Received by email:

Joint Appeal co-authored by Asian Forum on Human Rights and Development, Clean Clothes Campaign, Front Line Defenders, International Federation for Human Rights, Lawyers’ Rights Watch – Canada, Protection International, Southeast Asia Press Alliance, and World Organisation against Torture)

15 November 2011

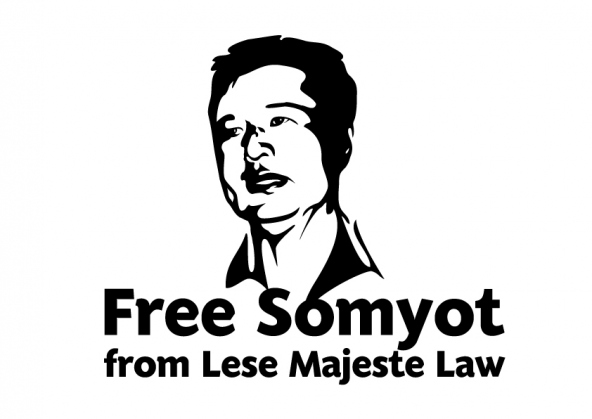

Re: Thailand – Human rights defender and magazine editor Somyot Prueksakasemsuk faces lèse majesté charge

We write to you to raise our concerns about the situation of human rights defender and magazine editor Mr Somyot Prueksakasemsuk, who will stand trial on charges of lèse majesté from 21 November 2011 until 4 May 2012. Somyot Prueksakasemsuk is a longtime labour rights activist and is affiliated with the Democratic Alliance of Trade Unions. He is facing a maximum of 30 years’ imprisonment if found guilty.

Somyot Prueksakasemsuk, who is also editor of Voice of the Oppressed (Voice of Taksin), was arrested on 30 April 2011 at Aranyaprathet district, Sa Kaeo Province, and charged with contravening the lèse majesté law or Section 112 of the Thai Criminal Code which states that “whoever defames, insults or threatens the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent, shall be punished with imprisonment of three to fifteen years”. He was detained in Bangkok Special Prison and was reportedly transferred to Sa Kaeo Provincial Court on 12 November 2011. He has been in pre-trial detention for six and a half months since his arrest by Department of Special Investigation officials in April 2011. His fourth bail request was denied on 1 November 2011.

Somyot is known for his active support for the empowerment of the workers’ movement and the right to freedom of association both in Thailand and internationally. Somyot’s arrest on 30 April came only five days after he held a press conference in Bangkok launching a campaign to collect 10,000 signatures to petition for a parliamentary review of Section 112 of the Criminal Code, which Somyot claims contradicts democratic and human rights principles. According to a document produced by the Public Prosecutor, Somyot is alleged to have allowed two articles that made negative references to the monarchy to be published in his magazine.

The hearings involving the Prosecution witnesses will take place on 21 November 2011, 19 December 2011, 16 January 2012, and 13 February 2012 in the provinces of Sa Kaeo, Petchabun, Nakorn Sawan, and Songkla, respectively, while the Defence witnesses will be called to appear before Bangkok Criminal Court on 18-20 April 2012, 24-26 April 2012, and 1-4 May 2012.

We are concerned that the venues of the hearings for the Prosecution witnesses are all held outside Bangkok in different provinces across the northern, northeastern, and southern provinces of Thailand, which will place an undue burden on Somyot and his family and undermine his fair trial rights. This may also prevent the full presence and participation of trial observers, diplomatic corps, and journalists.

We are further disturbed that if Somyot’s application for bail continues to be denied until the conclusion of the trial, he will have been in prison for over a year before a verdict is reached, since the trial is expected to last until at least 4 May 2012. This is in violation of the constitutional guarantee for a right to bail under Section 40 (7) of the 2007 Thai Constitution, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) which Thailand has ratified, and Principles 36-39 of the Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (1988).

The Truth for Reconciliation Commission of Thailand (TRCT), in its second report, also emphasised that “a temporary release…is a fundamental right of accused persons and defendants in order to enable accused persons and defendants to defend their cases, to prove innocence and to reduce effects from the restriction of freedoms on themselves and families.” Under national and international law, the right to bail can only be restricted on limited and precisely defined grounds. The authorities have yet to provide an adequate justification for his continued detention or an explanation as to why less restrictive and non-custodial measures are not sufficient to ensure his appearance at trial and non-tampering with evidence.

Our organisations are alarmed by the escalating cases of using lèse majesté law against human rights defenders and dissidents in the years following the military coup d’etat in 2006. Concerns have already been raised, in particular regarding the ongoing case of Ms Chiranuch Premchaiporn, Executive Director of Prachatai and a media rights advocate, who is also charged under the lèse majesté law and the 2007 Computer Crimes Act.

On 10 October 2011, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Frank La Rue, urged Thailand to urgently amend lèse majesté laws (Section 112 of the Penal Code and the 2007 Computer Crimes Act)*. As emphasized by the Special Rapporteur, “[t]he threat of a long prison sentence and vagueness of what kinds of expression constitute defamation, insult, or threat to the monarchy, encourage self-censorship and stifle important debates on matters of public interest, thus putting in jeopardy the right to freedom of opinion and expression”.

Concerns regarding lèse majesté laws were also raised during the consideration of the situation of human rights in Thailand through the UN Universal Periodic Review in Geneva on 7 October 2011.

We call on the authorities in Thailand to:

- Immediately drop all charges against Somyot Prueksakasemsuk, or else, grant him the right to bail in accordance with fair trial standards under domestic and international law;

- Review the lèse majesté law to ensure its conformity with Thailand’s international human rights obligations, as recommended by the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and immediately drop all charges against human rights defenders based on these laws;

- Guarantee in all circumstances that all human rights defenders in Thailand, especially those working on freedom of expression, are able to carry out their legitimate human rights activities without fear of reprisals and free of all restrictions, including judicial harassment.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss