Andy Buschmann has collated data from a range of protest movements in Myanmar from 2011 to 2014. The numbers paint an interesting picture of political change and democratic reform.

After decades of isolation, Myanmar now finds itself in a period of social, economic and political change. With the coming to power of a quasi-civilian president, Thein Sein, in February 2011, far-reaching reforms were set in motion.

Since then, many observers have seen Myanmar in a transition towards democracy. However, it is not merely elections and a parliament that make up a representative democracy — basic civil liberties and civil engagement are also substantial components. A question that has remained understudied in the case of Myanmar is how these critical aspects have altered?

At a bare minimum the right to free expression, as well as freedoms of association and assembly need to be upheld in democracies, so citizens can develop points of view independent to the state and express these publicly. Such liberal rights are an essential condition to many dimensions and institutions of representative democracy, including free elections. But they are also fundamental to allowing a civil society to develop, in which groups articulate collective challenges to the state and, in this way, apply “pressure” for further reform in the direction of democracy. Furthermore, the freedom of expression, association, and assembly are part of universal human rights that represent the substantive concept of the rule of law.

So how can these basic civil liberties be expected to have changed in a political transition? For the least, they should have made considerable progress. In Myanmar, a positive evolution of civil liberties should be recognisable in practice from at least 2011.

In theory this evolution has been taking place. The military junta, the so-called State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), had, with Order No. 1/1988, originally banned the exercise of basic civil liberties in January, 1988. These rights were however introduced again after almost a quarter century with the signing of the new 2010 constitution.

But, in authoritarian regimes it is not unusual to preserve civil liberties on paper, namely in their constitution, while at the same time curtailing and tracking their practical exercise. For this reason it is important to take a look at whether civil liberties are practically exercised — in the form of public protests for example. This form of protest presupposes freedom of speech, assembly and association, permitting people to protest, organise, assemble and articulate their points of view. Protest assemblies are thus a good indicator of whether and how civil liberties are being practiced (and how the state responds towards such practices).

Drawing on data from the Myanmar Protest Event Dataset, containing 185 protest gatherings that took place in Myanmar between February 2011 and the end of 2014, four key findings are clear.

Table 1: Principal Variables (Demonstrations and Strikes)

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| N =185 | 17 | 62 | 33 | 73 |

| ∅ Participants | 530 | 672 | 440 | 1062 |

| Length of protest (Modus) | < 24 hrs | 24-48 hrs | 5-7 Days | 1-2 Weeks |

| Number of groups named as organizers | 3 | 6 | 6 | 30 |

| Serial protests | 1 (5.88)* | 25 (40.32)* | 18 (54.54)* | 24 (32.87)* |

| Arrests | 4 | 115 | 51 | 140 |

* Absolute Count (relative Count). Data Source: Myanmar Protest Event Dataset, Buschmann (2016)

Table 1 shows the distribution of certain primary variables taken from the data set. What is clear at the outset is that protest activities have increased over time. The number of demonstrations and strikes increased more than fourfold from 2011 to 2014. At the same time, the size of the protests doubled over roughly the same time period. While protests in 2011 were primarily of short duration (under 24 hours), the majority of protests in 2014 were longer-lasting protest “camps.” This is reflected also in the frequency of serial protests –protests directly related to previously held protests. As for the protests’ geographical distribution, unsurprisingly, the majority of protests took place in cities, while only some took place in more rural areas.

These numbers demonstrate that basic civil liberties have become increasingly preserved. What is even more promising is that not just the quantitative aspects of protest activities have changed but also the qualitative characteristics. Particularly noteworthy, is that over time more NGOs, other movements and groups have openly characterised themselves as protest organisations. The National League for Democracy (NLD), which has held governmental power since March 2016, as well as its youth arm, was, implicated in only 10 per cent of all protests, making it clear that it was not simply just the NLD who conducted protests in Myanmar.

In 2013 and 2014 “Single Issue Movements” — groups pursuing one specific objective — also emerged as organising forces. An example of this is the “Committee to Deter Moving of the Gems Marketplace,” which in 2014 sought to block relocation of a market in Mandalay. That more groups are identified does not mean that overall more civil engagement is taking place — it may mean that already existing actors are “self-identifying,” and are being more open about their aims. However, both trends suggest an overall increase in breathing space.

In terms of focus, there has been a trend towards critical topics and issues of pluralism. Especially since 2013, protests have increasingly dealt with human rights and land grabs. Overall, one can assume from the data that leeway for civil engagement has increased over time.

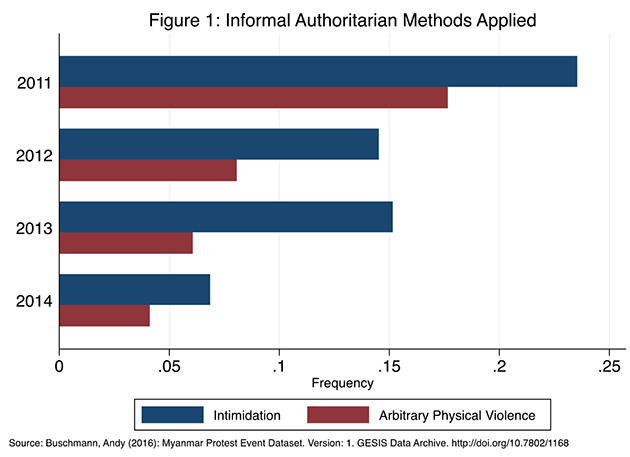

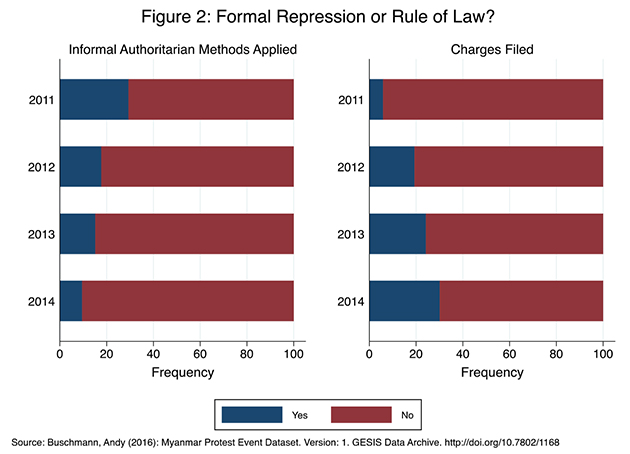

As for assessing the stability of the rule of law, the question is how the state’s behaviour towards protest participants has changed? While more and changing civil engagement implies that repression is probably a thing of the past, it might have simply become “better hidden”. As Graph 1 makes clear, brute force tactics targeting, and intimidation of protesters, which I call ‘informal authoritarian methods’, has clearly declined.

These informal authoritarian methods were in many cases still being deployed in 2014. In particular, the intimidation of protesters by representatives of state security forces was essentially still ongoing. Above all, and particularly in 2013, targeted intimidation tactics took place in relation to demonstrations against the violent putdown of protest camps at the Letpadaung copper mine in November, 2012. By 2014 the application of these informal but autocratic methods had however clearly decreased. This finding is obviously positive so far as it goes. Countering this, the following graph shows what amounts to an opposing trend in the number of protester arrests.

Arrests for breaches of the law are first and foremost a formal tool of states, and those based on the rule of law. Closer analysis of laws serving to justify detainment of protest participants nevertheless shows that in Myanmar these fall far short of international human rights standards (see for example Article 12 of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Law No. 15/2011, also know as the “Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law”). Until recently, it was thus possible for peaceful protest participants to be sentenced to several years in prison simply for distributing “false information.” Although the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law has for example been reformed several times and a number of repressive stipulations removed, the number of imprisonments is nevertheless rising.

On 31 May 2016, parliament passed renewed reforms of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law. It remains to be seen if in the future imprisonments connected to peaceful protests will fall or whether other laws will simply be used as grounds for court decisions and imprisonments (for example Paragraph 505b of the Criminal Code or the Telecommunications Law, which permits sentences of up to three years in prison for ‘defaming’ the government).

Up till 2014, progress. But what comes next?

Since Thein Sein’s ascension to office and the consequent introduction of reforms, Myanmar’s protest activity has grown in both quantitative and qualitative terms. Since 2014 arbitrary force against protesters has gone down, a sign that the development of basic civil liberties has taken a positive turn. And without question, laws against protest participation are being reformed. For this reason, since the internationally lauded elections of 2015 and turnover of power to the new NLD government in 2016, it is to be expected that repression has also increasingly receded after 2014. For this to be proved we await the empirical evidence.

Andy Buschmann studied Comparative Politics at the Humboldt University Berlin, the City University of Hong Kong and the University College London. He has been been focusing on political transitions, democratisation and social movements research.

The full analysis of protest in Myanmar can be found in this working paper. The dataset, including a methodology report and coding scheme, can be found on the GESIS Institute’s website.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss