Unskilled workers are at risk of exploitation in the ASEAN Economic Community.

With a population the size of continental Europe (slightly more than 600 million people), but with half of its land and a fraction of its wealth, ASEAN comprises 10 sovereign countries with a rich range of cultures, languages, and ethnicities.

But, anyone who spends time in the region quickly realises how peoples’ lives in Southeast Asia overlap and clash together in a way which is totally non-dependent on the location of national boundaries.

Border areas have been historically a no man’s land. Used by peoples who identify themselves by ethnic identity rather than the nation state, these areas are far from the centres of authority and thus loosely controlled by the government.

Such conditions have historically encouraged trans-boundary movements of people, goods, and information from border areas inland towards urban centres. For decades governments have tried to track down and control crossings that their legislation deems illegal, but that for border peoples were valid.

Trans-boundary interactions have occurred undisturbed for centuries, following customs and bonds that geopolitical schemes have tried so hard to classify to make them fit into the nation-state discourse.

That’s why 2015 marked a real turning point for the region and ASEAN; after lengthy preparations, the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was established. It was the first step towards fully-fledged regionalisation.

The numbers for this economic community alone are revealing. It is the second-largest emerging economy after China’s, it grew by more than 300 per cent in two decades, ushering the Asian century on to the global stage.

This is what matters when it comes to changes in livelihood at the local level; the economy, or trade, dictates the way people move and interact. But, while many will focus on interpreting and predicting new macro-economic trends, few will try to understand how such changes influence the population.

It might be easy to show how augmenting regional trade is worth the change — although Free Trade Agreements, in place since 2010 and dominated by China and India, have had Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia’s eyebrows raised ever since.

Human insecurity is, however, the inevitable by-product of such dramatic change, and the abatement of borders is fuelling social unrest all over the region, especially when it comes to labour migration, and the movement of unskilled workers. Statistics show that 90 per cent of the 8 million economic migrants who yearly relocate within ASEAN are unskilled.

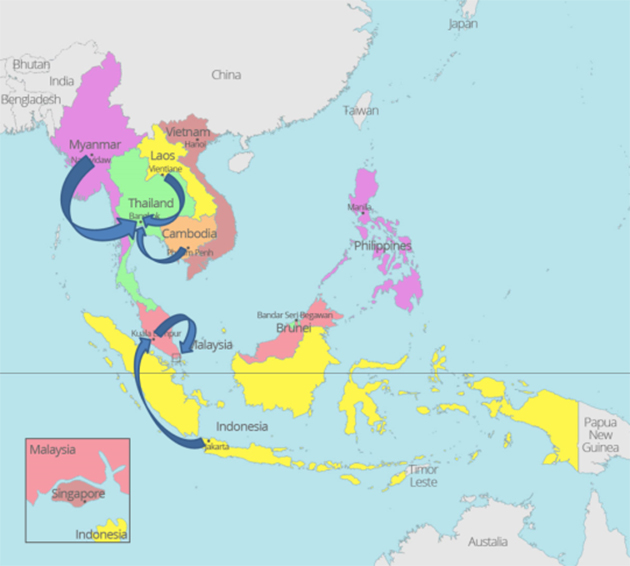

Remittances are a reliable indicator for understanding the flow of unskilled labour across the region. Analysing these reveals that the most beaten corridors are from Myanmar towards Thailand, from Indonesia towards Malaysia, from Malaysia to Singapore, from Laos towards Thailand, and from Cambodia towards Thailand.

Unsurprisingly, migratory flows target the richest countries in the bloc. At the same time, we cannot see any decentralisation of labour. Furthermore, of the total number of migrants, about two million are Burmese, one million Indonesians, and a further million each are Laotians and Cambodians. As such, we can see that these numbers make up the vast majority of that 90 per cent of unskilled labourers looking for jobs mostly around the urban centres of ASEAN’s richest nations.

Unsurprisingly, migratory flows target the richest countries in the bloc. At the same time, we cannot see any decentralisation of labour. Furthermore, of the total number of migrants, about two million are Burmese, one million Indonesians, and a further million each are Laotians and Cambodians. As such, we can see that these numbers make up the vast majority of that 90 per cent of unskilled labourers looking for jobs mostly around the urban centres of ASEAN’s richest nations.

Here then is the real challenge to the AEC vision. The population of destination countries is itself growing, and benefitting from higher levels of education and specialisation. If decentralisation of skilled labour does not occur, and if people from wealthier countries are not dispatched to help their developing neighbours, no matter how high the economic growth index, labour supply will choke demand in destination countries. Most of these unskilled economic migrants will end up feeding the already large portion of the urban poor.

The implications of this scenario might even be worse. At the inception of AEC in April 2015, the ASEAN Peoples’ Forum (the dialogue platform for civil society’s participation) warned the Assembly of the inevitable formation of a “stateless working class, with no bonds and no rights.”

The People’s Forum also highlighted that this would lead to an “unfavourable business environment for the skilled labour-force, thus downgrading standards and exacerbating the domestic tax burden” because it will increase “the number of temporary jobs already aggravating the precarious financial and social state of unskilled economic migrants.”These are perfect grounds for the proliferation of illegal activities, and criminal groups are already at work. Migration in the AEC is bound to become a heavily marketed phenomenon targeting the weak and most vulnerable — women and children. It is in fact already impossible for a migrant to embark on a cross-country journey without applying at one of the hundred employment agencies in the region, whose job is to ensure that you will be fully taken care of when you reach your destination.

All of this comes at a price. A contract is signed, and there begins the ordeal. Agents will agree to advance the costs of documents and travel, which are then deducted from the migrant’s first salaries. Unfortunately, there isn’t the slightest certainty that employers at the destination country will honour the contract, as job and immigration laws are far from standardised, and the market for unskilled labour is highly volatile.

Nonetheless, the bond between migrants and agents is therefore more of a patronage-like relationship that resembles human trafficking. It is, in fact, easy to imagine how such schemes fuel prostitution and illegal migration. The fact that women are increasingly involved in this phenomenon (both as victims as well as perpetrators) is also concerning.

The AEC experiment is still in its early days, and there are still high hopes that more democratic and inclusive participation will keep regionalisation on the right track. In particular, letting civil society have a more active role in the implementation of Mutual Recognition Agreements should ensure a less biased distribution of benefits deriving from freer movements of goods and people.

At the moment, more and more economic migrants try to circumvent the problem by presenting as refugees. In many cases, such acts not only require them to cheat death when they undertake perilous journeys, but are based on the hope of appealing to international conventions and being granted the right to stay.

Sadly, news reports tell us that Singapore, as well as Thailand and Malaysia, do not seem to be sympathetic to such gambles, quickly and forcibly repatriating refugees they don’t deem to be genuine, even against UN resolutions.

Gianluca Bonanno is Assistant Professor, Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University and Director of the International Peace and Sustainability Organization (IPSO).

This article is an edited version of an essay in RISE, the publication of the Torino World Affairs Institute (Twai).

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss