Since the International Conference on Thai Studies, I have received a number of requests for the paper I presented on sufficiency economy. The paper was not included on the conference CD because I did not have time to submit it. So, here is the full text of my presentation. This is an edited version of a longer and much more detailed paper (which I am still writing). Regular readers of New Mandala will recognise much that is familiar!

A good place to start is a fairy story that has been produced in Thailand. The lavishly illustrated story recounts the adventures of a little kingdom and its good king, who triumphs over a series of dark forces.

One of the king’s triumphs occurs during his many travels around the kingdom.

In a far off place, the king came across a village that had almost no one living there. “Where has everyone gone” the king asked the small group of remaining villagers.

The villagers answered their king: “A demon of the dark called “GREED” came and visited and asked the people to leave the village. Most of the villagers abandoned the village and went to live in the “City of Extravagance.”

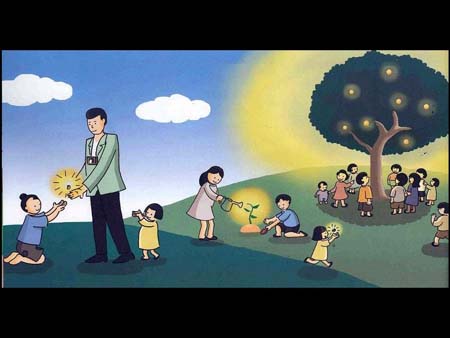

The king thought for a moment and then gave the villagers a radiant seed. The villagers took the seed and planted it and it grew into the “radiant tree” that grew large branches and spread its radiance in all directions.

The king told the villagers that the radiant tree is called “SUFFICIENCY.” The radiance of the tree shone to far off places, as far as the City of Extravagance. And many of those who saw it travelled back to return to their village.

Since the 2006 coup Thailand has embarked on an unprecedented spate of enthusiasm for the royal theory commonly referred to as sufficiency economy. In order to draw a clear contrast with the so-called populist policies of the overthrown Thaksin government, the coup makers have devoted considerable attention to presenting their policies within a yellow package of royalist sufficiency. Of course, much of this is rhetorical. It is hard to see how a 60 percent increase in the military budget could be consistent with the sufficiency economy prescription of reasonableness, moderation and efficiency.

Nevertheless, sufficiency economy has become an ideological tool that seeks to moderate rising rural expectations for economic and political inclusion. Whatever sufficiency economy thinkers may have to say about urban consumers or businessmen, it is towards rising rural expectations for economic and political inclusion that the sufficiency economy urgings of moderation are most clearly directed. This is ideologically linked to the active delegitimisation of rural voter’s electoral wishes in the post coup environment. Not only are rural people to be shielded (or excluded) from full and active participation in the national economy but their full and active participation in electoral democracy is delegitimised and the power of their elected representatives constrained.

At the heart of sufficiency economy’s approach to rural Thailand is its three stage process of human development. This staged process of development builds on a foundation of self reliant agriculture. The first stage of human development involves the famous “model farm,” a much cited example of royal genius. In the model farm, land is allocated (in thirds) between fish ponds, rice cultivation and crops/fruit.

Of course, it would be foolhardy to take model farm too seriously but the emphasis on local agricultural production as a basis for household sufficiency is clear.

But, the sufficiency economy advocates protest, this is not about a rejection of the market altogether. In the king’s vision “self-reliance did not mean isolation. The model farm was expected to create a surplus beyond household consumption, and this surplus could be exchanged on the local market.” Stage 2 in the sufficiency economy model of development extends self reliance to the community level with local exchange of household surpluses to meet local needs.

And, in turn, Stage 3 involves a higher level of external exchange to sell excess production and to obtain technology and resources.

It should be clear, then, that sufficiency economy is not about economic isolation. Stages 2 and 3 involve increasing levels of external exchange. But, and this is crucially important:

Before moving to another stage, there first had to be a firm foundation of self-reliance or else there was a strong chance of failure and loss of independence. The driving force for development had to come from within, based on accumulation of knowledge.

So, the sufficiency economy approach proposes a hierarchical model of rural economy in which livelihoods are based on a broad foundation of local agricultural sufficiency. On top of this foundation local and non-local exchange involves the circulation of surpluses produced within the subsistence-oriented base. Local subsistence needs, not regional, national or international market demand, are the key drivers of production. The exchange of surplus is primarily a fortuitous by-product of the abundance of locally-oriented production.

In this paper I argue that this sufficiency economy view seriously misrepresents the nature of rural livelihoods in contemporary Thailand. The view that agriculture can provide a “firm foundation of self reliance” is a highly selective and simplified interpretation of contemporary economic realities in rural Thailand. In fact, local agriculture frequently exists, and persists, on a foundation of external social and economic linkages. The notion that external linkages should only be developed once there is a foundation in local sufficiency is simply not consistent with the economically diversified livelihood strategies pursued by rural people in contemporary Thailand. It is an agrarian vision from the past.

I will demonstrate this, quite briefly, by examining the local economy in the village of Baan Tiam – a lowland northern Thai village located about one hours drive from Chiang Mai.

The first thing I want to examine is Baan Tiam’s demographic transformation.

Over the past 50 years there has been sustained population growth in Baan Tiam. The village has expanded well beyond the original cluster of early settlers.

This population growth has been associated with two key demographic processed. First, as in many other parts of rural Thailand, Baan Tiam has been a substantial exporter of population. Second, local population growth has been accompanied by an ongoing withdrawal from agricultural activity. This withdrawal has been driven both by agricultural resource constraints and expanding opportunities in other sectors.

These trends can be nicely illustrated in relation to the lineage of great-great-grandmother Pim, who was the mother of this woman. At present I have information on 87 of her descendants and their spouses. Of these almost exactly half are living outside the village and I have no doubt that there are considerably more, given that my genealogical information on these scattered descendants is much less complete.

Among those still living in Baan Tiam the relatively small number still working in agricultural is striking. Grandmother Pim has 20 descendants currently resident in Baan Tiam who are of active working age. Of these only about 10 are still active farmers. And the situation among Pim’s Baan Tiam descendants is fairly representative of the situation in the entire village.

In brief, an examination of Baan Tiam’s livelihood demography immediately raises important questions about the plausibility of an economic foundation in local sufficiency. There is no doubt that agriculture plays a very important role in Baan Tiam’s economy but rather than representing a foundation for local sufficiency it is itself underpinned by substantial out-migration and internal economic diversification. To put the matter bluntly: without these external livelihood options the internal competition for agricultural land in Baan Tiam would be extreme and large numbers of residents would be forced to adopt low yielding upland agriculture in the neighbouring national park in pursuit of the most basic subsistence livelihoods. The pressure on natural resources would be immense. If all of great-grandmother Pim’s descendants were to return to the village from the city of extravagance the royal tree of sufficiency would soon be cut down and sold to a furniture factory in Hang Dong.

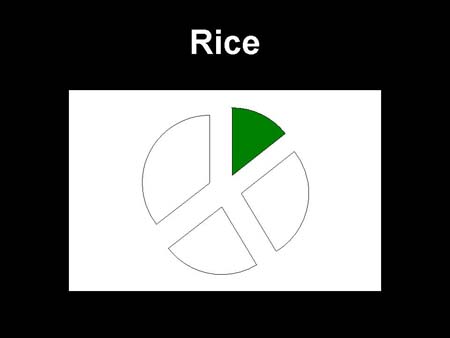

I will now move on to examine the main sectors of Baan Tiam’s economy. I will start with rice, and here I have provided a very rough indication of the size of the rice sector within the overall village economy.

In relation to rice I will make five quick points.

First, in a very broad sense Baan Tiam can be regarded as self sufficient when it comes to rice. My estimate of the rice subsistence requirement for the village as a whole is about 120 tonnes. Under good cultivation conditions the village produces about 140 tonnes of rice.

But this broad impression of rice sufficiency is rather misleading.

In fact only slightly over half of the village’s households are engaged in rice cultivation (66 out of 126). The most common reason for non-rice cultivation is that the households do not own any agricultural land. The primary way in which non rice producing households obtain rice is via purchase either within the village (from rice surplus households) or outside the village (from rice traders in the nearby district centre). Some households obtain rice as payment for wage labour. So, while in a very general sense Baan Tiam can be regarded as being rice sufficient, the ways in which people access rice varies significantly. Images of local sufficiency, even in the limited sectors of the economy where they may be applicable, conceal local inequalities in access to resources and production. The key point is that many rural people obtain their most basic subsistence goods via market transactions.

The next key point is that Baan Tiam’s broadly defined rice sufficiency is a result of considerable out-migration. If significantly more people had remained in the village there simply would not be enough locally produced rice for local consumption needs and dependence on external purchase would be substantially higher than it is now.

And rice sufficiency is a relatively recent phenomenon. Farmers report that rice yields have increased dramatically in recent years as a result of the introduction of improved varieties (especially Sanpatong 1). These varieties require relatively high inputs of fertiliser but the greatly increased returns easily justify the additional outlay. Of course, the sufficiency economy model of rural development does provide for the introduction of new technology in Stage 3 of its model. But according to sufficiency economy precepts this should follow on from a firm foundation in self reliance and local knowledge. In Baan Tiam, and many other parts of Thailand, improved rice yields are the result of ongoing external investment in variety improvement, irrigation infrastructure and agro-chemical input.

And finally, despite its cultural importance, rice is only one component of the contemporary household economy. And, in fact, it is a relatively modest component. By my rough estimates the cash value of rice production makes less than 10 percent of average household incomes in northern Thailand. Even among those deemed to be living in absolute poverty rice production may represent only 20 or 30 percent of total income.

I will now move on to cash crop production. In Baan Tiam some cash crops are grown in the wet season, along with rice, but cash crop production takes place mainly in the dry season in irrigated paddy fields. Here is a very quick view of cash crop production.

In relation to cash crops I have four key points.

First, cash crop cultivation represents a larger sector of the economy than rice cultivation. One indication of their importance is that the production of cash crops was nominated by 34 percent of households as their most important source of income.

Second, Baan Tiam has been a long term cultivator of garlic, but in recent years there have been problems with yield. These problems are locally perceived to be caused by climatic variation and declining soil fertility. The free trade agreement with China in 2003 also had a short term effect on garlic prices and combined with a Thaksin government adjustment scheme this encouraged some farmers to move out of garlic production.

So, farmers in Baan Tiam have faced many of the same environmental and economic anxieties that have contributed to the sufficiency economy philosophy. As at a national level, Baan Tiam’s farmers have had to deal with concerns about resource degradation, environmental change and external economic impacts. But their response has been quite different to that laid down by the sufficiency economy precepts. Rather than seek limit their engagement with external markets and focus on consolidating a subsistence oriented agricultural base, farmers have pursued new forms of engagement with agricultural commercialisation.

Largely in response to concerns about garlic production, Baan Tiam’s farmers have adopted a range of new cash crops. Most of the new cash crops are grown under contract farming arrangements. Farmers regularly state that they have become interested in contract farming because they do not have to invest their own capital (which is usually borrowed). There is a strong sense in Baan Tiam that the advent of contract farming has introduced a wider range of agricultural alternatives into the village and these alternatives have been enhanced by some degree of revival in the yields and price of garlic.

This is a system based on the active exploration of agricultural options introduced from outside the village. While many farmers ultimately adopt one of the major crops this adoption is accompanied by careful observation and vigorous discussion of the numerous experiments that are going on at the margin. The relatively small areas devoted to minor crops may not be significant in terms of the overall local economy but they are sites of experimentation where agricultural alternatives are actively tested and evaluated.

I will deal with the issue of agricultural wage labour very briefly. The key point is that about 30 percent of Baan Tiam’s households are heavily dependant on agricultural wage labour, primarily because they do not own any land. Most wage labour opportunities occur in the externally oriented cash cropping sector – opportunities for local income are much more limited in the subsistence oriented rice sector.

And I will also deal with non-agricultural enterprise briefly. This is an important and diverse sector of Baan Tiam’s economy. I estimate that it represents something between 30 and 40 percent of the village economy. Key areas of enterprise and employment include construction, local handicrafts and small scale industry, government employment, and shop-keeping.

A key point to underline here is that the government is a key source of direct employment and of finance for other economic activities that generate local employment. The Thaksin’s government’s stimulus of this sector was a key reason for its electoral popularity in Baan Tiam.

I will finish up by making three general points about sufficiency economy and its misrepresentation of rural livelihoods. And this image, from the Bangkok Post, of one of the queen’s sufficiency economy projects in southern Thailand is a useful backdrop for the discussion.

First, the image of rural economy which underlies the sufficiency economy philosophy is not one that would stand up to any concerted ethnographic scrutiny in rural Thailand. It is an image in which external economic connections are, at best, peripheral and at worst highly disruptive. It is an image of rural livelihood in which subsistence oriented agriculture is seen as potentially providing a firm foundation for household livelihood and in which local subsistence needs are, or should be, the primary driver of economic activity.

In this paper I have sought to paint a rather different picture of rural economy. The data from Baan Tiam indicate that subsistence-oriented agriculture is just one component of a diverse and multifaceted economy. And it is a relatively small component.

My second key point is that the sufficiency economy prescriptions for rural development are inappropriate and disempowering. Perhaps the best outcome is that sufficiency economy will largely be ignored except as a promotional strategy for rural development programs. In the recent election Matchimathipatai’s sufficiency economy policy for 9 million fish ponds, based on the king’s vision of the model farm, didn’t seem to capture much electoral interest. They won seven out of 480 seats.

But the possibility that sufficiency economy principles may shape future rural development policy cannot be too readily dismissed, especially given the current force of royalist thinking. What is of most concern is the notion that local subsistence-oriented agriculture can act as a foundation for rural livelihoods and that this foundation should be firmly established before moving on to the later stages of development (local exchange and then limited external exchange). In relation to Baan Tiam I have already noted the very limited sense in which the subsistence agricultural sector could be seen as providing some basis for local sufficiency in rice. Making this quite modest part of the local economy a primary focus for rural development would be to condemn many rural households to a sector of the economy in which the potential for livelihood transformation is very constrained. A more realistic development standpoint would be too see the foundation for local livelihood as lying in a diverse and spatially dispersed package of agricultural and non-agricultural pursuits. Local economic resilience lies in diversity, not in a narrowing of focus to subsistence production and locally oriented exchange. Strengthening this diverse economic foundation involves a multi-faceted package of agricultural extension, enterprise development, infrastructure investment and, probably most importantly, high quality primary and secondary education. Of course, there is considerable potential for improving agricultural productivity and in enhancing subsistence security (especially for these most vulnerable farmers who cultivate subsistence crops on marginal lands). But enhancing local livelihoods will necessarily involve both supporting the production of higher value commercial crops and supporting the ongoing movement of household labour and resources into non-agricultural pursuits.

But perhaps the current preoccupation with sufficiency economy does not really reflect a concern with rural development at all. It is important to remember that one of the key ideological projects of the regime in post-coup Thailand has been to argue that the Thaksin government’s electoral mandate was illegitimate because it had been “bought” from an unsophisticated and easily manipulated electorate. The military and judicial overthrow of an elected government is justified on the basis that the Thai electorate, and especially the rural electorate, is in no position to make rational political decisions. Rural voters, we are consistently told, are vulnerable to the lure of vote buying and the political pressures of local strongmen. What is required is a political system in which electoral power is tempered by the guiding hand of the good men in the judiciary and the bureaucracy.

The sufficiency economy philosophy serves this ideological project very well. Its clear message is that the appropriate role for the rural population is in localised and modest pursuits. Matters of regional and national economy are for others to take care of. Underlying the sufficiency economy approach is the message that when rural people become involved in these broader economic pursuits they readily breach the moral regulations of reasonableness, moderation and immunity. Their journeys to the city are not attempts to improve their livelihoods but morally dubious pursuits of extravagance. In the same way votes cast for Thaksin do not reflect local political judgement but are the readily mobilised results of financial inducement. In this elite vision of electoral participation the problem lies in money politics – the demon of greed. The solution lies in the royally bestowed tree of local sufficiency.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss