When Indonesia’s New Order regime met its end in May 1998, I was a PhD student researching Indonesian opposition movements while teaching Indonesian language and politics at a university in Sydney. Along with other lecturers and students, I watched the live broadcast of Suharto’s resignation speech, listening to the words of one of our colleagues as she translated the president’s fateful words for Australian TV. Clustered around a television screen in a poky AV lab, everyone present felt awed by the immensity of what we were witnessing, relieved that a dangerous political impasse had been broken, and nervously hopeful about the future after so many long years of political stagnation.

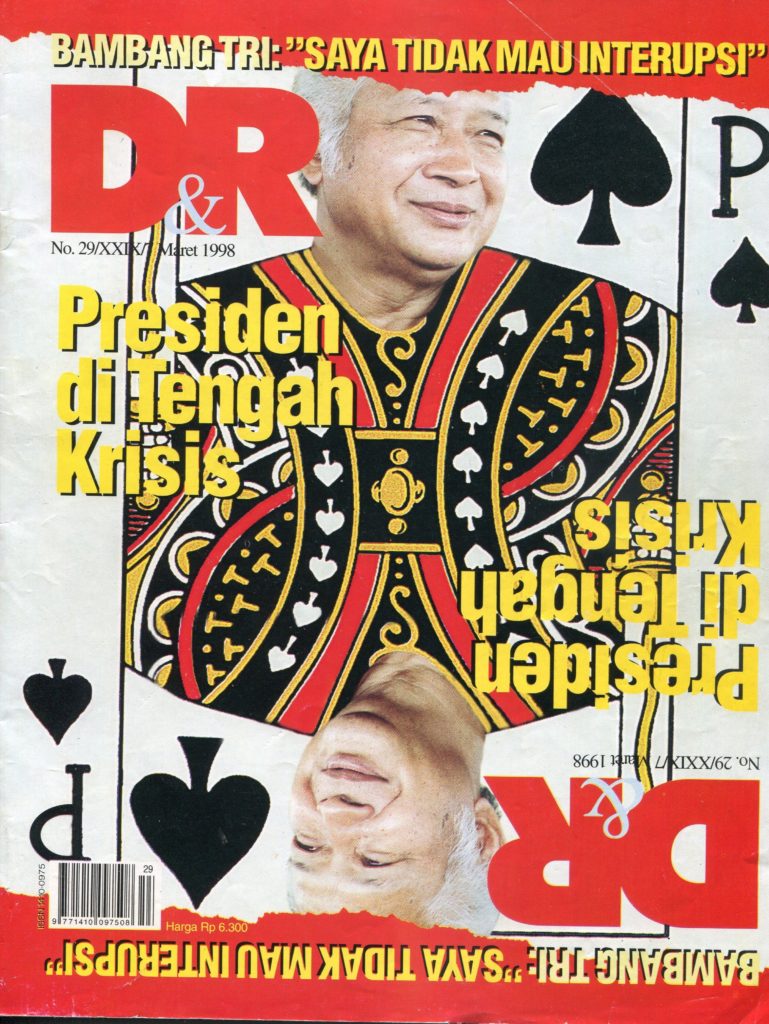

This March 1999 cover of the Detektif dan Romantika magazine, rendering Suharto as the Ace of Spades, was a striking sign of his regime’s crumbling legitimacy in its final months, and a major marker of the media’s growing willingness to criticise the president openly. D&R was a major source of critical reporting in the regime’s final years, after it became a refuge for journalists who had lost their jobs when Tempo magazine was banned in 1994. (Photo: author)

The extraordinary achievements of political reform in the years that followed formed one of the great success stories of the so-called “third wave” of democratisation—the worldwide surge of regime change that began in Southern Europe in the mid-1970s and then spread through Latin America, Africa and Asia. The post-Suharto democracy has now lasted longer than did Indonesia’s earlier period of parliamentary democracy (1950–1957), and the subsequent Guided Democracy regime (1957–65). While it still has another dozen years to pass the record set by Suharto’s New Order, Indonesian democracy has proved that it has staying power.

What few would question, though, is that the quality of Indonesia’s democracy was a problem from the beginning—and that under President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) democratic quality has begun to slide dramatically.

Earlier this year, the Economist Intelligence Unit gave Indonesia its largest downgrading in its Democracy Index since scoring began in 2006. With a score of 6.39 out of a possible maximum of 10, the country is now bumping down toward the bottom of the index’s category of “flawed democracies”, on the verge—if it sinks just a little lower—of crossing into the category of “hybrid regime”. This downgrading of Indonesia’s position follows similar drops for the country in other democracy indices like the Freedom in the World survey compiled by Freedom House.

Indonesia’s trajectory is not bucking the global trend. Around the world, democracy is in retreat. Freedom House says democracy is facing “its most serious crisis in decades”, with 71 countries experiencing declines in political rights and civil liberties in 2017 and only 35 registering gains, making 2017 the twelfth year in a row showing global democratic recession.

Unlike during an earlier era of military coups, today the primary source of democratic backsliding is elected politicians. Leaders such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán undermine the rule of law, manipulate institutions for their own political advantage, and restrict the space for democratic opposition. Elected despotism is, increasingly, the order of the day. Indeed, as I argue here, the primary threat to Indonesia’s democratic system today comes not from actors outside the arena of formal politics, like the military or Islamic extremists, but the politicians that Indonesians themselves have chosen.

Eroding democracy, in democracy’s name

Over recent years, successive central governments have introduced restrictions on democratic rights and freedoms in Indonesia. This process began during the second term of the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency, which began in 2009, but has accelerated significantly since the election of Jokowi in 2014.

The immediate backdrop to some of the most regressive moves has been the contest between Jokowi and his Islamist and other detractors, especially in the wake of the mobilisations against the Chinese Christian governor of Jakarta, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok).

In July 2017, Jokowi issued a new regulation, subsequently approved by the national legislature, that granted the authorities sweeping powers to outlaw social organisations that they deemed a threat to the national ideology of Pancasila. The new law actually built on an earlier, somewhat less harmful version issued during the Yudhoyono presidency. The government quickly took advantage of the law to outlaw Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia, a large Islamist organisation that, while openly rejecting pluralism and democracy, has also pursued its goals non-violently.

At the same time, several critics of President Jokowi have been arrested on charges of makar, or rebellion (though it appears the authorities may not be proceeding with these cases). The government has coercively intervened in the internal affairs of Indonesia’s political parties so as to attain a majority in parliament. A prominent media mogul supportive of anti-Jokowi political causes was slapped with what appeared to many to be politically-motivated criminal investigations. Foreign NGOs and funding agencies face an increasingly restrictive operating climate.

Meanwhile, the military has been brought back into governance, at least at the lowest levels of the state, with the government reinstituting the Suharto-era of babinsa—junior officers assigned to villages—and promoting military involvement in non-security related functions as fertiliser distribution.

A related source of decline in the quality of Indonesia’s democracy, meanwhile, is intolerant attitudes toward religious and other social minorities, alongside narrowing public space for critical discussion of religious topics, and the growing ascendancy of religious conservatism in social and political life.

Anti-Ahok protests in Jakarta, December 2016 (Photo: Abraham Athemius on Flickr, Creative Commons)

A few years ago, religious minorities such as Shia Muslims and members of the Ahmadiyah sect were the most frequent target of violent attack and restrictions; recently, the country has been gripped by an anti-LGBT panic. It is possible that Indonesia will soon criminalise homosexuality. At a time when many third-wave democracies, notably those in Latin America, are becoming more respectful of the rights of homosexuals and other sexual minorities, Indonesia is moving in the opposite direction.

While none of these government measures has in itself been a knockout blow against freedom of expression and association, taken together they constitute a significant erosion of democratic space. As the global democracy indices recognise, it already makes no sense to speak of Indonesia as being a full, or liberal, democracy. These developments point toward, at best, Indonesia’s becoming an increasingly illiberal democracy, where electoral contestation continues as a foundation of the polity, but coexists with significant restrictions on political and religious freedoms, and where the rights of at least some minority groups are not protected.

Defying the odds

But the picture is not unremittingly gloomy. Indonesia has a long way to go before it sinks to the level of Russia or even Turkey, and it is worth pausing to contextualise the recent trends in the context of the achievements of Indonesian democracy over the last 20 years.

Many of these gains remain firmly established. Democratic electoral competition has become an essential part of Indonesia’s political architecture. Apart from sporadic calls to do away with direct elections of regional heads (pilkada), no mainstream political force calls openly for electoral mechanisms to be replaced with a rival organising principle. Even when the authoritarian populist Prabowo Subianto ran for the presidency in 2014, he had to disguise his anti-democratic impulses with talk of returning to Indonesia’s original 1945 Constitution—i.e. the version of the constitution that the Suharto regime had relied upon, but which seems attractive to many Indonesians because it resonates with Indonesia’s nationalist history.

Public opinion surveys demonstrate continuing strong support both for democracy as an ideal, and for the democratic system actually practised in Indonesia. Moreover, Indonesia still has a relatively robust civil society and independent media, at least in the major cities. Political debate on most topics remains lively. For example, it is generally easy for critics of President Jokowi to express their views loudly and directly—not something that can be done in most of Indonesia’s ASEAN neighbours. Indeed, some of the recent attempts to curtail free speech has been prompted by concerns about the ease with which so-called “fake news”, conspiracy theories and wild rumours circulate through social media.

Moreover, it is worth emphasising that many of the very people who pose the greatest threat to Indonesian democracy—its elites—have in fact bought into the new system. Elites throughout the country have benefited from the new opportunities for social mobility and material accumulation they have been able to secure through elections and decentralisation.

A recent survey of members of provincial parliaments, conducted by Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI) in cooperation with the Australian National University, shows that while Indonesia’s regional political elites are certainly illiberal on many issues, they are strongly supportive of electoral democracy as a system of government. Indeed, on many questions their views are markedly more democratic than the general population.

For example, when asked to judge on a 10-point scale whether democracy was a suitable system of government for Indonesia, the average score provided by these parliamentarians was 8.14—not far from the maximum score of 10 for “absolutely suitable”, and a full point higher than the 7.14 given by respondents in LSI’s most recent general population survey in which the same question was asked. Likewise, these legislators were considerably less likely to support military rule or rule by a strong leader than were the population at large.

These responses are significant, because democracy is not simply a system favouring protection of civil liberties and ensuring accountability of officials to the public (areas where Indonesia has, to spin it positively, a mixed record). It is also a means of ensuring regular and open competition between rival political elites.

Viewed in this light—as a means of regulating elite circulation—Indonesian democracy looks more robust. Though elite buy-in does not preclude continuing erosion of civil liberties at the centre, or guarantee protection of unpopular minorities, it does pose a considerable obstacle to the return of a command-system of centralised authority such as that which ruled Indonesia under the New Order.

A consolidated low-quality democracy?

It is in no small part due to this elite support for the status quo—in part begrudging and contingent, but nevertheless real—that Indonesian democracy has proven resilient to potential spoilers. This resilience is in itself an important achievement: there is a body of scholarly literature that suggests that once a country has experienced democratic rule for a lengthy period—one scholar, Milan Svolik, puts the figure at 17–20 years—it is very unlikely to regress toward outright authoritarianism.

Moreover, Indonesia’s present backsliding—as with the wider global trend—can arguably be viewed in part as a retreat that comes after a democratic high water mark is reached. If the last century is any guide, democratic progress and regression come in worldwide waves: the third wave of democratisation which began in the 1970s was preceded by two earlier waves that came in the wake of World War I and World War II. In both periods, many of the newly democratic regimes that were established in the wake of the breakup of multinational and colonial empires did not last long. But in each case, these retreats were superseded by new waves of democratisation.

Jokowi conducting a ‘blusukan’ while governor of Jakarta (Photo: Pemprov DKI Jakarta)

Obviously, we need to be cautious when thinking about future trends. We are in the midst of a new world-historic transition and we do not know whether we are merely at the start of the worldwide retreat of democracy, or already near the turning of the authoritarian tide.

Most worryingly, some of the ingredients giving rise to democratic weakening in the current period are new, and do not yet show signs of abating. Strikingly, for the first time in decades, there are signs of weakness in advanced democracies—both in terms of declining popular support for democracy as measured in some opinion polls, and in the election of would-be autocrats such as Donald Trump. Wealth inequality in many countries is reaching levels not seen since the dawn of the age of mass democracy a century ago, with the result that the growing political dominance of oligarchs—a major focus of academic analysis in Indonesia—is a worldwide trend. Meanwhile, new communication technologies of the internet and social media are opening up participation in political debate, but also driving a polarisation that undermines a shared public sphere and delegitimises opponents.

Behind Indonesia’s illiberal turn

Oligarchs have weaponised identity politics in their struggles over power and resources. That means it's not going away any time soon.

Nevertheless, it is worth viewing contemporary predicaments from the perspective of those of us who watched Suharto resign 20 years ago. Back then, as we watched Suharto read out his speech, my friends and I mixed astonishment, excitement and relief with genuine anxiety about what was in store for Indonesia. Many expert commentators were very sceptical of the notion that Indonesia could become a successful democracy. Some urged caution, pointing to the acrimony that had dogged Indonesia’s earlier democratic experiment in the 1950s, and highlighting the under-development of civilian politics and the continuing influence of the armed forces.

Indonesian democracy exceeded most expectations back then. It might just do so again.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss