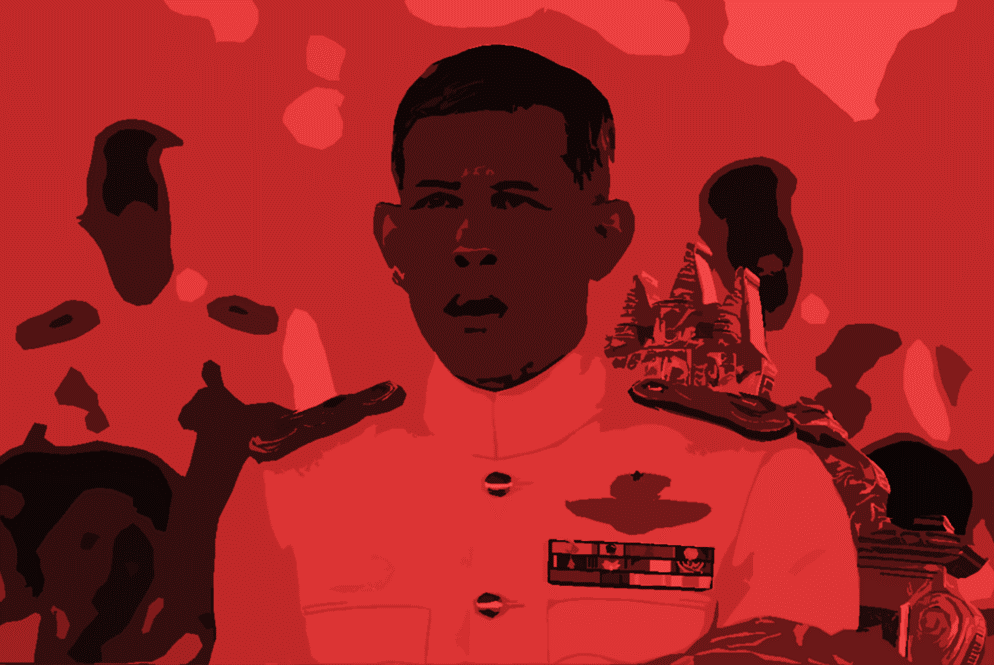

How is the new monarch of Thailand, Maha Vajiralongkorn, ruling his kingdom since the death of his father, the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej?

Fear.

The overwhelming success of Bhumibol’s reign has evidently become an entrapment for Vajiralongkorn, who has failed to follow in the footsteps of his much-revered father. Vajiralongkorn is the mirror image of Bhumibol. Based on this assessment, some analysts have expected Vajiralongkorn to be a ‘weak king’, precisely because of his lack of moral authority, divinity and popularity once enjoyed by Bhumibol.

Bhumibol’s moral authority was made a sacred instrument that underpinned his effective reign for seven decades. It legitimised his political position, so as to place it above what were perceived to be ill elements, including ‘dirty’ politics and ‘corrupt’ politicians. Members of the network monarchy had worked indefatigably to ensure the strengthening of his moral authority, through vigorous glorification programs in the media and national education, about the devoted king who strove for his people’s better livelihood. It was his moral authority which was partly exploited to justify the use of the lese-majeste law.

Now that Bhumibol has passed from the scene, a critical question emerges: how has Vajiralongkorn forged new alliances and eliminated enemies and critics in order to consolidate his reign?

Without his own charisma, or baramee, Vajiralongkorn has exercised fear to command those serving him instead of trusting or convincing them to work for him based on love and respect, as argued by a recent article of Claudio Sopranzetti. Vajiralongkorn has used fear to build order, perhaps similar to the way in which mafias, or chaophos, operate their empire.

Vajiralongkorn reigns as a monarch whose authority is based upon fear, and as one who cares little about people around him. Fear is a tool to threaten his subordinates and drive them to the edge to keep them compliant and docile. He has kept his subordinates in line with unnecessary, yet rigid, rules, from professing a cropped haircut style to a tough fitness regime. But such rules possibly reflect Vajiralongkorn’s own state of fear. He does not know who will betray him at the end of the day. His intimidating image is his only source of personal power — but he also realises how fragile it could be.

Even prior to the death of Bhumibol, Vajiralongkorn relied on fear for his own rearrangement of power. He allowed a faction under his control to purge another perceived to be disloyal to him. The cases of Suriyan Sucharitpolwong, or Moh Yong, Police Major Prakrom Warunprapha, and Major General Phisitsak Seniwongse na Ayutthaya — all of whom worked for Vajiralongkorn, most visibly in the ‘Bike for Mum’ project — reiterated that death could become a reward for those who breached his trust. Each of these individuals were given a nickname. For example, Phisitsak was called by Vajiralongkorn, Mister Heng Rayah (เฮง ระย้า), although exactly why he was named as such remained unknown.

Within Vajiralongkorn’s palace, Dhaveevatthana, a prison was built. The Ministry of Justice, during the Yingluck administration, announced on 27 March 2013 that a 60 square metre plot of land within Dhaveevathana was allocated for the building of what is now called the Bhudha Monthon Temporary Prison. This ‘temporary’ prison has been legalised, potentially allowing the king to detain anyone under its roof legally. Adjacent to the prison is a crematorium. Major General Phisitsak died inside the prison and was cremated there too.

His former consort, Srirasmi, has been put under house arrest in a Rachaburi house, shaved and dressed as a nun. Her family members and relatives were imprisoned on dubious charges. Pongpat Chayaphan, a former Royal Thai Police officer who was the head of the country’s Central Investigation Bureau, was convicted in 2015 from profiting from a gambling den, violating a forestry-related law, and money laundering. Srirasmi is his niece. Earlier in 2014, Police General Akrawut Limrat, a close aide to Pongpat, was also found dead following a mysterious fall from a building.

Vajiralongkorn’s estranged sons, Juthavachara, Vacharaesorn, Chakriwat and Vatcharawee — who live in exile in the United States with their mother Sujarinee Vivacharawongse, née Yuvathida Polpraserth — have been banned from coming home. These extreme punitive measures reiterated the fact that fear once again functions as a controlling device over his subjects, even those with royal blood.

Vajiralongkorn also reorganised the Privy Council, appointing new faces from the Queen’s Guard, to entrench his alliance with the junta. He has also let General Prem Tinsulanonda remain in his position of President of the Privy Council, arguably, as part of using fear to keep his enemy close to him, so that Prem could be closely monitored and work under his direct command. And recently, he punished one of his close confidants, Police General Jumpol Manmai, a former deputy national police chief, labelling him as the extremely evil official so as to justify the humiliation caused to him. Jumpol was arrested and imprisoned. His head was shaved, like Moh Yong and Prakrom, and was sent to undergo a military training within the Dhaweevattana Palace. Like Pongpat, he was found guilty of forest encroachment.

Meanwhile, some have been promoted, some demoted. Speedy promotions in the military and the police were enjoyed by the king’s new favourites. Those irritating him were thrown out — but before that, they were humiliated on the pages of the newspapers. Vajiralongkorn purged the entire Vajarodaya clan, one of the most prominent families of palace officials serving under Bhumibol. Disathorn Vajarodaya was stripped of his power in the palace, forced to re-enter a military training at the age of 53, and is now working as a house maid who serves drinks to guests of the new king. Meanwhile, Suthida Vajiralongkorn na Ayutthaya, a former Thai Airways air crew, was promoted to the rank of a general. She is currently the number one mistress of Vajiralongkorn. But the life of Suthida is not without competition. Colonel Sineenat Wongvajirapakdi, aka Koi, who is a nurse, is reportedly becoming his number one favourite. A video clip of Vajiralongkorn and Koi, both wearing skimpy crop tops barely covering fake tattoo wandering a Munich mall, was viral on the Internet.

In the political domain, Vajiralongkorn directly meddled in the drafting of the new constitution, requesting an amendment to boost royal powers. The changes included removing the need for him to appoint a regent when he travels overseas. More importantly, a clause that gave power to the constitutional court and other institutions in the event of an unforeseen crisis was removed. But by removing it, the king’s political role was significantly reinforced.

Because of his direct interference in Thai political affairs, it is naïve to assume that Vajiralongkorn is simply a mad king, clueless about running his kingdom. His meddling has unveiled his desire to solidify his power at this critical juncture in politics, forging ties with his allies while deposing his enemies and critics through brutal means.

Fear — for one’s own freedom, or one’s own personal safety — is a key weapon of Vajiralongkorn’s in keeping elites around him in line, alongside the longstanding use of the lese-majeste law to curb public discontentment against him. For instance, the military government chose to punish Jatupat ‘Phai’ Boonpattararaksa for sharing a BBC article on the biography of Vajiralongkorn, underscoring the use of fear to warn the public to stay away from his private life. Jatupat is the only person to be imprisoned for sharing the article.

On the eve of the recent Songkran holidays, the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society released an announcement to forbid the public from following, befriending and sharing content of three critics of the monarchy: myself, the exiled historian Somsak Jeamteerasakul, and former reporter Andrew MacGregor Marshall. Fear has now been ulitised at a national level, in cyberspace, to frighten ordinary social media users. In failing to obey the royal prerogatives, some could be jailed, like Jatupat.

But fear can fall away. Overused and frequently exploited, fear will eventually loose its spell. Exactly how long Vajiralongkorn will continue to count on fear to build up his power remains uncertain. What is certain today is the fact that Thailand is no longer a smiling country. It is a country in deep anxiety.

Pavin Chachavalpongpun is associate professor at Kyoto University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss