Indonesia’s legislative elections are now in ‘masa tenang’, or the quiet period. This means no more campaign activities until voting day on April 9. So over 200,000 caleg (calon legislatif or legislative candidates) all around the country can finally put their feet up. Many are in need of serious respite from the financial and emotional strain of the campaign trail. In fact, newspapers are saying that hospital staff around the country are preparing for an influx of caleg with post-election depression.

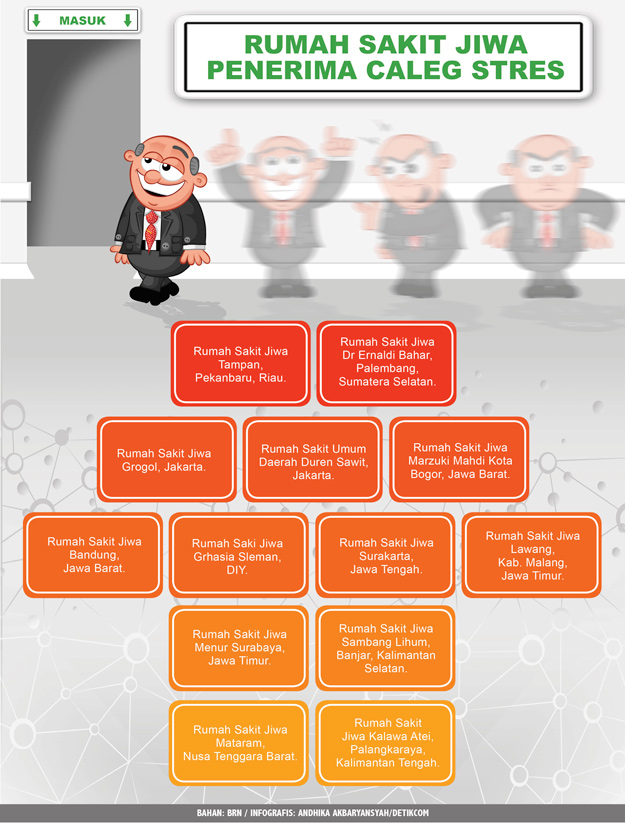

Helpful information for losing candidates? The caption “Psychiatric Hospital: receiving stressed candidates” is followed by a list of mental health institutions throughout Indonesia. Graphic: Detik

According to Tempo, the average campaign for the national legislature can cost a candidate anywhere between Rp780 million and Rp1.18 billion, which is about $74,000 – $112,000 (Aud); for the regional legislature, Tempo worked out the average cost to be about Rp320-480 million.

A caleg I met in Southeast Sulawesi, one with significant personal funds gotten from Sultra’s recent nickel boom, has spent upwards of 2 billion rupiah or around $190,000 (Aud). He sold off some of his mining assets in order to fund the campaign – and this is in one of Indonesia’s more isolated, under-populated regions. Other sources report caleg spending as high as 5-6 billion rupiah. Why does campaigning cost so much?

An incredible amount of organisation goes into legislative campaigns. Even at the level of city legislature in the humble town of Kendari, Southeast Sulawesi, candidates hire professional political consultants to run their campaigns. A consultant’s job is to design campaign strategy and help the candidate identify the right people in each village or camat who can mobilise supporters. These guys are the ‘brokers’. Brokers connect the candidate to specific parts of the electorate. They are paid to expand candidates’ network of supporters and secure votes. Consultants and brokers are also often tasked with bringing together a team of volunteers, sometimes hundreds of them. And even these ‘volunteers’ are paid a stipend.

One Demokrat candidate for Southeast Sulawesi’s provincial legislative assembly hired over 400 volunteers stationed in strategic villages throughout his electorate. Their job was to organise community events for the candidate, hand out campaign paraphernalia, and often distribute cash and staple goods as well (Indonesian laws prohibit candidates from distributing money or materials directly to voters, so these volunteers are a neat loophole)

A Gerindra candidate had a team of foot soldiers who were given lists of all the voters in their area. They worked with the candidate and his strategists to identify residents that had been snapped up by the competition, and those who were still ‘abu-abu’ – ‘grey’ or unaligned voters. These vast teams are hired many months, sometimes over a year, in advance. Collectively, the consultants, brokers and volunteers make up the candidates’ campaign team – and they all need to get paid.

But brokers can betray, to use Aspinall’s term, and their loyalty is a source of serious anxiety for caleg. I asked one candidate how he could possibly know whether his 400+ volunteers were doing any work? He basically had to compile a team of monitors. Trusted family members and friends would intermittently visit villagers and check how often Demokrat representatives were paying visits; were they distributing goods on time and to the right voters; had any team members been seen working for other caleg?

Many candidates spoke of the dilemmas they faced in hiring trustworthy team members. One caleg said that brokers would happily take her money, while actually working for someone else, and in the end deliver no votes to either party. The risky business of choosing brokers, she said, was the most stressful part of her campaign. It’s no surprise that caleg might try to limit membership of their campaign team to close family and trusted friends.

Given that parties don’t offer financial support to their candidates, each must find their own sources of funding. The pressure to run a professional campaign pushes candidates to borrow money from family members and banks. Many lobby businesses for donations in return for political favours later down the track. The debts must then be settled after the elections – win or lose. And of course there is no assurance that financial transactions will yield results at the ballot box.

So while caleg spend huge amounts of money securing the allegiance of campaign teams and voters, these efforts are often undermined by cross cutting loyalties and predatory brokers. Under these conditions, it’s no wonder Indonesia’s hospitals are bracing themselves for a flood of rejected and indebted caleg.

………

Eve Warburton is a PhD candidate at the Department of Political Social Change at the Australian National University. She is currently conducting field work in mining regions as part of her research on the politics of resource nationalism in Indonesia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss