

Liam Gammon and Dominic Berger are PhD candidates at the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss