Above all the political drama, two things stand out from Malaysia’s 2013 General Election. The first is the extent to which the electoral system is distorted; on a number of measures, Malaysia has among the highest levels of malapportionment in the world. The second is the extent to which those distortions constitute a clear partisan bias, which is responsible for transforming a 4% deficit in the popular vote for the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition into a 20% parliamentary seat advantage. Given the risk that these two factors present to political stability in Malaysia, the stakes for the upcoming redelineation exercises are remarkably high, especially in light of recent statements made by the former head of the Election Commission (EC).

Electoral systems can distort election outcomes in several ways. In Malaysia’s case, the most significant distortions are the result of malapportionment, where constituency size varies substantially across districts. In first-past-the-post (FPTP) parliamentary systems like Malaysia’s, this leads to votes in some districts being dramatically more influential than votes in other districts. For example, a vote in Malaysia’s smallest electoral district (Putrajaya with about 15,700 voters) is nearly 10 times as influential as a vote in the largest electoral district (Kapar with about 145,000 voters). This clearly doesn’t conform with the one-person-one-vote principle central to democratic theory. It is not just at the extremes that Malaysia’s system is ridden with malapportionment. Rather, there are significant distortions across the regional, state, and district levels. Using a widely accepted measurement of malapportionment, Malaysia scores among the highest in the world along with Zambia and Ghana.[i] This is not, contrary to occasional claims, an inherent function of the FTPT system itself, as other countries which employ the system – including the United States, Australia, the UK, Canada, Singapore, the Philippines, and India – all have significantly lower levels of malapportionment.

The results of this distortion are clear. Malaysia’s opposition coalition Pakatan Rakyat (PR) fared well in GE13. It won the popular vote by a 4% margin, which is greater than the margin in 3 of the last 4 US presidential elections. Its 7% margin in West Malaysia is greater than all but one US presidential election since 1984. It would not be a stretch to call a similar result a decisive victory in an established two party democracy. And yet Malaysia’s electoral rules transformed that 4% vote deficit for the incumbent BN coalition into a decisive 20% parliamentary seat advantage. In the simplest terms, malapportionment handed BN a strong victory in an election that it lost by most democratic standards.

Malaysia is unique in one important respect, however, in that its constitution includes a very vaguely worded endorsement of malapportionment in the form of an unspecified “measure of weightage” towards rural votes. The explicit justification for this is that low population densities in rural areas increase the cost and difficulty of maintaining adequate contact between constituents and representatives. Consequently, rural districts require a smaller number of constituents per representative. This aside, over-representing rural voters also safeguards the political domination of Malays and other indigenous bumiputera voters, who enjoy constitutionally enshrined privileges and still comprise a large proportion of rural voters. It is important to be clear, however: while the constitution allows for some level of overrepresentation for rural and potentially also Malay-majority districts, it makes no such allowances for an independent advantage towards one political party over another.

So what are we to make of the malapportionment in Malaysia? There is little question that its proportions have grown to extreme levels by international standards. But beyond that, there remains the important question of partisanship. Claims that the malapportionment is a function of the non-partisan overrepresentation of rural voters are regularly made by the BN and the Electoral Commission, despite ongoing protestations by a diverse group of commentators including opposition politicians, civil society groups like Bersih, and academics. In a recent article (How to Win a Lost Election: Malapportionment and Malaysia’s 2013 General Election)[ii] for a special edition of The Round Table focusing on GE13, I use newly available data[iii] on the voter density of electoral districts to test whether the evidence supports the claim that malapportionment is the result of non-partisan rural overrepresentation or systematic partisan bias in favor of the incumbent BN coalition. Specifically, I use statistical models to examine the independent effect of voter density, proportion of Malay voters, geographic location, and partisan inclination on the size of electoral districts.

The results are quite striking. Predictably, voter density does play a significant independent role in the size of districts – on average, the more dense a particular district, the greater the number of voters it contains. Surprisingly, when we control for voter density, the percentage of bumiputera voters in a district has no independent effect on district size. The key finding, however, is that after controlling for voter density and percentage of bumiputera, the partisan inclination of a district has a significant independent effect on the size of the district; at comparable levels of voter density and percentage of bumiputera, PR districts have roughly 20,000 more voters than do otherwise identical BN districts. This result holds whether we look at all of Malaysia together, or West and East Malaysia separately.

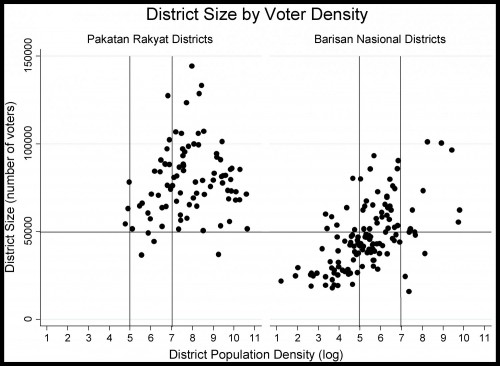

The figure below gives us a simple graphical depiction of the relationship between voter density and district size for PR and BN districts. The y-axis (vertical) captures the size of electoral districts in number of voters. The x-axis (horizontal) captures the density of voters on a logged scale, ranging from 1 (low-density rural) to 11 (high-density urban). The dots on the left depict districts held by PR, while the dots on the right depict BN districts. Two observations immediately jump out. First, a vast majority of low-density rural districts (lower left quadrant) are held by BN, while a large majority of high-density urban districts are held by PR. This corroborates many of the post-election commentaries. Second and more importantly, within the band of medium density districts (between 5 and 7 on the logged scale), BN districts are on average significantly smaller than PR districts; a majority of BN’s seats in that range are smaller than 50k voters, while only three PR seats fall below that threshold.

The interpretation of these data is straightforward. Voter density does play a role in determining district size. But there is also a clear independent effect of partisan affiliation, and that effect is substantial.[iv] At comparable levels of density and proportion of bumiputera, BN districts are smaller than PR districts by over 20k voters. The evidence simply does not support the claim that district size is the result only of non-partisan structural factors. Party politics matter and Malaysia’s electoral system has a deep systematic bias in favor of BN.

While malapportionment has been slowly increasing since limits on it were relaxed in 1962 and removed entirely in a 1973 constitutional amendment, the recent revelation that former EC Secretary (1979-1999) and EC Chairman (2000-2008) Tan Sri Abdul Rashid Abdul Rahman has officially joined Perkasa (the UMNO-aligned right-wing Malay rights group) sheds light on just how partisan the electoral system has become. Rashid, who oversaw the last three redelineation exercises as well as six general elections, stated that redelineation exercises – which are responsible for creating malapportionment – were carried out with the intention of preserving Malay political dominance. The evidence presented here, in conjunction with Rahman’s Perkasa affiliation, suggest that ‘Malay political dominance’ could instead be read as UMNO (and by extension, BN) dominance.

There is little question that Malaysia’s malapportionment is reason for concern. It raises serious normative questions about Malaysia’s democracy and reduces the credibility of election outcomes. By greatly amplifying the influence of BN-friendly voters in small districts, it also allows BN to maintain its grip on power without the support of broad segments of the fractured population. This bodes ill for reconciliation efforts and promises to introduce increasing political instability into the political system. For all of these reasons and more, it is no exaggeration to state that Malaysia’s political future hinges on the upcoming redelineation exercises, which are to be completed before the next general election. The current EC Chairperson, Abdul Aziz Mohd Yusof, has acknowledged some of the electoral system’s distortions and has emphasised his intention to carry out the redelineation exercise in a non-partisan manner. Time will tell whether GE13 proves to be the catalyst towards restoring the equity of Malaysia’s electoral system.

Kai Ostwald is a Ph.D candidate in political science at the University of California, San Diego.

[i] For an explanation of the measurement, see: Samuels, D., Snyder, R. (2001), The Value of a Vote: Malapportionment in Comparative Perspective. British Journal of Political Science, pp 651-671.

[ii] Ostwald, K. (2013), How to Win a Lost Election: Malapportionment in Malaysia’s 2013 General Election, The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs, pp. 521-532.

[iii] Greenberg, S., Pepinsky, T. (2013), Data and Maps for the 2013 Malaysian General Elections. Working Paper, Department of Government, Cornell University.

[iv] There is an endogeneity issue that requires addressing. See the full article for an explanation and my argument.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss