In the tiny Southeast Asian nation, outsiders are still looking in and for a place to call home. Alana Tolman reports.

With the annual March sitting of the Legislative Council of Brunei (LegCo) the plight of the stateless residents of Brunei Darussalam has been brought, once again, to the surface.

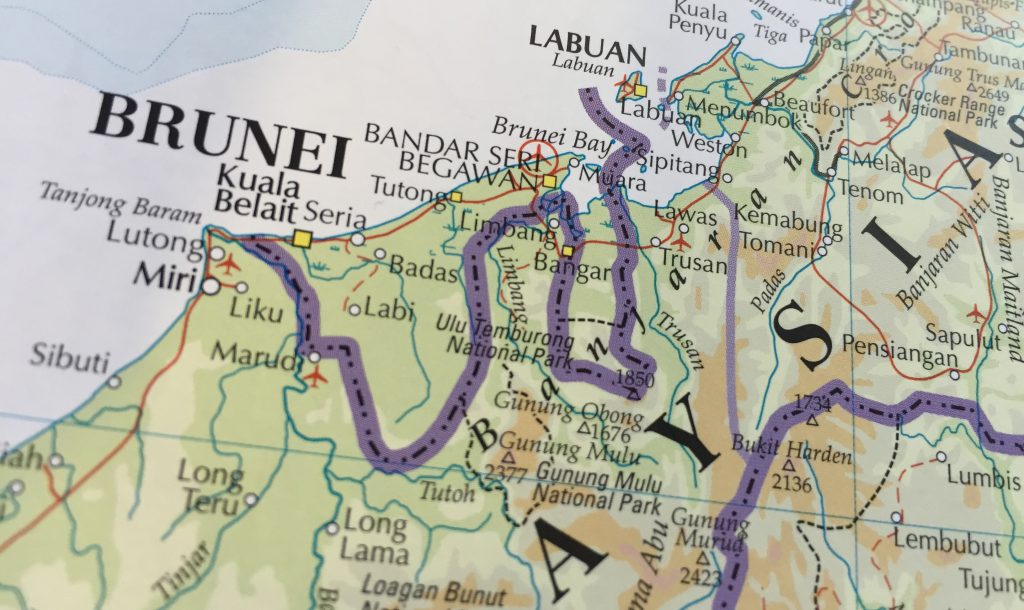

Many ethnic Chinese residents of Brunei have lived in the kingdom for generations, accounting for 15 per cent of the population. Yet, due to difficult and slow bureaucratic measures around immigration, they remain permanent residents, not citizens – they are essentially stateless.

Locally, the term ‘red IC’ – referring to the colour of national identity card given to permanent residents — is used to denote Brunei’s stateless permanent residents. Foreigners receive green cards and citizens receive yellow cards [a colour that lends itself to ‘golden ticket’ jokes]. These cards are necessary for every aspect of administration in the country – from enrolling in school to taking out a phone plan. Those without a yellow IC certainly feel the effects. The major telco does not allow people without a yellow IC to take out Internet plans, government scholarships for education are restricted and even social prestige is linked to your ‘colour’.

These disadvantages affect expatriates and Malaysians living long-term in the kingdom, but those most impacted are those who hold no passport. In lieu of a passport, stateless permanent residents are issued with a Bruneian International Certificate of Identity. While this certificate theoretically allows international travel, many nations are sceptical of the strange document and do not accept it – if they do it is with strict conditions. It is not hard to find workers who can’t be promoted within their company, as they can’t attend a specific training session that will be held in a nation they are barred from, or a family who has been questioned at a foreign airport for simply trying to take a vacation.

According to the Brunei Nationality Act 1961, a person residing in Brunei would be eligible for registration as a Bruneian national if the person has satisfied five conditions: the person has a proficient knowledge of the Malay language, able to speak it proficiently, has been examined by a Language Board on the Malay language, is of good character, and has taken the oath of allegiance.

However, these language standards are incredibly difficult to meet, as the multiple criteria allow for more reasons to reject an applicant’s competency claims. As standard Malay taught in school and Brunei Malay spoken on the street are linguistically different, failure to display considerable skill in either will prevent you from being registered as a citizen.

On 12 March, The Brunei Times published an article regarding the calls made by stateless people to the government. The callers were born and raised in Brunei and had previously sat citizenship tests, but were yet to hear back from the Department of Immigration regarding an oath-swearing ceremony. They had been waiting for years for a response, causing significant turmoil in their business, residential and family prospects – given non-citizens cannot own land in Brunei.

During the session of LegCo on the 10 March, Minister of Home Affairs Yang Berhormat Pehin Orang Kaya Seri Kerna Dato Seri Setia (Dr) Awang Hj Abu Bakar Hj Apong was questioned regarding the timeline for those who are seeking citizenship. Setting a timeline would be ‘very difficult’, he said, due to legal considerations, but did not elaborate on the nature of those considerations.

On 12 March, LegCo member Yang Berhormat Pehin Kapitan Lela Diraja Dato Paduka Goh King Chin – a respected advocate for the Chinese-Bruneian community – proposed to the Minister that the laws regarding citizenship be amended. His proposal included the granting of citizenship for stateless residents born in the kingdom that aged over 60. He also noted that before independence all residents of Brunei held a British passport, however after independence only ethnically Malay residents were granted citizenship. He spoke to the successful examples of Australia, Canada, Malaysia and Singapore where all residents were granted citizenship. This principle was not enacted in Brunei as it was a British protectorate, not colony, and thus was administered differently.

The Minister said that Chinese-Bruneians had an opportunity to apply for a streamlined citizenship process during the independence period, pointing out that as the Brunei Nationality Act 1961 predates independence in 1984, Chin’s arguments were irrelevant to the reality of the law.

“In conclusion, I feel confident in the National Citizenship Act, it is important for Brunei Darussalam in the long-term, and that I feel there is not yet a need to amend the Act,” the minister said.

Many claim that these conditions are simply used as legal way of discriminating against non-Malays, in an effort to preserve a false myth of homogeneity and tightly control who is ‘Bruneian’. This preservation is particularly important in regards to legitimising the state philosophy of ‘Melayu Islam Beraja’ or ‘Malay Islamic Monarchy’ [MIB], which permeates every aspect of the government and society.

The practical and existential difficulties associated with living with a stateless status have caused mass migration to a number of countries, causing a brain drain and potential capital flight. More cynical commentators claim that this is certainly not accidental, and these continued delays in the bureaucratic process are not haphazard at all, but a tool being expertly wielded.

Alana Tolman is an Asian studies/arts student at the Australian National University, and spent 2015 in Brunei as a New Colombo Plan fellow.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss