Despite the intense royalist indoctrination of the Bhumibol era it would be naïve not to imagine that at least some Thais draw inspiration from the country’s long republican tradition.

Thailand is typically understood as a deeply royalist country ruled by a highly revered monarch.

The king’s image is everywhere. The capital, Bangkok, is strewn with monuments to past kings. Countless streets, bridges, dams, universities, schools, army bases, hospitals, etc. are named after royalty. The calendar is full of royal holidays. Thailand has one of the world’s strictest lèse majesté laws which forbids criticism of the king and royal family.

Given all this it may come as a surprise that republicanism is deeply ingrained in Thailand’s political tradition. In fact, Thailand has one of the oldest republican traditions in Asia.

The first proposal to limit the absolute power of the monarch famously came in a petition to the king in 1885. It was drafted not by the European colonial powers but by a group of Thai princes. Though unsuccessful, this was among the first indigenous attempts to limit monarchical power anywhere in Asia.

In 1912, one year after the Chinese revolution ended 2000 years of imperial monarchy, the Thai authorities foiled a plot involving “thousands” to overthrow Siam’s monarchy. It was even said that lots had been drawn to assassinate King Rama VI. The plotters were split between republicans and constitutional monarchists.

As Copeland has shown, the Siamese press at the time mercilessly mocked the monarchy and aristocracy in a way that is unheard of today.

The People’s Party finally succeeded in ending Siam’s absolute monarchy in a bloodless coup on June 24 1932.

What is not widely acknowledged is the influence of republican thinking on the People’s Party, especially the leading intellectual force behind the movement, French-trained lawyer Pridi Phanomyong. It is clearly evident in the famous People’s Party Announcement Number 1, issued after the coup, which Pridi is credited with drafting:

On the question of the head of state, the People’s Party does not wish to seize the throne. It will invite this king to continue in his office as king, but he must be placed under the law of the constitution governing the country. He will not be able to act of his own accord without receiving the approval of the House of Representatives. The People’s Party has informed the king of its wish. We await his reply. If the king refuses the invitation or does not reply by the deadline, selfishly believing that his power has been reduced, then he will be judged to be a traitor to the nation. It will be necessary to govern the country as a republic [prachathipatai]; that is, the head of state will be a commoner appointed by the House of Representatives for a fixed term of office [my italics].

Royalist historiography which dominates the official interpretation of the events of 1932 downplays the role of the People’s Party, instead crediting King Rama VII with granting the gift of “democracy” to the Thai people.

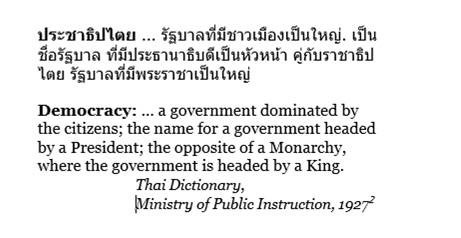

But as the highlighted sentence from the Announcement shows, the term “prachathipatai”, normally translated today as “democracy”, originally conveyed the meaning of “republic”.

In fact, as Nakharin has pointed out, in the original 1932 draft of the Announcement to eliminate any doubt the Thai word prachathipatai was followed by the English translation, “republic.”

Official dictionaries from this period, both Thai-to-Thai and Thai-to-English, also commonly translate the Thai word prachathipatai as “republic.”

Before 1932, Pridi himself had taught his law students that there were two types of “democracy” (prachathipatai): a country with a president as the head of government, as in France, or a government in which executive authority lay with a committee, as in the Soviet Union.

So Thailand’s democratic history has distinctly republican roots.

For that reason royalists later coined the phrase, “prachathipatai an mi phra maha kasat song pen pramuk” to describe Thailand’s political system. The phrase is officially translated today as “constitutional monarchy”, but its literal translation is “democracy with the sacred, great king as head of state”. Its real purpose is to erase the original republican associations of the word prachathipatai. Even the word “constitution” has been sacrificed, since placing the king “under” a constitution violates Buddhist spatial norms about the proper place of the king.

Following the failed Boworadet rebellion in 1933 the royalists were routed. King Prajadhipok went into exile and eventually abdicated. Other princes fled Siam or were imprisoned. The heir to the throne escaped to Switzerland. For a decade there was no king in Thailand. Military strongman Field Marshal Phibun Songkhram, who also had republican leanings, ruled as a virtual president. This was the closest Thailand has come to republican rule.

The story of the restoration of the monarchy after World War II has been told before. It culminates with the coups of Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat in 1957 and 1958, following which, with the support of the United States, the monarchy became the figurehead of a virulently anti-communist military dictatorship. As Somsak has pointed out, for the royalists “the threat of communism and the threat of republicanism were one and the same thing”.

From this period monarchy in Thailand became more than just an institution. It legitimised an ideology of submission and servility that lives on today.

Under this royalist-military regime the erasure of Thailand’s republican tradition from official history was completed.

Following the routing of the Communist Party of Thailand and the end of the Cold War the last traces of republican political thinking were expunged. As a result a generation of Thais have been estranged from their country’s republican tradition.

The political conflict that erupted in 2005 between Thaksin and the palace has now entered its eleventh year with no resolution in sight. Royalists repeatedly accuse the Thaksin forces of seeking to lom jao – “overthrow the monarchy”. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, pro-Thaksin parties have repeatedly won free elections.

The mainstream pro-Thaksin forces have consistently denied they have a republican agenda. For obvious reasons surveying republican sympathies in Thailand today is impossible. Yet despite the intense royalist indoctrination of the Bhumibol era it would surely be naïve not to imagine that at least some of them may draw inspiration from Thailand’s long republican tradition.

Patrick Jory’s new book, “Thailand’s Theory of Monarchy: The Vessantara Jataka and the Idea of the Perfect Man”, has just been published by SUNY Press. For details, including how to order the book, see this link: http://www.sunypress.edu/p-6222-thailands-theory-of-monarchy.aspx

For the full article on which this summary is based see, Patrick Jory, “Republicanism in Thai History”, in Maurizio Peleggi ed., A Sarong for Clio: Essays on the Intellectual and Cultural History of Thailand—Inspired by Craig J Reynolds (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), pp. 97-117.

For the full article on which this summary is based see, Patrick Jory, “Republicanism in Thai History”, in Maurizio Peleggi ed., A Sarong for Clio: Essays on the Intellectual and Cultural History of Thailand—Inspired by Craig J Reynolds (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), pp. 97-117.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss