Note: This article consolidates my preliminary observations based on one book. Due to time constraints and lack of sources, I am unable to gather wider knowledge about kite flying activities. I would be happy to hear corrections and comments from historians, as well as from those who know more about kite flying. Thai names and translations are intended to be easy to read. All errors and mistakes are mine alone.

Recently I came across an interesting manual in the Australian National University library: tamnan wow panan tamra phook wow witee chuck wow lae karn to-su kan nai arkard [A history of kite fighting, the manual on how to make, fly, and fight kites], which I would like to share with the readers of New Mandala.

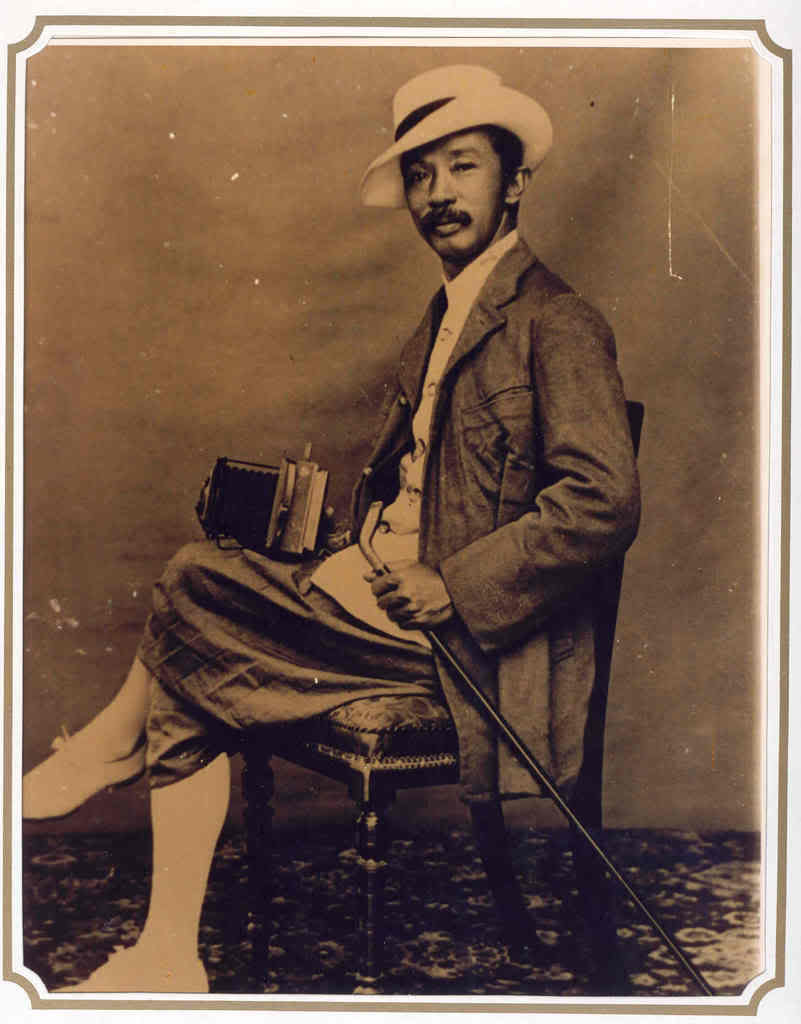

Front cover of the original version (1921)

According to the preface, the book is a reprint version for the first Thai Kite Fair held in 1983 by Boon Rawd Brewery Co. Ltd., which was headed by Prachuab Pirompakdi at the time.

The author of the book (and the father of Prachuab), Phraya Pirom Pakdi (1) (Boonrawd Setthabut, 1872-1950; Phraya Pirom hereafter), writes in the preface of the original version (1921) about his intention to write this manual (Phraya Pirom, khor kuad):

…at first I was thinking about writing from what I know [about kites] and publish it and circulate among our friends who love kite fighting, which is the Thai sport. But after I had a meeting with Prince Damrong Rachanuphab, he suggested that I should do further research and he would also write me a preface for the book…

…Eventually I decided to publish 1000 copies. 700 copies will be on sale and the money will go to the Department of Aircraft, 200 will be given to the Wachirayan Library, and 100 will be circulated among friends…

The interesting thing is how the idea to write this book was encouraged by Prince Damrong (then headed the Wachirayan Library), who wrote the preface (Phraya Pirom, kor kai, khor khai):

…I agree with Phraya Pirom’s project to write this book. This is because I see that kite flying is a Thai sport that is very popular…

…this book will be useful in two ways; first, it will educate the audience about the history of kite fighting [in Thailand] and secondly, it will be the reference book for kite fighting, which is a Thai sport…

The statement reflects how kite flying was famous enough to have someone writing a manual about it, and how it was supported strongly as a “Thai” sport by members of the Bangkok elite at the time.

Phraya Pirom Pakdi (1872-1950) Prince Damrong Rachanuphab (1862-1943)

A history of kite flying in Siam and elsewhere

The book begins with an introduction about how kite flying became a popular sport in ancient Siam. Phraya Pirom refers to information he received from Phraya Boran Ratchatanin, the viceroy in Ayutthaya province, that kite flying was recorded in the Royal Chronicle of the North (2), stating that Phra Ruang of Sukhotai (c.1238-1438) was a kite enthusiast (Phraya Pirom, 16). In Thao See Chulalak record, kite flying was a part of the state ceremony (Phraya Pirom, 16).

In the kingdom of Ayutthaya (c.1350-1767), King Ramathibodee I issued a palace decree to forbid flying kites within the vicinity of the palace. This shows how kite flying was popular among the Siamese, at least for those who lived within or around the palace. Also, in La Loubère’s record (1688) he observed how the Siamese under King Narai enjoyed flying kites (Phraya Pirom, 16-17).

Kite flying also played a part in warfare. When Phra Petracha invaded Ratchsima in 1690 he attached clay pots filled with oil to each kite and flew them over Ratchsima’s city wall. Then he lit the wires attached to the pots, so they burnt and a rain of fire was dropped into the city, which made Ayutthaya secure Ratchsima as its dependency (Phraya Pirom, 17). Further as the dominant style of Thai historiography goes, the early Bangkok era (1782-present) saw King Rama II (r.1809-1824) become a fan of kite flying (Phraya Pirom, 18).

Phraya Pirom also added the history of kite flying abroad. He refers to how kite flying was also visible in Europe and America (he mentions Benjamin Franklin’s famous experiment). There was also kite flying traditions in ancient Japan, China, and India. He mentions in passing that the Yuan and Khmer did not have kite fighting. They only imitated kite flying from China (Phraya Pirom, 10-3).

Phraya Pirom’s attempt to portray the long history of kite flying as far back as the birth of the ‘Siamese nation’ attracts my attention. In a sense, this book shows the perception of the Thai elite during the early twentieth century. On the one hand it shows how ‘writing history’ was in demand especially after Prince Damrong began to devote most of his time to taking care of Thai history in 1915, when he officially headed the National Library. On the other hand, by stressing how kite flying belongs to the ‘Thai’, the elite also emphasized ‘Thai nationalism’ spearheaded by King Vajiravudh (r.1910-1925) (3). Phraya Pirom wrote that the “kite fighting that we are adopting today is well understood as being unique. There is no other country that has such a sport. This shows how our kite fighting is more innovative and better than that in foreign countries” (Phraya Pirom, 10). Thai historiography, which was (and is) much dominated by Prince Damrong’s school, is full of the history of activities engaged in by kings and nobles. Kite flying, therefore, fits into the need of the Thai elite to write their own history (Breazeale, 25-49, 35) (4). Prince Damrong saw it as important enough for him to write the preface for this manual.

The perception of the Thai elite is also reflected in the way a limited number of nations were mentioned in the text, namely Europe, America, Japan, China, and India. These countries, at least in Phraya Pirom’s eyes, were ‘major powers’. In fact, Phraya Pirom’s account of how Siam was the only country with a kite fighting tradition might be wrong. Kite fighting in Korea can be traced back to the year 637, during the first year of Queen Chindok of Silla. Kite fighting is also prominent in Korean history. In Brazil, the popular piao fighting tradition is believed to have a long history. Malaysia’s waus also has a long history (5).

Korean kites

Brazillian ‘Piao’ Malay ‘Waus’

The point is not whether Phraya Pirom was right or wrong. But it offers guidance on how the countries mentioned by him were central to the Thai elite’s global perspective at the time.

Kite flying in modern Siam

Phraya Pirom refers to his childhood, when he saw his father Phra Pirom Pakdi (Chom Setthabut) as a kite enthusiast. His father enjoyed fighting kites, which took place at Samyod Gate and then moved to Siew Bridge next to Baworn Palace (the area where the National Museum and the National Theatre are located today).

Sampeng Market. Samyod Gate is in the background. This photo was taken around the 1890s

When Phraya Pirom was 10 years old, he witnessed kite fighting at the field at Wat Khok. The competition took place there until 1889, when King Chulalongkorn initiated a project to make Thepsirin Road because Bangkok was getting more crowded and there were increasing numbers of foreigners’ residences in the area (Phraya Pirom, 20-1).

Phraya Pirom provides some names of people who participated in these kite fighting competitions. They included Phraya Anuchitcharnchai, Phraya Thammasatnatpranai, Phraya Pururatrangsan, Phra Naisamerchai, Phraya Rachanupraphan, Luang Lekhawicharn, Luang Sarachak, Luang Prab and Phraya Thep-orachun (Phraya Pirom, 21).

When the kite competition at Wat Khok stopped, kite fans gathered outside Sra Prathum Palace. The competition was under the patronage of Somdet Phra Baromawongter Kormluang Sawaswattanawisit, who himself enjoyed watching kite fighting. Phraya Pirom states that there were not many participants at this field due to its more distant location and there was not any public transport (Phraya Pirom, 24-5). In other words, this field was exclusively for those who owned cars and had connections with the owner of the property.

Kite flying also carries with it a signifier of elite practice, when Phraya Pirom illustrates how the field at Wat Don was another favourite place for kite fighting (Phraya Pirom, 25):

…at first it was a very famous place because it suited kite flying. But after a while, it began to be filled with drunkards who every night got drunk all over the place. It was such an unpleasant scene and made less people participate in, and kite flying eventually stopped…

Kite flying at Wat Don made me think about the areas where the lower and the upper classes came to interact. At the turn of the century, Bangkok was undergoing urbanization. The number of public spaces increased and this resulted in more interaction between different classes. It was not only the field at Wat Don where elite resentment at contact with the lower classes was evident, but also in other public spaces. Scot Barmé illustrates how this sentiment was evident in cinema-going where the upper class felt that the lower class spoiled their good movie-going experience (Barmé, 70-3).

The urbanization of Bangkok also caused kite fighting to be moved to various places such as Hua Lumphong, Yod Se Bridge, Suan Anan and Bang Khunphrom but eventually it had to stop because people began to settle around those areas and kite flying could cause damages to public property (Phraya Pirom, 25-6).

The golden time of kite flying in Bangkok came in 1905, when King Chulalongkorn passed by Sanam Luang (which had become the main place for kite fighting a few years earlier) and wanted to know more about kite fighting. He ordered kite fighting at his residence, Suan Dusit Palace (the area which is at Samosorn Suapa and around Ananta Samakom Throne Hall today) and watched it enthusiastically every afternoon. At the end of each competition, he rewarded the winner with a garland by his own hand. How much King Chulalongkorn enjoyed watching kite fighting was demonstrated when he asked the participants to organize an event annually, and offered the winner the Royal Trophy (and also the Queen’s Trophy). He even had Prince Damrong set rules for the kite fighting competition at Suan Dusit and distributed them among participants in 1907 (Phraya Pirom, 37, 47). It was during this time that kite fighting at Suan Dusit Palace was more crowded than ever (Phraya Pirom, 33-4).

Kite competition at Sanam Luang during King Chulalongkorn’s reign

King Chulalongkorn chaired the crowded kite competition

Some of the elite also participated in kite fighting themselves, such as Krom Luang Ratchburi Direkrit and Krom Luang Chumponket Udomsak (both sons of King Chulalongkorn). At the end of the day, they organized dinner and gave Rothschild cigarettes to the participants (Phraya Pirom, 34).

After kite fighting became King Chulalongkorn’s favourite, Sanam Luang became crowded with people, both amateurs and experts. Kite flying was somewhat ‘in’ for Bangkok dwellers at the time. It was the upper class who first enjoyed flying kites and later on the lower class followed.

Compared to today, kite watching was the Academy Fantasia (AF) concert for Bangkok dwellers about a century ago

The written rules on kite fighting which were approved by King Chulalongkorn in 1907

Epilogue

It appears that kite fighting declined after the end of King Chulalongkorn’s reign. Although it did not stop completely, kite fighting was not as enjoyable as it once was, at least for Phraya Pirom.

In his manual, he also adds details on how to make a kite from scratch, how to fly and fight the kite, and so on. As it is called ‘art’ (sinlapa) in this manual, kite flying was definitely an activity very much enjoyed by the Thai elite at the turn of the twentieth century.

As a person who grew up in Bangkok, I used to enjoy chuck wow at Sanam Luang. I can still remember how to maintain a kite and how to make the kite rise higher in the sky. It is only in the past decade that I stopped going there to fly kites because Sanam Luang has changed so much. The green field has almost totally become a cement pavement and a parking lot. It worries me that the next generation will eventually forget about this activity, when no one seems to care about it any more today.

Kite flying has become an image for a tourist poster today

References

Phraya Pirom Pakdi (1921) Tamnan wow panan tamra phook wow witee chuck wow lae karn to-su kan nai arkard (Bangkok: Sophon).

Breazeale, Kennon (1971) A transition in historical writing: the works of Prince Damrong Rachanuphap. Journal of the Siam Society 59(2), pp.25-50.

Barmé, Scot (2002) Woman, Man, Bangkok: Love, Sex, and Popular culture in Thailand (Bangkok: Silkworm).

Notes

(1) Phraya Pirom was the founder of the Kite Association of Thailand. He was also the founder of Singha Beer that we enjoy today. His life is interesting in a sense that he was the first to move into the beer business and won state support for capital investment in the 1930s, which was before the law on state’s promotion of investment was written under Sarit Thanarat’s regime in 1958 (under the United States’ supervision). This topic awaits further research.

(2) The Chronicle states: “…р╣Бр╕ер╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╕гр╣Ир╕зр╕Зр╕Вр╕Ур╕░р╕Щр╕▒р╣Йр╕Щр╕Др╕░р╕Щр╕нр╕Зр╕Щр╕▒р╕Б р╕бр╕▒р╕Бр╣Ар╕ер╣Ир╕Щр╣Ар╕Ър╕╡р╣Йр╕вр╣Бр╕ер╣Ар╕ер╣Ир╕Щр╕зр╣Ир╕▓р╕з…” Also, “…р╕зр╕▒р╕Щр╕лр╕Щр╕╢р╣Ир╕Зр╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕нр╕Зр╕Др╣Мр╕Чр╕гр╕Зр╕зр╣Ир╕▓р╕зр╕Вр╕▓р╕Фр╕ер╕нр╕вр╣Др╕Ыр╕Цр╕╢р╕Зр╣Ар╕бр╕╖р╕нр╕Зр╕Хр╕нр╕Зр╕нр╕╣ р╣Бр╕ер╕░р╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╕Хр╕нр╕Зр╕нр╕╣р╕Щр╕▒р╣Йр╕Щр╣Ар╕Ыр╣Зр╕Щр╕Вр╣Йр╕▓р╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╕гр╣Ир╕зр╕З р╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╕гр╣Ир╕зр╕Зр╕Хр╕▓р╕бр╣Др╕Ыр╕Цр╕╢р╕Зр╣Ар╕бр╕╖р╕нр╕Зр╕Хр╕нр╕Зр╕нр╕╣ р╣Бр╕ер╕░р╣Др╕Фр╣Йр╣Ар╕кр╕╡р╕вр╕Бр╕▒р╕Ър╕Шр╕┤р╕Фр╕▓р╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╕Хр╕нр╕Зр╕нр╕╣ р╣Ар╕бр╕╖р╣Ир╕нр╣Др╕Фр╣Йр╕зр╣Ир╕▓р╕зр╣Бр╕ер╣Йр╕зр╕Бр╣Зр╣Ар╕кр╕Фр╣Зр╕Ир╕Бр╕ер╕▒р╕Ъ р╕ер╕╣р╕Бр╕кр╕▓р╕зр╕Ир╕╢р╕Зр╕Ър╕нр╕Бр╣Бр╕Бр╣Ир╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╕Хр╕нр╕Зр╕нр╕╣ р╣Ж р╕Ир╕╢р╕Зр╣Гр╕лр╣Йр╣Др╕Ыр╕Хр╕▓р╕бр╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╕гр╣Ир╕зр╕Зр╕Др╕╖р╕Щр╕бр╕▓ р╕Др╕гр╕▒р╣Йр╕Щр╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╕гр╣Ир╕зр╕Зр╕бр╕▓р╕Цр╕╢р╕Зр╣Ар╕бр╕╖р╕нр╕Зр╕кр╕▒р╕Кр╕Щр╕▓р╣Др╕ер╕вр╣Бр╕ер╣Йр╕зр╕Хр╕гр╕▒р╕кр╕кр╕▒р╣Ир╕Зр╣Ар╕Ир╣Йр╕▓р╕Юр╕кр╕╕р╕Ир╕┤р╕Бр╕╕р╕бр╕▓р╕гр╕зр╣Ир╕▓р╕Ир╕░р╣Др╕Ыр╕нр╕▓р╕Ър╕Щр╣Йр╕│ р╕Цр╣Йр╕▓р╣Др╕бр╣Ир╣Ар╕лр╣Зр╕Щр╕Бр╕ер╕▒р╕Ър╕бр╕▓р╕Бр╣Зр╕Вр╕нр╣Гр╕лр╣Йр╣Ар╕Ыр╣Зр╕Щр╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕вр╕▓р╣Бр╕Чр╕Щр╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕нр╕Зр╕Др╣М р╕Ир╕▓р╕Бр╕Щр╕▒р╣Йр╕Щр╕Юр╕гр╕░р╕нр╕Зр╕Др╣Мр╕Бр╣Зр╣Др╕Ыр╕нр╕▓р╕Ър╕Щр╣Йр╕│р╕Чр╕╡р╣Ир╕Бр╕ер╕▓р╕З р╣Бр╕Бр╣Ир╕Зр╣Ар╕бр╕╖р╕нр╕З р╣Бр╕ер╣Йр╕зр╕нр╕▒р╕Щр╕Хр╕гр╕Шр╕▓р╕Щр╕лр╕▓р╕вр╣Др╕Ы…”

(3) For an important account to understand King Vajiravudh’s ‘official nationalism’, see Kullada Kesboonchoo, Official Nationalism under King Chulalongkorn, 1987, Paper presented at the International Conference on Thai Studies, Canberra, Australia [Those who are interested can find this paper at TIC, Central Library, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok]

(4) Breazeale suggests that “By 1932 with the end of Damrong’s tenure in the library, Thai historical writing had begun to emerge from an undistinguished past and had given some definite shape to the general notions about Thai history.”

(5) This is not to mention how the Afghans also love kite fighting. Remember the movie the Kite Runner (2007)?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss