Part I of a three part series, Crossing Borders: Chinese Agricultural Investment in Southeast Asia, this post looks at rubber plantations in northern Burma. In coming weeks parts 2 and 3 will examine similar issues in northern and southern Laos.

While Kachin State in northern Myanmar/Burma (hereafter Burma) received international attention for the rampant logging and cross-border timber trade in the early to mid-2000s (see Global Witness reports here), a very different scenario now engulfs these Himalayan foothills at the end of the decade. Instead of tripping over logs and being run down by timber trucks crossing into Yunnan like when I was conducting research there in the mid-2000s, I now find myself tripping over barbed wire. The Myitkyina / Waingmaw valley is being squared off into barbed wire plots, some with newly planted rubber seedlings, while others are just being emptied of paddy stalks, forests, firewood and farming hut platforms.

Fig 1: Newly fenced off valley land for a private company near Myitkyina, Kachin State (Source: Anonymous Kachin researcher. All other photos by Kevin Woods unless otherwise stated).

Kachin no longer speak of the livelihood hardships and ecological concerns from their forests being ripped out. They now have a more immediate and far-more worrying concern: losing their land.

Fig 2: Barbed-wire marking off a new private rubber concession in a farmer’s swidden field in the hills of eastern Kachin State.

Previously Kachin villagers had to cope only with their easily-accessible, productive paddy land being forcibly confiscated from Burmese military battalions as part of the soldier’s food self-sufficiency strategy. Or government agencies transforming villager’s fields into model demonstrations farms, seed production areas and field testing sites. In the past few years, however, a new threat has rolled into town: Burmese and Chinese state-backed agribusiness(wo)men. Private cash crop plantations, especially (but not only) for rubber, has left villagers and local development NGOs in the north scrambling to protect villager’s land and livelihoods.

Fig 3: A new Chinese rubber concession complete with brick wall and unwelcoming gate in eastern Kachin State.

In November 2010 a report was released by Transnational Institute (TNI) – the impetus for this series – that critically evaluated China’s opium crop substitution policy as a form of what is known in the drug policy sector as ‘alternative development’, or integrating (ex-) illicit farmers into the regional economy by planting legal crops (see report here).[i] Weiyi Shi’s 2008 report with GTZ on the rubber boom in Luang Namtha (see report here) has also helped to situate the rubber boom since the mid-2000s in northern Burma and northern Laos in relation to China’s political economy.[ii]

The Chinese central government encourages companies, backed with state subsidies, to invest in agricultural development overseas. Chinese overseas agribusiness ventures cultivate crops for import to China under a state-sanctioned quota system which nulls any import tariffs, making these investments more profitable and thus desirable among companies. As I explain below these sweeping regional economic transformations become grounded through a complex assemblage of legal and regulatory state mechanisms and physical force, bound together by transnational finance capital.

China’s opium substitution programme plays a very significant role in upland land investment in both northern Burma and northern Laos today. Beginning with several small-scale projects in Mongla in north-eastern Shan State (Special Region 4) in the early 1990s, the program was revamped in 2005 when it was placed under the Ministry of Commerce, to be implemented through the Yunnan Provincial Commercial Department. Since 2006 – the same year rubber cultivation spiked in Burma and Laos – Chinese business(wo)men have been spearheading these poppy substitution projects, instead of operating through Chinese government channels as before.

Fig 4: New opium fields in Kachin State along the Yunnan border (Commons).

The degree to which state subsidies to Chinese agribusiness(wo)men is a driving force for large-scale agricultural concessions in northern Burma and northern Laos is subject to debate. Weiyi Shi writes, ‘Almost all large-scale, formally organized Chinese rubber investments in northern Laos work under the directive of opium (or poppy) replacement…’ (2008:21). Chinese and Burmese central government quantitative data clearly demonstrate a spike in rubber establishment starting in 2006 – the same year that the Chinese subsidy was widely available – and has since been increasing. However, many other causal factors continue to play an important role in facilitating Chinese agricultural development in the region, with China’s poppy replacement policy – as Weiyi argues – only helping to accelerate industrial agricultural development in northern Burma and Laos, rather than acting as the sole causal agent. The increasing Chinese demand for land plays an essential part in this new political-economic dynamic, along with ADB’s GMS infrastructure development, other subsidies by foreign and national governments, domestic laws and policies, etc.

According to field research I have conducted over the years in Kachin State, and most recently northern Shan State, no smallholders are able to plant rubber due to political and financial constraints. Rather, only private Chinese companies, and to a lesser extent local ethnic Burmese businessmen (e.g. Wa and Kokang), often backed by Chinese investors, obtain rubber concessions. Land concessions influence regional political relations and related practices of territory-making in Burma. Comparing the processes and outcomes of concessions awarded in different parts of northern Burma (i.e. territories controlled by government, pro-government militias, ceasefire groups and insurgents) can help to shed light on the dynamic relationship between agricultural investment and concession politics. The manner in which the contracts are agreed, the conditions under which the crop is cultivated, labor used, and the profit-sharing agreement are informed by, and in turn influence, the political landscape in which the concessions are located.

Fig 5: Rubber seedlings sweeping across undulating hills of Kachin State.

For example, the Kachin, who reside in both Kachin State and northern Shan State, have long resisted the Burmese state, with the Kachin Independence Organization/Army (KIO/A) leading organized ethnic revolt against the Burmese military-state. However, the KIO now only administers a rather small wedge of territory along the Yunnan border, with the rest of Kachin State under the control of the Burmese government or other pro-government militias and ceasefire groups. And since the lead-up to, and the aftermath of, the national elections in November 2010 the KIO are under heavy pressure to surrender, with the imminent threat of renewed fighting since the ceasefire accords in 1994. At present many Kachin villagers feel they are without any political representatives who could effectively control and regulate Chinese agricultural investment. Indeed Kachin villagers often tell me that their increasing animosity against both Chinese businessmen and the military government over the extensive allocation of large agricultural concessions in their territories is based on widespread suspicion that the Burmese junta is using large-scale land concessions as part of a military strategy.

Kachin and other ethnic farmers are also not able to take advantage of wage labour opportunities in the private agricultural sector, which has become another point of local contention. Instead, traditional leaders and local development NGOs discussed with that Burman (the ethnic majority of the country and the ethnicity of the ruling generals) migrant labour has migrated to Kachin and northern Shan State to work on the large Chinese-backed plantations, including Chinese for plantations very close to the border. This scenario has prompted Kachin to argue that these land investments are causing social upheaval and have facilitated ‘Burmanisation’ and militarization of their ethnic territories. In some parts of Kachin State, such as Hpakant, non-Kachin migrant labourers outnumber locals, which some argue affected election outcomes in those areas.

Fig 6: Log, then build a dirt road, plant rubber seedlings, and don’t forget the fence and gate. This is rubber development in northern Burma.

However, the situation is quite different in the Wa region in north-eastern Shan State under the sole administration of the ceasefire group the United Wa State Party/Army (UWSP/A). Chinese business(wo)men seeking to obtain a rubber concession in Wa territory must go through Wa military authorities (the level of the authority dependent on the size of the company and concession desired) who then attempt to regulate and monitor the investments. The Wa authorities also manage labour demands for the rubber by relocating local populations to nearby sites.

The politics of rubber development in Wa territory underlines the dangerous mix of aggressive rubber promotion, close ties to Chinese authorities and finance, and food insecurity. Rubber replacing former swidden fields has exacerbated already a dire situation for the UWSP/A to feed their people and army, with one of Burma’s lowest crop yields and rice security. The Wa region is now exclusively reliant upon China for food imports to sustain the population, as they cannot import food from Burma ‘proper’ due to political and infrastructure reasons, as recently explained to me by one UN food security expert in Burma. The southern portion of Wa’s northern territory represents some of the only areas in which food production is possible for the UWSP/A (due to gentler slopes), which is the same territory the Burmese regime (State Peace and Development Council, or SPDC) now demands to be handed over to them after elections. The UWSP/A is now left between a rock and a hard place – China maintains complete leverage over them as the sole provider of needed food imports, the SPDC wants control over their food basket, and Chinese rubber plantations (which are mostly not yet being tapped) are eating away at their limited agricultural swidden fields. Wa authorities are left playing a waiting game after the elections: stalling negotiations with the SPDC until the rubber trees are able to be tapped so they can channel the latex profits into their continued struggle for political autonomy.

Fig 7: Rubber plantations in Wa territory near Panghsang, the Wa capital (TNI).

In northern Burma nearly all agricultural contracts with Chinese businessmen go through local and regional military authorities, whether the northern military commander, a ceasefire group such as UWSA or KIA, or a small insurgent group such as Mang Bang in northwestern Shan State. The military officials guarantee the land for Chinese investors through force, displacing peasants from their upland swidden fields. Some of these farmers are the very peasants who recently transitioned to a non-poppy livelihood as forced by the KIO, UWSP and other international actors, such as UNODC and USDEA. Legal justification by the Burmese military state is available through their 1991 ‘Wastelands Law’, which offers ‘wastelands’ and ‘fallow lands’ to private enterprises for large-scale agricultural development, at little to no cost.

China’s renewed interest in land development in the Mekong region, and the capital that facilitates this, is matched by the recipient country’s desire for large inputs of foreign investment needed to remake landscapes as governable, modern state spaces. The overall result of this contemporary assemblage of state laws and policies, military/state force, and transnational finance capital is to radically transform not only the biophysical landscape, but also the ways in which the resources and populations contained within become governed.

The recent elections play a central role in this convergence with key Burmese business and military elite winning seats in areas targeted for further land investment, conveniently covered up in the country’s roadmap to democracy. For example, Htay Myint of Yuzana Company won the Lower House seat as a USDP representative (the ‘government’s party’) for Myeik township in Tanintharyi Division, where he has established a monopoly on the country’s oil palm sector (on refining and import/export quotas with around 150,000 acres in oil palm concessions). Maj. Gen. Ohn Myint is his friend and apparent business partner, who is the former regional military commander of Tanintharyi Division (when Htay Myint started his oil palm business there) and later of Kachin State (when Htay Myint was awarded a 200,000 acre cassava concession in Hugawng Valley). Ohn Myint recently also won the Hpakant Township, Kachin State, Lower House seat for USDP. He ran against Bawk Ja, the famed activist farmer who has taken Htay Myint’s Yuzana Company to court in a historical battle of displaced farmers fighting for their land lost to Yuzana’s massive agricultural concession in Hugawng Valley’s Tiger Reserve (see report here).

More research is needed, however, on how these new forms of land investment effect territorial sovereignty, military-state building and ethnic conflict. For example, to what degree are the land concessions contributing to the entrenchment of the military-state? Are the concessions bringing the Chinese state in or the Lao or Burmese (military-) state in? Although this is very difficult to test due to political and methodological challenges, it seems that land investments are producing a confusing mixture of hybrid state – and state-like – authority in the uplands.

Swidden fields become private concessions awarded by military officials through state agencies, new battalions and military-guarded roads are constructed, upland ethnic populations are relocated along valley roadsides, and the forestry and agriculture ministries manage the landscapes according to their respective land categories. Military-private partnerships are the new apparatus governing resources and peoples in Burma on behalf of a minimally-functioning government. The military gains control over new territories through policing land concessions and establishing nearby battalions, while the land becomes administered by state agencies instead of through customary institutions. Thus Chinese land concessions in northern Burma directly participate in military-state formation.

And what does all this mean for upland ethnic populations’ lives and livelihoods? While TNI research has clearly shown that ethnic farmers in northern Burma are not accruing any benefits at all, upland farmers in Laos are able to direct some financial and other benefits into their villages, although perhaps less so with the arrival of bilateral, large-scale Chinese agricultural investments.

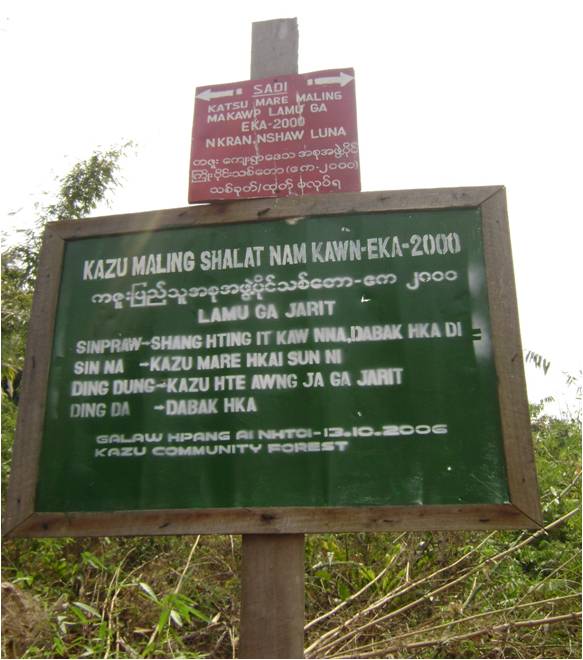

Fig 8: Officially demarcated community forest sign in Kachin State (Anonymous Kachin researcher).

Farmers are not just apathetically watching their farmlands stolen, however. Villagers in northern Burma are now busy trying to officially convert their upland swidden fields into state-sanctioned community forests and permanent agricultural household (titled and terraced) plots as an explicit mechanism to block land confiscation by agribusiness companies, with some success.

Fig 9: Official community hill forest in the background that villagers were able to keep away from a Chinese company who has leased the villager paddy land for a future rubber plantation. This is a celebrated case story in Kachin State (Anonymous Kachin researcher).

This puts researchers and NGOs into a difficult theoretical and practical dilemma: resistance strategies to protect and support communities from large-scale land investments – formalizing land titles recognized by the state – seem to converge with neoliberal mechanisms to promote capitalist markets and transnational investment, a la Joseph Stiglitz.[iii]

Kevin Woods is currently a doctoral student at UC-Berkeley in the Environmental Science, Policy and Management Department (ESPM), Society and Environment Division. He has been working in montane mainland Southeast Asia for over ten years as a political ecologist studying upland resource management and conflict/war. His current research project examines the emerging role of agribusiness in Burma. He can be contacted at [email protected]

[i] TNI. 2010. Alternative Development or Business as Usual? China’s Opium Substitution Policy in Burma and Laos. Drug Policy Briefing No. 33, November.

[ii] Weiyi Shi. 2008. Rubber Boom in Luang Namtha: A Transnational Perspective, GTZ, February. For other reports on rubber development in northern Laos, see Alton, C., Blum, D., and S. Sananikone. 2005. Para Rubber Cultivation in Northern Laos:Constraints and Chances, Study for Lao-German Program Rural Development in Mountainous Areas of Northern Lao PDR, Vientiane. Manivong, V. and R. Cramb, 2006. Economics of Smallholder Rubber Production in Northern Laos, 51st Annual Conference of Australian Agriculture and Resource Economics Society, Queenstown. Fujita, Y., et al. 2007. Dynamic land use change in Sing District, Luang Namtha Province, Lao PDR. International Program for Research on the Interactions between Population, Development, and the Environment (PRIPODE), Faculty of Forestry, National University of Laos. Sithong Thongmanivong et al, 2010. Concession or Cooperation? Impacts of recent rubber investment on land tenure and livelihoods: A case study from Oudomxai Province, Lao PDR. National University of Laos, Rights and Resources Initiative and the Regional Community Forestry Training Center for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok.

[iii] Tania Li explores this very issue in a recent article that challenges academics and practitioners alike to critically reflect on our role in keeping peasants buffered from the market as development intervention. ‘Indigeneity, Capitalism, and the Management of Dispossession.’ Current Anthropology, Vol. 51, No. 3 (June 2010), pp. 385-414.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss