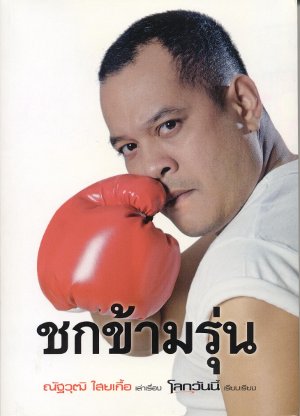

Daily World Today [lok wan ni], comp. Punching Above My Weight: Nattawut Saikua Tells his Story [chok kham run nattawut saikua lao ruang]. Bangkok, To Patak, 2009. 303 pp. In Thai.

As the latest episode in Thailand’s political crisis lurched toward its blood-stained finale earlier this year, Nidhi Eoseewong wrote in Matichon Weekly about the Red Shirt leaders. Nidhi’s columns during the crisis were always relevant to what was happening on the streets and in the barracks, but he tended to approach the issues from unexpected angles. In this case, he pointed out that whereas most of the Red Shirt protestors and their leaders came from the north and the northeast, three of the core leaders – Veera Musikapong, Jatuporn Phromphan and Nattawut Saikua – were from the south. All three held the crowds spell-bound with their words that drew laughs and applause. They spoke with passion, wit and rhetorical flourish; their language had the steady rhythm of a drum beat. In his experience, Nidhi said, southerners are not shy about speaking up, and if they get their hands on a microphone, they are reluctant to relinquish it. The Red Shirt rallies were given huge energy by the oratorical powers of the speakers with the southern accents.

Punching Above My Weight was published after the violent Songkran demonstrations in April 2009 that forced the closure of the ASEAN summit in Phattaya. Based on soft questions tossed up in a series of interviews by Daily World Today, a newspaper dedicated to open expression and economic globalisation, this is the story of Nattawut Saikua’s journey from southern provincial boy to big city political handyman. In the end pages more than a dozen relatives, friends and Red Shirt leaders testify to his natural abilities as a leader, team player and performer. He comes across as an unpretentious, likeable, down-to-earth guy who enjoys working for the cause. My translation of the title does not capture all the nuances of the Thai, but I’ve decided on it for what it reveals about Nattawut. He is afraid of no one.

The youngest of the three southern Red Shirt orators, Nattawut (b. 1975- ) grew up in his mother’s care in Nakhon Si Thammarat where two of her relatives, her father and her younger brother, were village headmen and became fatherly role models for him. Nattawut calls them nak leng, which he distinguishes from gangster, because they had to be tough to survive in the district. Typical of nak leng, they cultivated wide networks of friends and allies, a talent that Nattawut has inherited. In his youth Nattawut was a rascal, and to make ends meet while studying for his university entrance exams he ran a card casino out of his dormitory where the daily takings sometimes amounted to 8,000 baht. His group of friends in the south was known for its prodigious beer consumption.

The man was born to hold a microphone. A champion debater during his school years who gave his first political campaign speech at sixteen, Nattawut worked his way through university in the employ of Apichat Dumdee, a voice coach and communications adviser from Krabi famous for his oratory. As Nattawut’s reputation as a speaker and presenter grew, he found he could make a living with his natural gifts. Before he entered politics, he earned as much as 25-30,000 baht for an appearance. In addition to a communications degree, Nattawut also holds a Master’s of Public and Private Management from the National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA).

After an unsuccessful campaign for MP in the Chat Phattana Party in the 2001 election, Nattawut was drawn into Thaksin Shinawatra’s Thai Rak Thai Party (TRT) where he, Jatuporn and Veera formed themselves into a faction of their own. He uses the term wang (palace) for factions in TRT as well as the more common mung (lit. mosquito net). The southerners became the three amigos or kloe, a southern word for mate or buddy, and served as media specialists for TRT and its descendent parties, the People’s Power Party and the Puea Thai Party. The southerners had a role in the 2007 establishment of the People’s Television channel (PTV) and in the Truth Today talkshow that began in 2008 during the government headed by Samak Sundaravej. Nattawut’s television performances and his position as government spokesperson for Samak in that year made him a national celebrity. Officially he was only deputy spokesperson, but Samak, no mean wordsmith himself, became a fan of Nattawut’s way of putting the government’s case and came to rely on him.

Two chapters are specifically concerned with former prime minister Police Colonel Thaksin Shinawatra whom Nattawut did not know well when he was working for the TRT. After the September 2006 coup, when Thaksin was forced to remain abroad, the three amigos along with Nattawut’s wife, Siritsakun Saisa-ad, and Jakraphop Phenkae visited Thaksin in London where they met the former prime minister at 555 Park Lane near Hyde Park. In the mid-1950s Thailand had an interlude of street politics known as the ‘Hyde Park’ movement, named after Speaker’s Corner in London’s Hyde Park, and Nattawut jokes with his friends about being Hyde Park speakers. The entourage gleefully accepts Thaksin’s offer of a ride in his Rolls Royce, while the former prime minister and his party follow behind in the van rented by the visitors. Nattawut defends Thaksin against the charge that he alone is bank-rolling the Red Shirt movement. Contributions come from many benefactors and from public collections.

The question comes to mind in reading this book of how to characterise Nattawut’s political thinking, because little of that thinking is on display here. He praises former prime minister Police Colonel Thaksin Shinawatra’s democratic principles in general terms but has nothing to say about TRT’s policy achievements while in government such as the grants of a million baht to villages or the 30 baht health plan. There is nothing about what the parties stand for, and no discussion of a political program or vision for the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), and nothing, at least in this book, to suggest that he sees the Red Shirts as heirs to the October generation of the 1970s.

For Nattawut, Thailand’s political problems stem from the intransigence of the amatya, the term used for bureaucratic polity which also implies the Thai-style elite establishment including the Privy Council, the network monarchy and the army. He denounces the asymmetrical distribution of power and the injustices that stem from it. The amatya has all the power, and the people have none, despite the fact that the land belongs to the people, not to the amatya. The three southern amigos have always been vehement critics of the 2006 coup and the structure of power behind it. If only General Prem Tinsulanond, the president of the Privy Council, and General Surayut Chulanont, the prime minister in the year after the coup, would have stepped aside from their positions and let the people have their say, ‘we’ would have stood down, Nattawut declares at one point. He and other Red Shirt leaders were jailed briefly in 2007 for asserting that General Prem had been behind the coup. Nattawut is today, once again, a political prisoner.

In his Matichon column about the southern orators, Nidhi compared their language to food flavours. Nattawut’s speech is like clear tom yam soup that villagers make – spicy, vinegary and salty all at once, with a hint of sweetness and the strong aromas of lemon grass, kaffir lime leaves and fresh hot chilli peppers. Nattawut has made a career out of his peppery language ever since his school mates vied to have him on their team for class presentations. He is a talented, entertaining mass communicator whose commitment to the causes he works for is unshakable, because he is afraid of no one.

Reviewed by Craig J. Reynolds

Published originally on New Mandala, 27 October 2010

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss