In tourism brochure clichés, Myanmar is often referred to as the last jewel of Asia. After fifty years of isolation under military rule, the newly open Southeast Asian nation conjures quaint images of the last untouched frontier in a shrinking world. Although we must remind ourselves that such romanticisation can be misplaced, given the authoritarian regime was a harsh reality rather than a luxurious abstinence from modernisation, many foreigners are curiously enthusiastic about visiting the country.

As an undergraduate focusing on Myanmar studies and the Burmese language, across my degree I have had numerous friends approach me to discuss plans to visit the country, famous for its glittering pagodas, ancient temples and rich cultural diversity. When people learn I study Myanmar, they often gush to me about their own experiences in the country. From backpackers I have chatted with in cheap bars in Cambodia, to wealthy club-goers smoking cigarettes outside expensive nightclubs in Singapore, almost everyone had a positive story to share.

However, recently the tone surrounding this conversation has changed. When hairdressers, university peers, strangers at parties or uber drivers ask me what I study, their first question is now about the Rohingya crisis, or negative feelings stemming from media coverage of the situation.

A lot of this discussion has focused on whether it is ethical to visit Myanmar, given recent widespread attention to the mass exodus of the Rohingya from Rakhine state. People do not want to be seen as financially or ethically condoning this traumatic situation—who wants to look back across history and say they supported what has already been called a genocide?

Therefore, it is worth speculating on two things: how this most recent wave of international outrage could dent Myanmar’s tourism figures, and whether foreigners should boycott the country, for fear of lining an authoritarian pocket.

Tourism growth is important for Myanmar’s government. For some background, it is difficult to accurately gauge tourism statistics in Myanmar. In 2014, Myanmar claimed to receive 3 million international tourists. However, at least two-thirds of this figure were day-trippers from Thailand, China, India, Laos and Bangladesh. The number peaked in 2015 at 4.68 million. Unsurprisingly the following year, total tourist figures dropped dramatically to 2.9 million when conflict in north and north-eastern Myanmar rendered day-tripping more difficult.

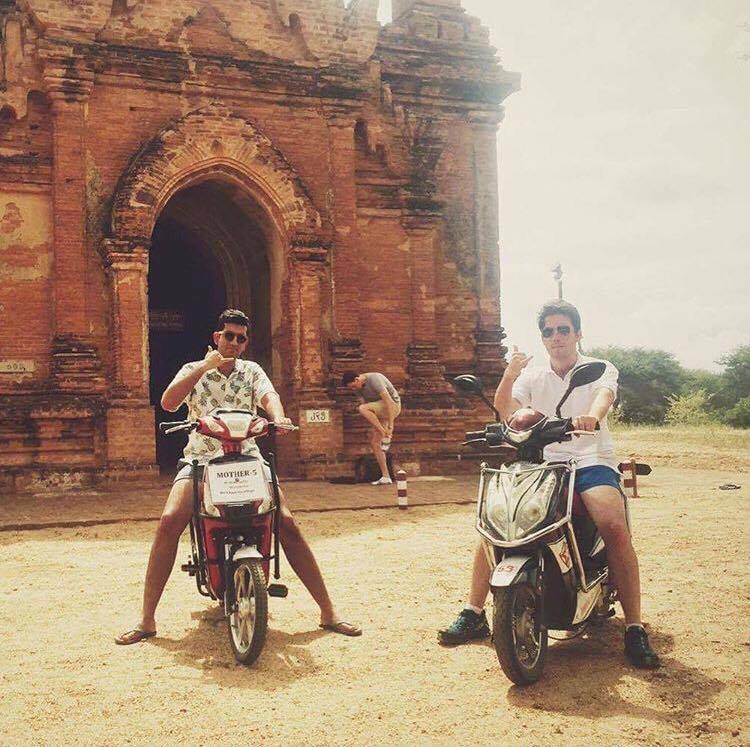

Australian National University students pose on e-bikes in famous tourist destination, Bagan (Photo: Harry Needham, ANU, Karan Dhamija, ANU)

A different measurement of tourism in Myanmar has been airport arrivals—this figure rose from 593,000 in 2012 to 1.08 million in 2016. Yet only 48.2 percent of those arriving in Yangon International airport in 2014 did so on a tourist visa, and it is estimated only 50-60 percent of arrivals in 2016 were purely for leisure. Measuring the sale of tickets at Shwedagon Pagoda, Myanmar’s most famous tourist attraction, revealed 505,351 tickets were sold in 2014—far from the three million tourists statistic—and in 2016, 600,000 tickets were sold, a contrast to the 2.9 million total tourist figures.

The Myanmar Ministry of Tourism plans to accommodate 3.5 million tourists by the end of 2017, and claims to have hosted 2.27 million tourists from January to August 2017. Given the difficult in knowing if tourism is even really booming to begin with, in evaluating the impact of the Rohingya crisis on Myanmar’s nascent tourism industry by the end of 2017, we should be cautious to not make sweeping claims about how exactly figures did or did not drop, and instead carefully examine airport arrivals, ticket sales to sites like Shwedagon Pagoda and Bagan, and day-trip percentages to gauge the real impact the crisis will have on Myanmar’s 2017 tourism figures. Currently, some coverage suggests the crisis has taken a toll on hotel bookings, particularly visits to Rakhine-based attractions such as Ngapali beach and Mrauk-U, but only time will reveal the true impact.

So, is it ethical to visit Myanmar? Most people asking me this question are concerned for two key reasons—they do not want to financially assist the regime’s conduct towards the Rohingya, and they do not want to be seen as morally endorsing the Rohingya crisis, or at best, being complacent to it.

With regard to lining the wrong pockets, opponents of a tourism boycott argue that tourism infrastructure was mainly government-owned in the past and such a case could be made, however today hotels, restaurants, guides, drivers, hawkers and vendors are privately owned and employ ordinary people. Accordingly, a tourism boycott would have little impact on the government while adversely impacting many who have built a livelihood around tourism. Others may argue that the government still owns substantive cogs in the tourism machine, such as airlines, or that it will benefit from tax revenue raised via tourism. Regardless of what you think, there is lots of literature suggesting economic sanctions in Myanmar never really had an impact in its democratic transition, so it is tough to conclude that a tourism boycott for economic purposes would now suddenly change the government’s attitude.

But what about more generally visiting Myanmar—is chowing down on Shan noodles and taking a selfie outside Shwedagon Pagoda normalising the Rohingya exodus? I think there are numerous factors why this is not necessarily the case.

Reverting back to avoiding the Myanmar people is one of the worst things we can do. Transitioning from a politically oppressive society with little access to information—to most of the country having Facebook within a few years—means the spread of misinformation and mistrust is particularly potent in Myanmar. Even within Myanmar, understanding of the Rakhine situation has been poor due to a history of travel limitations. In a global era of “fake news”, one of the most worthwhile tools we have is human relationships. To the common person in Myanmar, exposure to other norms will not come from catchy think-pieces, it will come from human interaction.

We should also keep visiting Myanmar because even beyond the Rohingya crisis, democracy and rule of law in the country is very fragile. A recent speaker I witnessed described the environment in the country as a collective PTSD. As a young person who has been to Myanmar many times, including with several Australian friends, I think cross-cultural interactions have been very valuable in prompting all of us to be more open to reframing our thoughts, especially if thinking is embedded in historical trauma.

And most of all, I have had people from Myanmar take me more seriously when they know I have bothered to get to know their country. Passionate strangers on Facebook or Twitter with contrarian political beliefs to mine considerably open up when I can blurt out some basic Burmese, reference my time in the country, and express an opinion as someone with a deep fondness for Myanmar, as opposed to looking to win a moral battle for ego points. Therefore, I hope to keep encouraging those around me to spend time in the country and with its people, now more so than ever.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

Mish Khan is a fourth year Asian Studies and Laws honours student at the Australian National University and the 2016 New Colombo Plan fellow to Yangon. She is currently based at Yangon University and can be reached at [email protected].

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss