The former general juggled the interests of reformers and hardliners during a turbulent time for Indonesia. But this important legacy is being overlooked, writes Terry Russell.

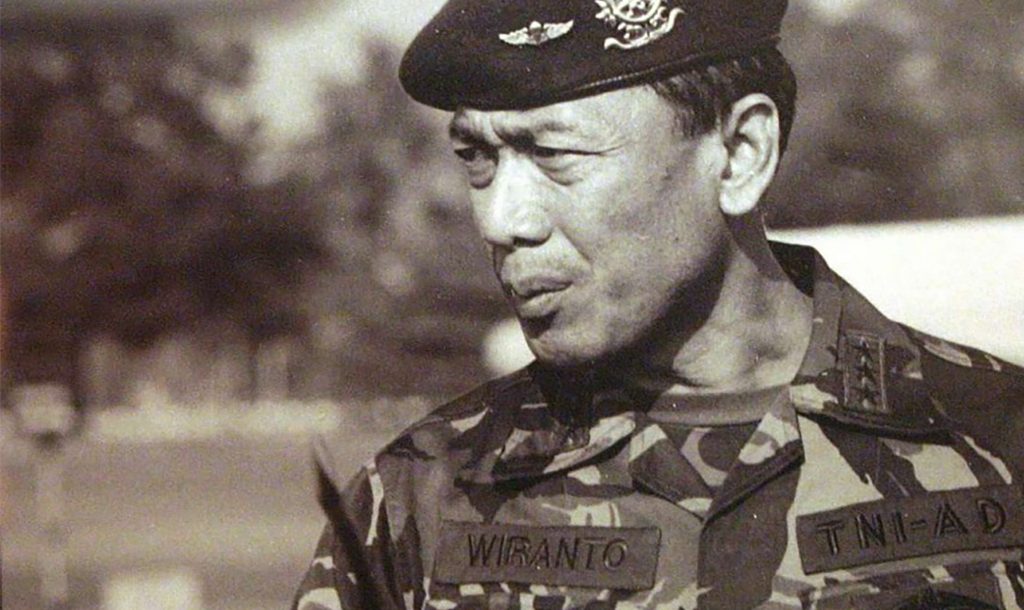

Wiranto, the man at the helm of the Indonesian military in the troubled years of 1998-2000, was inaugurated on 27 July 2016 as Indonesia’s new Chief Security Minister.

Some people have opposed this appointment, arguing that Wiranto planned or at least allowed horrific human rights abuses in 1998-2000. Certainly some horrific crimes against civilians occurred under Wiranto’s watch. But could he also be viewed as a political moderate who helped steer Indonesia through a difficult period as the Asian Financial Crisis threatened to tear the nation apart?

In 1998 I was living in Jakarta during the riots of May and the mass protests of November. That year, the value of the Indonesian rupiah had collapsed to 17,000 rupiah per US dollar, compared to just 2,400 rupiah per dollar in June 1997. Calls for East Timorese, Acehnese and West Papuan independence were becoming louder. Ethnic conflict was breaking out in many parts of Indonesia.

Rumours of high-level political rifts and impending coups circulated daily. Religious rifts were emerging even in the capital city and the word ‘balkanisasi’ (balkanisation) was part of the Indonesian lexicon. All of Wiranto’s actions, or inaction, at that time needs to be viewed within the context of a nation that was close to disintegration.

The biggest crime, though not the only crime, of which Wiranto is accused relates to the devastation wrought by the Indonesian military in East Timor in 1999. From January-September 1999, at least 1,200 civilians were murdered in East Timor by Indonesian security forces or their proxies and many thousands more had their homes looted and burnt.

The Indonesian government-sanctioned commission of inquiry into human rights abuses in East Timor (KPP HAM) concluded, “Armed Forces General Wiranto as Armed Forces Commander is the party that must be asked to bear responsibility.” Similarly, three years later UN investigators filed an indictment on behalf of Timor-Leste, but noted:

“Wiranto is the only man in this indictment against whom we don’t have evidence of personal participation, by which I mean we don’t have evidence of the things he said or orders he gave, which directly led to the establishment of militias. But throughout the whole period, he had command authority.”

Both inquiries assumed that a normal military chain of command was functioning in Indonesia in 1999.

But a deeper analysis of context raises questions about how much Wiranto was in control of his security forces in 1999 and whether he may have been forced to compromise with Suharto-era hardliners in order to hold Indonesia’s military together.

In 1999, Wiranto was a man under siege. Serving concurrently as Defence Minister and Chief of the Armed Forces, he was the man leading serious post-Suharto reforms in the military. In November 1998, he had reduced the military’s automatic allocation of 75 seats in the nation’s 500-seat parliament to just 38.

In April 1999, he had formally separated the military from the police force, as part of a move to help the military focus on external rather than domestic threats. Around the same time, he ordered that 3,000 military personnel who had been seconded to local government administration positions during the Suharto era either resign from the military or resign from their local government administration positions. In addition to these reforms, he was being asked to provide security for a referendum that might separate East Timor from Indonesia.

He turned 52 in 1999, so many generals that were technically under his command were significantly older than him. Their feelings were expressed publicly by retired Colonel Gatot Purwanto in early 1999, criticising Wiranto as, “A man who has spent too much time carrying other people’s briefcases and who knows nothing about the sufferings of the ordinary soldier.” As Wiranto pushed through reforms, there is no doubt he would have been generating angst amongst some hardliners.

But at the same time, he also faced another source of resistance from within the military – elements within the Special Forces (Kopassus). In June 1998, he had overseen the demotion of former Kopassus commander Prabowo Subianto, who also happened to be Suharto’s son-in-law. Wiranto had then overseen a probe into Prabowo’s role in the disappearance of human rights activists in May 1998 – a probe that led to Prabowo’s complete ousting from the military in August 1998. In April 1999, the same probe sentenced 11 members of Kopassus to jail terms of up to 22 months.

Wiranto’s own military background was in the infantry, so he did not have strong connections into Kopassus. Kopassus, which at that time was also implicated in fomenting the riots of May 1998, was a particularly unruly element of Indonesia’s military. Wiranto had Prabowo’s ally, Major General Muchdi Purwoprandjono, replaced as chief of Kopassus, however throughout 1999, Wiranto would have remained wary of a backlash from elements from within Kopassus.

There were still more divisions.

Ever since the 1980s, there had been growing factionalism within Indonesia’s military. Officers were vying for promotion by aligning themselves with an Islamist faction, known as ABRI Hijau, or a secular faction, known as ABRI Merah-putih. Prabowo had been a key member of the Islamist faction and Wiranto had been steadily gravitating towards the secular faction.

It is said that when Wiranto initially proposed a Christian general, Luhut Panjaitan, to become the new head of Kopassus in mid-1998, the ABRI Hijau faction was strong enough to block this choice. By January 1999, Wiranto had eased ABRI Hijau loyalists such as Fachrul Razi and Zacky Anwar out of key positions, replacing them with ABRI Merah-putih loyalists. Wiranto had chosen a path of demoting some opponents and compromising with others instead of a violent purge of the military.

The gulf that opened between these factions in 1998-1999 was real. So real that it remained a gulf right up to the presidential election of 2014, where the Islamist faction, including retired generals Kivlan Zen and Sudrajat, lined up behind Prabowo. The secular faction, including retired generals Wiranto, Luhut Panjaitan and Hendropriyono, lined up behind Joko Widodo (Jokowi). Throughout 1999, Wiranto would have been wary of a backlash from the Islamist faction. To deem Wiranto in full control of Indonesia’s armed forces in 1999 is to misread the context.

East Timor was not the only conflict zone in Indonesia that Wiranto was dealing with in 1999. Communal violence had broken out in Kupang, West Timor in November 1998. Further ethnic violence had broken out in Poso, Central Sulawesi in December 1998, and in Sambas, West Kalimantan in January 1999. These all fed upon ethnic rivalries to control local government positions or local economic resources in the wake of the power vacuum that followed Suharto’s resignation.

Most of these were quickly subdued, but throughout 1999 Indonesia’s military would have remained on alert. In August 1999, as Indonesia’s military prepared to ‘safeguard’ the referendum in East Timor, it was also preparing 7,000 security forces personnel to launch Operation Sadar Rencong II against separatists in Aceh province, dealing with new communal clashes on Batam Island and dealing with ongoing communal violence in Maluku Province. With so many flashpoints, Wiranto may not have been heavily involved in the planning around East Timor.

Evidence points to General Feisal Tanjung and Major General Zacky Anwar Makarim as the architects of the human rights abuses in East Timor in 1999. Wiranto, willingly or unwillingly, played more of an accomplice role. General Feisal Tanjung, who was serving as Coordinating Minister for Politics and Security in 1999, had been the Armed Forces Chief before Wiranto so he was very well connected. He also happened to be a key member of ABRI Hijau and a former Kopassus commander. To help prevent a backlash from Kopassus and the ABRI Hijau faction, Wiranto desperately needed to keep Feisal Tanjung on side.

It seems that Feisal Tanjung wanted to lead the military’s strategizing on East Timor in 1999 and that Wiranto, willingly or because he had no choice, gave him a free rein. When Australian Prime Minister Howard advised President Habibie to plot a long-term path towards a referendum in East Timor, it was Feisal who chaired the key 25 January 1999 meeting that discussed Howard’s letter. It was Feisal, who had been involved behind the scenes during the Act of Free Choice in West Papua thirty years earlier, who chaired a March 1999 meeting that discussed the wording of the special autonomy proposal for East Timor. Major General Zacky Anwar, who was sent to East Timor in April 1999 to oversee the referendum process, was said to report to both Wiranto and Feisal Tanjung. However, Zacky Anwar’s relationship with Wiranto may not have been particularly strong because Wiranto had eased him out of a key position only months before. On 11 May 1999, when Zacky Anwar finally gained an official role in East Timor, it was as a member of P40KT, a team set up by Feisal Tanjung to ‘Secure and Make a Success of the East Timor Special Autonomy Ballot. In fact, secret communications intercepted by Australia’s Defence Signals Directorate show that most of Zacky Anwar’s reporting was to Feisal Tanjung. In effect this by-passed the formal chain of command.

After the UN mission arrived in East Timor in June 1999, Feisal continued to wield influence. A leaked 3 July 1999 Indonesian military document called for a large-scale coordinated plan for evacuation from East Timor and destruction of vital installations. The plan was written by Major General Garnadi, who worked under Feisal Tanjung in the Coordinating Ministry for Politics and Security. Wiranto played a role in sourcing funding for the militias, attending many meetings related to strategising for East Timor, and misrepresenting what he really knew when he spoke in media conferences. Feisal Tanjung appears to have been the mastermind.

Academic Geoffrey Robinson, who was in the UN compound in Dili in the June-September 1999 period, noted one claim that, “General Wiranto tried to order the withdrawal of the militias to West Timor before the ballot, but was unable to make his order stick in the face of opposition from within the TNI.” He admitted there remained doubt as to, “whether the post-ballot violence was ordered through the normal chain of command or not.”

One day Indonesians may learn how the chain of command really operated in East Timor and in other crimes of the 1998-2000 period such as the Jakarta riots and Trisakti shootings of May 1998, the Biak massacre of July 1998, or the Ambon conflict of 1998-2002. If it is later revealed that Wiranto was an instigator of these crimes, or even that he could have prevented them without facing a backlash from within the Indonesian military, he deserves full condemnation, and should be made to answer for his crimes. But if he simply failed to stop human rights abuses because the chaotic context of 1998-2000 forced him into political compromise with hardliners, that is a lesser sin.

Indonesia got through the difficult years of 1998-2000, transitioning from a dictatorship to a peaceful democracy rather than to disintegration. Wiranto, who juggled the interests of reformers and hardliners in the military, is a more complex person than the one-dimensional figure painted by human rights activists.

Dr Terry Russell worked as a teacher and aid practitioner in Indonesia for 15 years. He is currently based in Australia, working in the international aid sector (with an organisation that has no involvement in Indonesia).

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss