This is the second part to Jeremy Mulholland’s series on the KPK. For part one, click here.

In its current weakened state, Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) has become increasingly susceptible to political pressure and influence. In relation to the corruption cases now being investigated by KPK, selected targets for investigation and criminal penalties occupy positions of political power and wealth that are not at the top echelon of Indonesia’s ruling elites.

We only need to provide two examples of powerful members of Indonesia’s ruling elite whose behaviours are exempted from KPK’s enforcement net. KPK leaders are evidently keeping clear of the two most powerful members of Jokowi’s cabinet — Vice President Jusuf Kalla and Coordinating Minister of Politics, Law and Security Affairs Luhut Pandjaitan are engaged in a fierce power struggle against each other and their respective power networks are fighting over existing and new lucrative sources of slush funds.

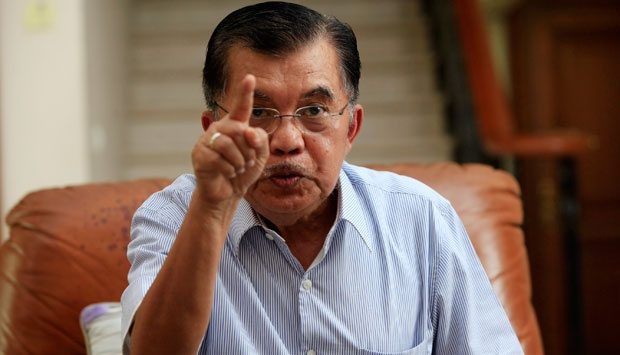

Jusuf Kalla

Jusuf Kalla supported revisions to the KPK law often using the pretext that anti-corruption efforts impede economic growth. However, the Freeport scandal revealed that in 2015 both competing political bosses Jusuf Kalla – heading a faction including Energy Minister Sudirman Said – and Golkar chair Aburizal Bakrie – and his faction including the then DPR chair Setya Novanto and oil tycoon Riza Chalid- vied against each other to dominate informal negotiations with Freeport decision-makers concerning the contentious issue of the renewal of Freeport’s mining contract worth more than US$40 billion.

Bakrie’s faction was also closely aligned with the Luhut Pandjaitan and Coordinating Minister of Maritime Affairs Rizal Ramli faction to gain direct access to and sway president Jokowi. Bakrie’s allies Setya Novanto and Riza Chalid met with the then Freeport Indonesia’s executive director Maroef Syamsoeddin, while Jusuf Kalla’s brother-in-law Aksa Mahmud and nephew Erwin Aksa (Bosowa group) met with the then Freeport McMoRan Chair James Moffett.

A conflict over ‘who gets what spoils’ led to a fully-blown corruption scandal. Even though the degree of complicity of both elite groups was the same, Freeport scandal’s timing and consequences allowed Kalla’s group to win that round of the game.

Fighting between these elite groups has surfaced once again in a corruption scandal centred on the state oil company Pertamina. Kalla’s faction, including the Energy Minister Sudirman Said and Pertamina’s current and former president directors Dwi Soetjipto and Ari Soemarno, directed the KPK to investigate Riza Chalid’s dominance in Indonesia’s oil and gas industry. At the heart of Riza’s dominance is the Singapore-domiciled Pertamina Energy Trading Limited (Petral), which plays a leading role in Pertamina’s international trade. Kalla’s group, through the use of the ‘Integrated Supply Chain’ (ISC) concept, have so far been unable to challenge Riza’s dominance.

In this context, Sudirman Said provided results of a forensic audit to KPK. The results may have been conducted independently by auditors KordaMentha, but were skewed to focus on the period 2012-14 which precluded involvement of Sudirman and his ally former Pertamina president director Ari Soemarno. The financial investigation revealed that Riza Chalid, through Global Energy Resources and Veritaoil, typically inflated the costs of crude oil and oil products to Pertamina thereby collecting extraordinary rents worth US$18 billion.

KPK chair Agus Rahardjo signalled he would not only establish a KPK task-force within Pertamina, but also investigate long term procurement contracts generating revenue streams flowing into Riza’s slush funds. As a result, KPK intensified efforts at investigating a Pertamina based commercial agreement with Riza’s fuel storage terminal, PT Orbit Terminal Merak (OTM). Riza’s ally, the then DPR chair Setya Novanto, officially demanded that Pertamina pay OTM’s (inflated) fuel storage costs.

Luhut Pandjaitan

While consistently supporting revisions to the KPK law and demanding the KPK not monitor the Aceh government bureaucracy and regional budget (APBD), Luhut Pandjaitan and close ally Rizal Ramli have also been rapidly accumulating large-scale slush funds.

According to accounts from Indonesia’s Tempo magazine and scholar Imam Prasodjo, these slush funds are amassed by alignments with palm oil tycoons. These businessmen include Martua Sitorus (Wilmar group), Sukanto Tanoto (Asian Agri), Franky Widjaja (Sinar Mas) and Surya Darmadi (Darmex Agro), who apply the cost-effective and premeditated practice of forest fires to expand their lucrative palm oil plantations.

With the hazardous side-effects of a regional smoke haze constantly attracting intense media scrutiny, public criticism and international condemnation, Luhut’s tight control of law enforcement has enabled him to threaten criminal sanction and land seizures against those companies he classifies as acting ‘illegally’. At the same time, informally, he holds out the ‘olive branch’ of political protection and favour in return for levies and gifted shares.

Luhut’s success is demonstrated by his ability to command ineffective ministers such as Forestry Minister Siti Nurbaya Bakar and Agrarian Minister Ferry Mursyidan Baldan to protect the anonymity of favoured companies involved in 2015 fires and then in 2016 getting many of these companies to join the so-called ‘fire free alliance’.

Second, Luhut and Rizal have also recently gained control over the development of several mega-tourist, electricity and gas infrastructure projects. Informal deals with these projects will translate into a torrent of informal funds flowing into their power network. This is exemplified by Luhut’s glowing appreciation for Rizal’s ‘brilliant’ proposal of the creation of a new tourist region – conveniently in Luhut’s home town of Medan, Sumatra – under the aegis of a single state agency, the Lake Toba Tourist Authority.

In early March, Rizal defeated Kalla’s faction (including Sudirman and a former KPK leader Amien Sunaryadi) by getting president Jokowi’s endorsement for the planned construction of a US$ 16 billion onshore liquefied natural gas refinery and power plant located in Masela, Maluku.

In May, Luhut’s power has been bolstered with the rise of Golkar’s new chair, Setya Novanto. Through the dispersal of informal funds and cars (justified as prizes in a Golkar golf tournament), Setya Novanto defeated Kalla’s preferred candidate Ade Komarudin and realigned Golkar with Jokowi’s government. This political result, contextualised with Tempo’s ‘Panama Papers’ revelations about an enduring friendship and interlocking shareholdings between Luhut and Jokowi, reinforces the bias associated with the way in which political power is currently used in the allocation of favours and projects. In these cases, the KPK is nowhere to be seen.

Conclusion

This political-economy analysis undermines oft-made claims that the KPK is functioning effectively and resisting the corrupt politico-business environment.

On 10 March 2016, new KPK Chair Agus Rahardjo argued that ‘KPK works independently and is not influenced by any interests… KPK doesn’t work in the political domain or quid-pro-quo (balas jasa). We are law enforcers, whatever data and evidence we receive will definitely be processed’.

However, ‘the ups and downs of KPK’s existence, crushed from every direction’ (to borrow the phrase of the late intellectual Adnan Buyung Nasution) is a product of intra-elite contestation and institutionalised corrupt norms of behaviour at the top of Indonesian democracy.

In this sense, the best analogy for KPK’s evolution and its relationship with successive presidents is Megawati as a mother who never wanted the ‘child’ (read- KPK), SBY as an abusive stepfather who lived through his child’s achievements, and Jokowi as the estranged and feeble uncle.

If the KPK is again perceived as overstepping the mark by investigating very senior powerholders in Indonesia’s ruling elites, the backlash will surely involve renewed attempts to revise the KPK law. The new KPK commissioners have every reason to tread warily because they are ‘on notice’. Over-reach could lead to the KPK’s destruction. The KPK’s mandate has always involved an implicit compromise. It has now become much more explicit.

Jeremy Mulholland is executive director of Investindo International and researcher in International Marketing at La Trobe University (jeremypm@hotmail.com). This article is a complementary piece to the following scholarly research; ‘The Politics of Corruption in Indonesia’ co-authored with Professor Howard Dick in Georgetown Journal of International Affairs (Volume 17, Number 1, Winter/Spring, 2016; https://muse.jhu.edu/article/615082/pdf).

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss