Many have argued that religion played a decisive role in the defeat of former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok). Ahok was a Christian in an overwhelmingly Muslim city. According to an exit poll conducted on Election Day, over 70% of voters in the Jakarta gubernatorial election were satisfied with the job he had done in office. But, perplexingly, nearly 50% of these voters did not vote for him. Marcus Mietzner and Burhanuddin Muhtadi term this group “satisfied non-voters” and point out that 54.5% of them cited “religious identity” as the decisive issue in the election.

Why did Jakartans base their votes on religious identity, rather than policy? In other words, why did religion play such a decisive role in the election?

Many analysts (see: here and here) have pointed to the role of religious leaders in pushing voters towards Anies. The practice of campaigning through mosques and mushollas is widespread. In 2004, the government outlawed the practice under UU No 32 Tahun 2004. But parties continue to enlist the support of religious leaders who use their bully pulpit to advocate for certain candidates. In May, in a nod to the practice, Vice President Jusuf Kalla called on religious leaders and politicians to abandon the use places of worship for campaigning.

So if politicised sermons are thought to influence voters, then what happens when actual polling stations are located in or around houses of worship? On election day in Jakarta, 390 voting booths (Tempat Pemuntungan Suara, or TPS) were erected in and around religious establishments like mosques and mushollas.

This is worrying on at least two counts. First, asking voters to cast their votes in religious establishments might heighten the importance of religion in their decision. The effect of having a religious leader literally over one’s shoulder might be substantial, for example.

Second, holding voting booths in religious establishments might also deter religious minorities from voting. This is understandable. Particularly after tumultuous campaigns in which religion played a central role, minorities might choose to stay home might rather than cast their vote in a foreign place of worship.

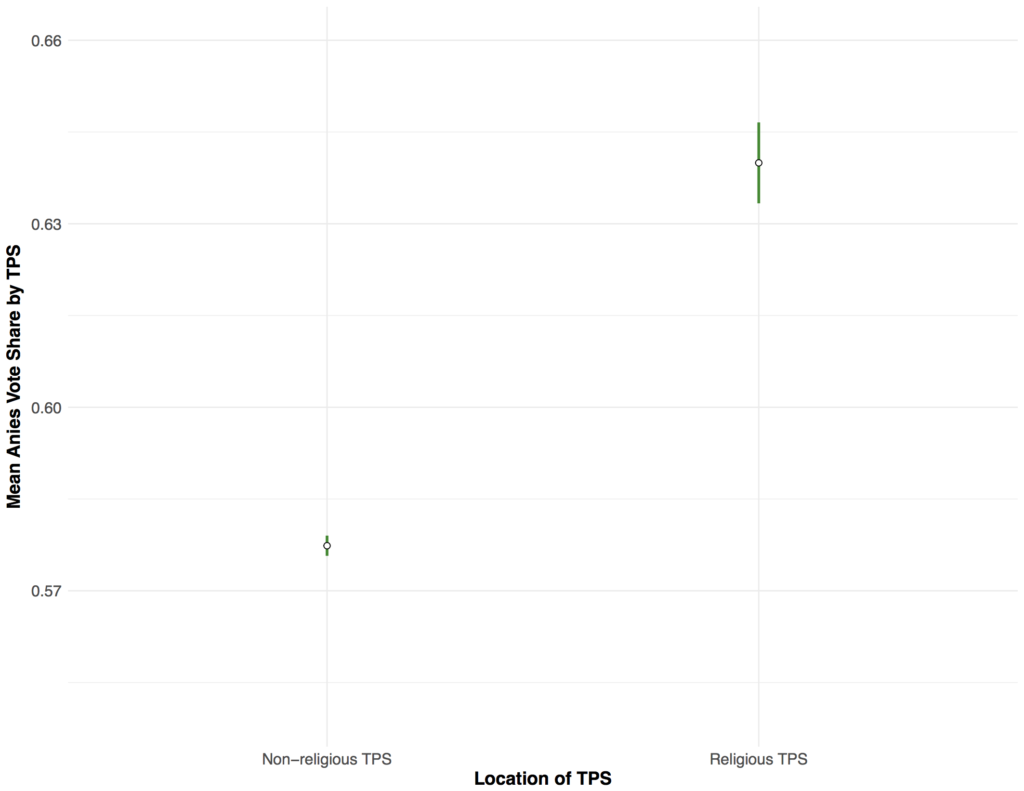

I combined the 2017 gubernatorial election results with a separate document that lists the location of voting stations. As one might expect, figure one (below) shows that voting stations housed in mosques or mushollas exhibited much higher rates of support for Anies (64%) than those housed in non-religious places of worship (57%). Voting stations in and around mosques and mushollas, on average, showed a 6-percentage-point increase for Anies.

Figure #2 (below) breaks the finding into more detail and shows the relative distribution of votes based on the location of the voting station. Two interesting things emerge from this plot. Voting in mosques and mushollas appears to have pushed the distribution to the right, thereby favouring Anies. But the distribution of vote shares is also much more tightly clustered in voting booths housed in mosques and mushollas.

To be sure, there is good reason to be sceptical about a straightforward interpretation of this finding. For one, it is purely correlational. The neighbourhood-level election commission, composed of community members, selects the location of the TPS. It might be the case that neighbourhoods that are more religious both vote for Anies at higher rates and tend to select religious establishments as their voting stations.

It could also be that the correlation between TPS location and Anies’ vote share is really just picking up socioeconomic factors. It might be the case that poorer communities disproportionately select mosques and mushollas as their polling stations given the absence of other suitable venues, like schools and badminton courts. And, as Ian Wilson has pointed out, poorer communities were often sites of intense animosity towards Ahok, as they bore the brunt of many of his urban development programs (in addition to broader ethnic and religious factors).

But the possibility that voting in religious establishments shapes voting behaviour is a serious concern. If Indonesia’s electoral authorities are to take seriously Jusuf Kalla’s recommendation that places of worship should not be politicised, they might start with the literal separation of voting from religion.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss