When President Rodrigo Duterte visited Beijing in October 2016, he came home with an agreement that earmarked US$24 billion worth of Chinese foreign direct investment and aid for the Philippines.

For many pundits and international relations scholars, Duterte’s returning with such an impressive haul of investment pledges could be explained by his decision to soften Manila’s stance in the long running dispute with China over claims to South China Sea waters. As Renato De Castro reflected on Duterte’s deals, “[The Philippines] become[s] dependent on Chinese aid … [and the] Chinese market… That would favor China (and) solve those disputes on Chinese terms, because China has economic leverage.” In short, the return of big ticket Chinese investments after Duterte’s conciliatory turn illustrated a simple logic for Southeast Asian political leaders: play nice with Beijing, gain investment and aid.

Rodrigo Duterte (seated) at a bilateral investment conference in Beijing, October 2016.

But such a framing reflects a widespread tendency to overestimate the importance of inter-state relations in determining the level and character of Chinese foreign investment, a tendency which impedes our attaining a more sophisticated understanding of the issue. Indeed, a look at the evidence shows that foreign relations cannot explain the varying patterns of Chinese FDI across different Philippine presidential administrations. In this post, I present a reading of the Philippine case more attuned to domestic politics and political economy, explaining the limitations of the state-centric analysis and presenting a complementary—and, I believe, better—analytical framework.

The limits of inter-state relations

Chinese foreign direct investments (FDI)—i.e. from the People’s Republic of China and Hong Kong Special Administrative Region— jumped to US$2.5 trillion worldwide in 2015. Supported by overseas development aid (ODA) policies in the forms of grant aid, concessional loans, commercial loans, export-import credits, and revolving credits, an estimated 30,000 Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private companies are currently operating or have committed to invest in the developing world.

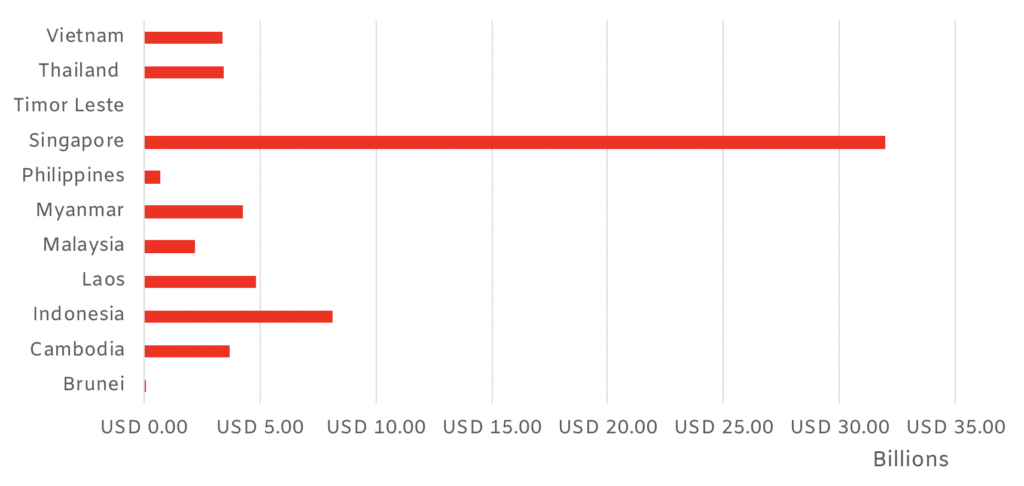

Figure #1—Chinese FDI Stock in ASEAN, 2015. Source: Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) of the People’s Republic of China (2015)

In 2015, Chinese FDI stock in the Philippines was US$712 million, one of the lowest national totals in all of Southeast Asia (see Figure #1). Malaysia and Thailand, countries with slightly wealthier economies, had four times the amount of Chinese FDI at roughly US$3–$4 billion. Indonesia, with a similar GDP per capita, acquired US$8.1 billion of Chinese FDI—ten times as much as the Philippines. Vietnam, smaller in overall economic size and in per capita distribution, also attained four times the amount of FDI as the Philippines.

Those who argue for the importance of institutions and bureaucracies might point out that weak Philippine institutions explain its relative underperformance in attracting Chinese FDI. But Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar—countries with perhaps higher rates of rent seeking and lower levels of state capacity—acquired higher amounts of Chinese investment.

For their part, international relations scholars generally point to the South China Sea dispute, Manila’s sympathy towards the United States’ role in the region, and the legacy of former president Benigno Aquino III’s poor relations with Beijing in explaining the low levels of Chinese investment in the Philippines. As realist theory would propose, China uses aid and investment to elicit political concessions. This assumes that if the Philippines agreed to China’s territorial demands, aid and investments would have increased. Since the Philippine government during Aquino rejected China’s territorial demands, it therefore makes sense that investment stagnated. As such, when Duterte reversed the course of China’s relations with the Philippines, these scholars again drew on state interests to explain the potential increase of FDI.

But the pitfall in this theory is the assumption that states are the main actors in determining the flows of FDI. The relationship between Philippine and Chinese leaders is surely important, but it ultimately falls short of explaining the variations in the types of investments, and across different Philippines presidential administrations.

Four puzzles geopolitics can’t answer

To understand why we need a more sophisticated analytical framework to understand the shifts in Chinese investment in the Philippines, let us consider a few key puzzles which a state-centric analysis doesn’t help us solve.

First, despite expanding diplomatic relations between China and the Philippines during the Gloria Macapagal Arroyo administration, why did investments remain low at the end of her term?

Arroyo’s administration embarked on a joint maritime venture with China in the South China Sea, initially circumventing Vietnam through a bilateral agreement with the PRC. But despite growing political ties with Beijing, Arroyo’s administration eventually cancelled the two biggest Chinese FDI projects—the North Rail train line and ZTE Corporation’s proposed National Broadband Network. The South Rail train was similarly cancelled, even before it had begun.

These cancellations were not isolated incidents, but part a trend seen across the whole economy. The Jinchuan Non-Ferrous Metal Corp and ZTE respectively planned to invest billions of dollars in the Nonoc Mines in Surigao del Norte and Diwalwal mine in Compostela Valley. In agriculture, the Arroyo government signed 18 land lease agreements with Chinese state and private agribusiness companies. From extractive industries to land, China was also ready to invest in banking and financial services. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and the Philippine government reportedly almost reached an agreement for the bank to invest billions and open more than 30 branches across the Philippines.

But at the end of Arroyo’s term, all of these big ticket Chinese investments had not come to fruition. Indeed, the State Grid Corporation of China (SGCC) saw the only successful investment through the purchase of a 40% stake in the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines. If inter-state relations were the most important variable in explaining the rise of Chinese investments, why did most of these investments fail in a benign diplomatic context under Arroyo?

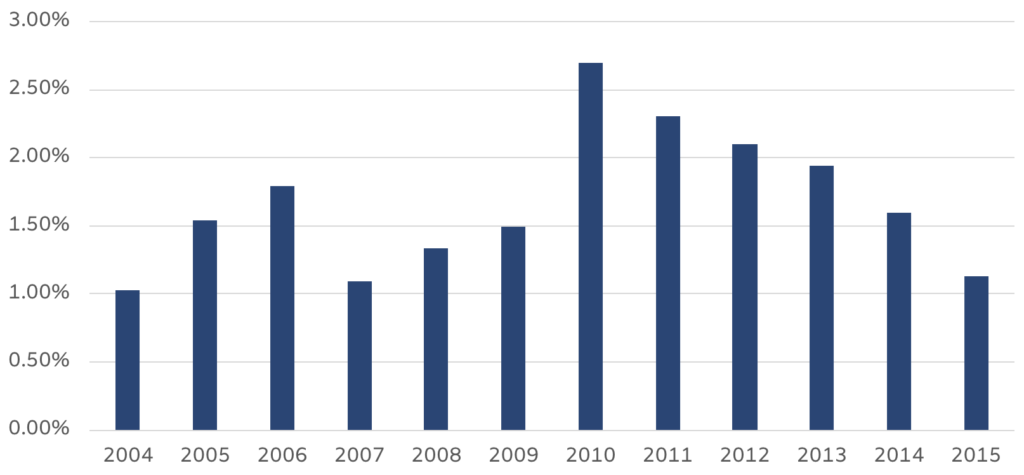

Figure #2: Proportion of Chinese FDI Stock in the Philippines vis-à-vis other ASEAN states. Source: Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) of the People’s Republic of China (2010, 2015)

Second, a more accurate measure of investment shows that Chinese FDI actually grew during a period of tense relations during Aquino’s term (see Figure #2). To properly gauge whether or not FDI on aggregate was higher or lower, a proportional measurement rather than absolute comparison, is more accurate. Because of the overall amount of Chinese FDI continues to increase annually worldwide, US$100 billion in 2006 may be something different in 2016. As such, proportional measurement captures the relative share that countries acquire annually within the overall amount in that year.

Using Chinese Ministry of Commerce data, Aquino received a (rounded off) average of 2.0% of all Chinese investment in ASEAN during his term compared to Arroyo’s 1.5%. Because of the South China Sea issue, one can even hypothesise that investments would have been even higher had inter-state relations remained cooperative. If the health of diplomatic relations were the most important determinant of FDI, Chinese investment would arguably have been lower on Aquino’s watch.

To be fair, the diplomatic relationship might well explain the absence of big ticket investments during Aquino. But the expansion of smaller projects during his term—mainly from private investors with little-to-no formal help from Chinese development or aid agencies—needs to be explained by something else.

In a recent paper, I argued out that the improvement of state capacity under Aquino explains this increase in smaller-scale Chinese investment. Some point out China’s refusal to offer big ticket investments to elicit concessions from Aquino’s government (based on my interviews, however, there are conflicting accounts of what China really offered Aquino after the Scarborough shoal incident.) While the former president missed out on the high-profile infrastructure and corporate investment projects on the scale of a ZTE or ICBC, the increasing presence of investors operating relatively independently of the Chinese state helped boosted the Philippines’ share of total Chinese investment in ASEAN.

Third, the logic of inter-state relations too often assumes that the party-state has command and control of Chinese SOEs. For IR scholars, the party-state’s decision to grant aid and encourage investments to the host state elicits the participation of SOEs. While some of these scholars recognise the SOE’s relative autonomy, they nonetheless assign greater analytical weight to the party-state because of guaranteed financing, the labour requirements, and material sourcing conditions.

While the party-state has the power to appoint the heads of “elite” SOEs, many of these still maintain some degree of operational and financial autonomy. Rather than a top-down relationship between the party-state and the SOEs, negotiations, compromise, and shared governance characterise the relationship of the two. Indeed, one can argue that the party-state has more power over major path breaking decisions, but everyday governance or smaller resolutions are left to the SOEs: as China scholars have shown, Chinese SOEs do have some degree of autonomy to negotiate and compromise on the direct orders of the party-state. In other words, SOEs do not necessarily follow the active inducement of the party-state and can modify the parameters of their engagement. Conversely, SOEs can also invest in governments that the party-state politically ignores at the international level.

Fourth, the focus on the party-state ignores the how the nature of Chinese SOEs’ overseas host partners influences investment pathways and decisions. Anthropologists and sociologists have pursued these place-based explanations. One of my ongoing projects examines the difference that Philippine coalition partners make to the success or failure of Chinese FDI projects. The failed ZTE, North Rail, and ICBC projects were championed by Arroyo officials. The mining and agricultural projects were spearheaded by various government departments but had to get the support of regional and local elites. In contrast, the SGCC—as mentioned, the only successful big ticket investment of the Arroyo era—was pushed by the most powerful Philippine economic elites. SGCC’s decision to work with these particular Philippine economic elites was not born from the Chinese government’s dealings with Arroyo, but from its own relatively autonomous decision to work with powerful Philippine private actors and invest in a technically sound business venture.

An alternative argument: elites and social mobilisation

While other academics proposed more specific place-based explanations of Chinese FDI, I propose approach that splits its focus between elites on the one hand and social movements on the other. This explanatory framework can travel across administrations.

A focus on domestic political forces reveals why, during Arroyo, inter-elite competition and social mobilisation from her administration’s opponents forced her to cancel the ZTE, Cyber Education, North Rail, and South Rail Projects. Intra-elite competition among the president’s own local-level allies hindered the Jinchuan Non-Ferrous Metal Corporation’s investment in the Nonoc mines, ZTE in the Diwalwal mine, and 18 land lease agreements with Chinese agribusiness companies. Arroyo’s own party members resisted Chinese mineral and agriculture investments due to the distributive implications on their rent-seeking activities, as well as on their local popularity. Arroyo’s inability to temper her own elites’ rent-seeking activities led to the failure of ICBC’s goal to establish operations in the Philippines: my interviews with insiders revealed that the Philippine representatives in the negotiations wanted equity in some of the planned branches, which ICBC declined to entertain.

A design image of the North Rail projet, Luzon. (Photo: North Rail)

Social mobilisation during Arroyo’s time also erupted because of multiple rent-seeking scandals, her inability to compromise with civil society actors, and her unpopularity among elites. Philippine civil society organisations are independent or align with either of the two major groups that reflect the ideological rifts within the left in the country: the rejectionists’ repudiation of revolution, and the reaffirmists’ reassertion of the Communist Party of the Philippines’ goal to radically alter Philippine society. Both the major “rejectionist” and “reaffirmist” left wing camps mobilised thousands of people during Arroyo’s second term to oppose the major Chinese deals. At the end of Arroyo’s term, only a small fraction of the investments promised during her term were realised.

Likewise, while tense bilateral relations under Benigno Aquino might explain the absence of big ticket Chinese investments during his administration, intra-elite competition within his cabinet led on its own to his administration’s combative stance towards China. At the start of Aquino’s term, Chinese foreign investment was targeted to fund more than 10 major projects. Aquino himself visited Beijing in 2011 and acquired the commitment of the Chinese government to provide more US$13 billion worth of aid and investment.

My interviews with former Aquino administration officials revealed that between the start of Aquino’s term and the flare up of the Scarborough shoal issue, intra-elite competition in Aquino’s own cabinet was intense. Aquino’s own administrative elites were deeply divided over their positions on Chinese investments, the prosecution of Arroyo and her officials, and the selection of Philippine economic elites to spearhead Public Private Partnership (PPP) projects.

This helps explain why big ticket investments were absent during Aquino, but small investments expanded exponentially. Aquino’s government appeared inclusive at the start, incorporating key leaders of the “rejectionist camp” and leading to the muting of social mobilisation. Aquino’s policies, bolstered by Arroyo’s fiscal reforms, also improved the Philippines’ credit rating score, leading to an increased capacity for domestic Philippine firms to borrow from capital markets. A more predictable business environment and the absence of popular mobilisation explain why many Chinese and non-Chinese businesspeople invested in the Philippines.

Finally, and though this may change in the coming years, the tendency for Duterte appears to be the muting of both elite competition and social mobilisation. Except for the holdovers of the Liberal Party, the majority of Philippine elites moved to Duterte’s camp after his election in 2016. The absence of a strong opposition bloc, such as existed during Arroyo and Aquino’s terms, makes Duterte’s government more durable. Popular mobilisation has also been muted. Some in the reaffirmist groups were initially incorporated in, or gave a chance to, Duterte’s government. More of them have begun mobilising in recent months, but it remains to be seen whether they will intensify further. The rejectionists’ capacity to mobilise was stifled. Some of them were incorporated in the elite Liberal Party while some of them are still recovering the organisational capacity to mobilise meaningfully against Duterte.

As Philippine elites and most of the population appear to be united behind Duterte’s banner, his government has the freedom to spearhead and implement Chinese foreign investment with little opposition from political elites. As a result, Chinese FDI is back in the strategic sectors of transportation, energy and infrastructure.

Duterte threatened to shut down Philippine Airlines’ operations at Manila International Airport if its oligarch owner didn’t pay his tax arrears. (Photo: Chrisgel Ryan Cruz on Flickr, Creative Commons)

In October 2017, China and the Philippines agreed on a US$9 billion loan for the Philippine National Railway’s Bicol Express, which will connect the Southern Luzon provinces to Metro Manila. China has also been tapped to build the Mindanao Railway Project in President Duterte’s home province. Economic elites in the previous administrations have been able to block Chinese FDI projects in order to monopolise key sectors. Today these elites are fearful of the Duterte government’s capacity to cripple their businesses via the state or social media. For instance, Duterte

Ahok and the rise (and fall?) of state capital

Forget oligarchy. Ahok's governorship, like Jokowi's before him, has been a boon for state enterprise.

In sum, the shifts in the roles of rent-seeking elites, and the prominence of popular mobilisation against Chinese FDI, has had a far greater effect on the nature and scale of FDI flows from China to the Philippines than have questions of foreign policy. Though previous scholars have pointed out the roles of corruption and political opposition in obstructing Chinese FDI, examining the empirics of Chinese projects more closely, with a focus on the political coalitions and power balances that accompany them, will help us develop a generalisable theory as far as the Philippine experience is concerned. Whether or not this explanation travels across different national contexts is another question, and remains an important challenge for researchers as Chinese investment becomes an increasingly important feature of the politics and political economies of countries across the world.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss