Bridget Welsh charts the major challenges to civil liberties across the region in 2016.

In reflecting on developments in 2016, attention has centered on events in the West or the Middle East, Trump’s presidential victory or the brutality in Aleppo. But closer to home, Southeast Asia has experienced worrying trends that have undermined human rights and fostered division. Overall, 2016 was not a good year for the region, as trends show greater challenges for civil liberties.

Vicious political attacks on civil society activists have risen, with greater violence. Cambodian activist Kem Lay was murdered in broad daylight in July. Filipino environmental activist Gloria Capitan in Bataan Philippines was murdered in the same month, while labor activists Orlando Abangan and Edilberto Miralles were killed the same week in September. In Malaysia Sarawakian indigenous rights activist Bill Kayong was shot point blank in his truck at a road junction in June. Serious questions remain about culpability in all of these cases.

Other attacks on activists were more clear-cut, with governments ruthlessly using all of their tools at their disposal to quiet dissent. Malaysian Bersih movement chairwoman Maria Chin Abdullah was arrested using Special Offences (Special Measures) Act of SOSMA for 10 days, along with other activists, notably student leader Anis Syafiqah Md Yusof. In Singapore youth Amos Yee was forced to seek political asylum in response to an apparent pattern of persecution. He was sentenced to six weeks jail ‘for wounding the religious feelings of Christians and Muslims’ following a similar arrest in 2015. Cambodia’s ‘Black Monday’ have also faced repeated arrests over the year for defending human rights. This pattern is evident in Thailand as well as, with Thai human rights lawyer Sirikan Charoensiri facing repeated intimidation, having been summoned after her testimony on human rights in Geneva in September. She was later charged with sedition. The hardline approaches often backfired, but not without activists having to sacrifice for their principles.

Going after opponents is becoming a regional norm. Junta-led Thailand led the way in arrests, particularly those challenging the August referendum on the military’s constitution. Others were not far behind. While Cambodia Prime Minister Hun Sen opted to end the year with a ‘truce,’ 2016 witnessed unprecedented arrests and verbal and physical attacks on opposition members. Opposition leader San Rainsy was exiled and not allowed to return to Cambodia, while co-opposition leader Kem Sokha was holed up in his office for months. Thailand’s democratically elected leader Yingluck Shinawarta, ousted by the military in the May 2014 coup, now faces a criminal case associated with her government’s rice subsidy scheme, while Malaysian opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim languishes in jail for a politically-trumped up conviction and is cruelly being denied proper medical treatment.

To reinforce efforts to dampen criticism, governments have tightened control over freedom of speech. This has come in two forms: charging people for criticism to instill fear and introducing tougher legislation.

Journalists have been on the frontline of the charges. In January, Timor Leste’s Prime Minister Rui Maria de Araújo launched a criminal defamation case against two journalists for a 2015 report regarding alleged tendering malpractice during his time at the Ministry of Finance. The original news article contained a factual error, which was later corrected in accordance with Timor-Leste’s press laws. The democratically-elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government in Myanmar has not been press-friendly either. In early October, journalists were convicted and fined for defamation in two separate cases. In November, after a report on rapes in Rakhine State, Myanmar Times reporter Fiona MacGregor was called-out by the president’s office spokesman and later sacked. In Malaysia, political conditions led to the closure of The Malaysian Insider and Malaysiakini’s editor Steven Gan being charged for simply reporting a story. Vietnam, however, tops the obstacles for journalists, even over the often deadly conditions in the Philippines. Vietnamese journalists were beaten for investigating a toxic chemical spill in July. In April seven bloggers were convicted in a week, reinforcing the long-standing crackdown on reporting alternative views.

The targets against free speech have increasingly been ordinary citizens, with Facebook comments in particular being used as the basis for arrest. In March, Thai anti-junta activist Sarawut Bamrungkittikhun was arrested for comments on his page Perd Praden (Opening Issues). The same month Theerawan Charoensuk was arrested for posting a red plastic bowl with Thai New Year greetings to former Prime Ministers Thaksin Shinawatra and Yingluck Shinawatra. Indonesian poet Saut Situmorang was sentenced for five months for his Facebook comments criticising Indonesia’s literary figures in September.

The scope of jurisdiction is widening. In May three Laotians were arrested upon their return from Thailand after making Facebook and social media comments critical of the Lao government while abroad. Criticism of the military is especially punished. In 2016, at least five people in Myanmar were imprisoned for Facebook posts deemed insulting to the military or government officials. This included NLD member Myo Yan Naung Thein who was charged for his posting criticising the military for ‘failing to defend the country’ in Rakhine State in November. Thailand’s military has been similarly hard core in responding to criticism online.

The curbs on free speech are also extended to traditional arenas. In February, six University of Malaya students were punished for holding a press conference. There is a chill in many campuses across the region as academic freedom and student activism is under threat. Parliament is also not a sanctuary. Opposition parliamentarian Rafizi Ramli was convicted for releasing documents associated with the 1MDB, receiving no meaningful whistleblower protection in the scandal involving Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak. A similar broad scope of interpreting criticism was evident in Thailand where a mother of a student activist Patnaree Chankij was arrested for acknowledging an email she received using the non-committal “ja”, colloquial ‘yes,’ to respond. Her son Sirawith Seritiwat is a student activist with Resistant Citizen and the New Democracy Movement.

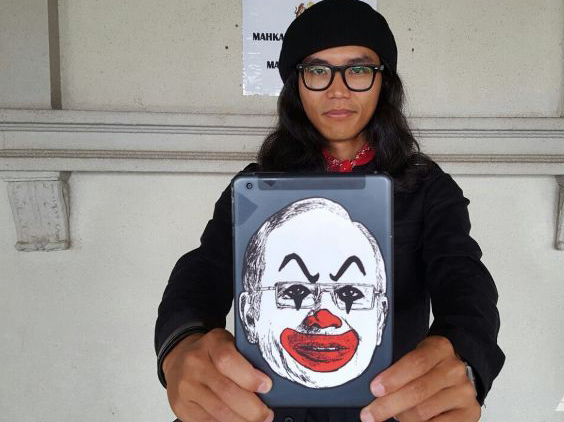

Political satire has been particularly hard hit by authorities. In May eight people were charged for mocking Thai Prime Minister General Prayut Chan-ocha in a Facebook post that included doctored photos and colorful memos. Political cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Ulhaque, or Zunar, was repeatedly arrested for showing his work, charged again with sedition against Malaysia’s prime minister. Street artist Fahmi Reza was also charged for depicting the Prime Minister as a clown.

To make their powers stronger, regional governments have tightened laws governing speech. Vietnam’s National Assembly passed broad sweeping legislation in March that would in effect criminalise ordinary journalist reporting. Before the referendum, a new law was passed in Thailand to ban campaigning against the military constitution or expressing opinions that were “inconsistent with the truth.” Activists were arrested for holding leaflets using this law in July.

In Singapore the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act passed in August broadening the conduct that can be penalised as contempt of court, a measure seen as chilling on political discussions. In December Thailand’s new Computer-Related Crime Act (CCA) gave wide powers to the government to restrict free speech, enforce surveillance and censorship, and retaliate against activists online. This follows Malaysia’s tightening of its online media regulation in March. Laws to restrict online speech have been commonly used, and are being contested. For example, Indonesia’s Law on Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) was curtailed by the Constitution Court in September. Elsewhere governments are opting to tighten the laws before they get to the courts.

Malaysian artist Fahmi Reza and his image of Najib as a clown. Photo: Syafiq Safian.

Along with restrictions on speech, another regional trend has been growing intolerance against minorities. The treatment of the Rohingya in Myanmar has captured the headlines, with egregious conditions in Rakhine State, a growing insurgency, persistent military power and intractable positions. Myanmar is not alone in its poor treatment of Muslims. In Indonesia non-Sunni Muslims are threatened. This year the Ahmadi faith was outlawed in the Indonesian province of Bangka Belitung, its mosque in Central Java was destroyed, and followers arrested in Lombok. Shiites were targeted as well, while members of the Gafatar organisation were torched in West Kalimantan and over 7,000 were sent for ‘reeducation’. Non-Muslims have also been targeted, with the blasphemy case against Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, or Ahok, the most well-known example.

Conditions in Malaysia and Brunei are also difficult, with overzealous conservative religious authorities limiting religious freedom. In Malaysia, the brutal treatment of Rohingya migrants in a camp discovered in 2015 remains unresolved, as no one has been prosecuted for the rapes, sale of organs and murders of over 100 people.

Fighting has increased in minority areas in Myanmar, especially in Shan and Kachin states. Peace has broken down in the Philippines in Mindanao with the squashing of the Bangsamoro Basic Law. The Moro region has seen a record number of kidnappings in the south, reaching 53 hostages and multiple beheadings. The situation in southern Thailand has also deteriorated with reports of torture and an expansion of violence outside of the southern provinces. These developments speak to the failure of non-violent conflict measures as governments opt for confrontation and force, exacerbating conflict.

Rather than enforce the rule of law, officials in some cases are taking law into their own hands. The most obvious example of this is the almost 6,000 extrajudicial killings in the Philippines for ‘drugs’. The optimism over discussions in Papua have also faded, with arrests returning as the norm. The Jakarta Legal Aid Institute found that over 2,200 people have been arrested for non-violent rallies between April and September alone.

Underscoring the decline in human rights are deeper political undercurrents. With its majority control over the Security Council, prominent role in ethnic conflicts and deep involvement in the economy, the military remains powerful in Myanmar. The military is gaining ground in Indonesia through appointments, while after the August referendum on the constitution the army is refusing to let go in Thailand. Autocrats are doing everything to stay in power in Cambodia and Malaysia. In the Philippines, strongman Rodrigo Duterte, elected in May, has brought a new low level to the nation’s discourse and leadership. With a contracting economy in most of the region, the pressures on leaders will likely increase, and this will spillover for rights.

Changing dynamics with great powers are exacerbating the region’s deterioration in human rights as well. China has pitted ASEAN partners against each other in its effective use of division and resources, and shown little interest in protecting rights. It is buttressing the power of autocrats and strongmen with lucrative infrastructure deals. With the incoming Trump administration, human rights are unlikely to feature in any serious manner from the United States. This comes after only lukewarm efforts (at best) by the Obama administration to meaningful address human rights. This trajectory places tougher burdens on those fighting for rights in Southeast Asia.

Despite all of the negative trends, however, 2016 showed that Southeast Asians are willing to step forward. Activists, journalists and ordinary citizens are not backing down from what is right. They are owning their battles and more young people are joining the fight for basic freedoms and principles. It is not easy by any means. However, the commitment and community of human rights advocacy remains strong and increasingly active, not only in opposition to gross violations but in fact a result of the growing egregiousness of the rights abuses themselves.

Bridget Welsh is a Visiting Professor at John Cabot University, a Senior Research Associate at the Center for East Asia Democratic Studies at National Taiwan University, a Senior Associate Fellow at The Habibie Center in Indonesia and a University Fellow at Charles Darwin University.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss