Report of the first Joint meeting of the Asian Society for the History of Medicine (ASHM) & History of Medicine in Southeast Asia (HOMSEA), Jakarta, 27-30 June 2018

The first joint meeting of the Asian Society of the History of Medicine (ASHM) and History of Medicine in Southeast Asia (HOMSEA – https://homsea.net/) took place between 27 and 30 June 2018 at the new building of Indonesia’s National Library in the heart of Jakarta. It was sponsored by the Indonesian Academy of Sciences (AIPI). Sixty-five scholars from eleven countries presented their research at this meeting, which attracted over 150 participants. Topics of discussion included colonial medicine, psychiatry, malaria, medical pluralism, bioethics, Indonesia’s 1965 mass killings and associated trauma, urban sanitation, leprosy, zoonotic diseases, tuberculosis, medical education, nutrition, and Cold War medicine. Several papers explored the linkages between medicine and politics, especially during the Japanese occupation, the Cold War, and the way in which public health became enmeshed in nation-building projects of the postcolonial state.

Prof. Sangkot Marzuki delivers his plenary address. Source: Supplied

The plenary address was given by Professor Sangkot Marzuki, the President of AIPI. He investigated the legacy of colonial medicine in the Dutch East Indies after decolonisation by tracing the history of the Eijkman Institute for Medical Research, which was established in 1919. Professor Marzuki analysed the tumultuous years of the Japanese occupation (1942-1945), and the Institute’s history during the Indonesian struggle for independence. He paid special attention to the career of prominent Indonesian physician Achmad Mochtar, the first Indonesian director of the Institute. The Japanese made Mochtar into scapegoat for a mistake they had made in the production of vaccines elsewhere, which resulted in the death of over 1,000 forced labourers.

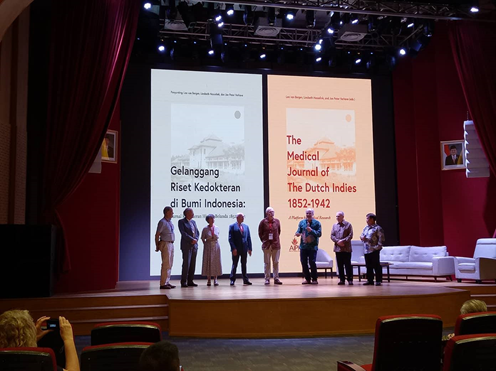

Professor Marzuki’s plenary speech was followed by a panel on the history of the Medical Journal of the Dutch East Indies, which was published between 1852 and 1942. After this panel, two edited books on the same topic were launched.[i]

Several authors who wrote chapters in the edited volume on the Medical Journal of the Dutch Indies on stage. Source: Supplied

Several noteworthy papers were presented. Three presenters examined malaria as a site of colonial and postcolonial contestation in both Malaya and Indonesia between the 1930s and the 1950s. James Collins’ exploratory paper looked at the social history of medical knowledge in the Dutch East Indies and independent Indonesia through a close study of malaria pamphlets dating back to the colonial period, the Japanese occupation, and the Sukarno era. A comparative study of the lexicon of colonial and postcolonial texts indicate ways in which the Dutch and the Japanese—and later, the postcolonial Indonesian state—co-opted malaria eradication into their political agendas.

Of the nineteen panels, eight were dedicated to Indonesian medical history. During the third plenary session, doctoral student Dimas Iqbal Romadhon (University of Washington) presented a laudable paper in which he used the Madurese folktale Bangsacara-Ragapadmi to analyse the kaleidoscopic understandings of leprosy in the Dutch East Indies and the limitations of colonial medicine. Jennifer Nourse (University of Richmond) offered rare insights into the consequences of decolonisation for medicine. She discussed the opening of a new medical school at Hasanuddin University in Makassar in 1956. Shirish Kavadi (Symbiosis International University) presented an empirically-rich paper that chronicled the history of the Indian Cancer Research Centre in Bombay. Medical decolonization was the underlying theme of his paper.

Transnationalism in health was the underlying theme of the panel “Interregional Contact and Collaboration.” Hong Sookyeong (The National University of Singapore), through the prosopography of Japanese physiologist Uramato Masasaburō (1891-1965), traced the linkages between science, national vitality, and the role of medicine in Japanese society in the period prior to the Pacific War (1942-1945). My own paper contextualised the niche physicians occupied in postcolonial Indonesian science during the 1950s. Xiaoping Fang (The National University of Singapore)offered a nuanced analysis of the 1961 cholera pandemic in Southeast Asia in the context of transnational politics, while John DiMoia (Seoul National University) traced the significance of the Vietnam War (1965-1973) in forging a South Korean-Japanese collaboration directed towards Southeast Asian nations in the realm of Family Planning and Population Control

The last panel, “Tuberculosis and Zoonotic Diseases,” was comprised of three disparate papers dealing with the historical development of pulmonology in Indonesia, the problem of mental health in Plantungan, and the study of collective memory around zoonotic diseases. Amurwani Lestariningsih (Head, Indonesian Presidential Museum) investigated how Plantungan, formerly a leprosy hospital during the colonial period, was used to house prisoners who had been members of Gerwani (Indonesian Women’s Movement, affiliated with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), accused of involvement in the murder of Army generals on 30 September 1965. In her presentation, Lestariningsih noted that these women prisoners were stigmatised as “ideological leprosy” patients and were indoctrinated in the state ideology (Pancasila) as a part of psychological rehabilitation. Lestariningsih noted that despite efforts by these political prisoners to erase the stigma associated with their involvement in the PKI, trauma continued to be a part of their everyday lives.

The conference banquet was held at City Hall, on the invitation of the governor of Jakarta. Source: Supplied

Breaking the Colonial Hypnosis: Radical Physicians and Medical Nationalism in the Dutch East Indies

Hans Pols proposes a new perspective on the history of colonial medicine from the viewpoint of indigenous physicians.

Hopefully, the next joint meeting (yet to be scheduled) will see the increased participation of scholars from mainland Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East. Although most individual papers drew heavily from the archives and addressed very specific themes, larger perspectives were often left unexplored. The conference theme—continuity and change between colonial and post-colonial medicine—naturally was too broad to offer definitive answers. The organising committee must be commended for encouraging young scholars from less-affluent parts of Asia to write their own histories, in a field hitherto dominated by Western scholarship.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss